Inspired by Jack Traynor’s 1987 paper, ‘Market Efficiency and the Bean Jar Experiment’, Michael Mauboussin, an adjunct professor of finance at Columbia Business School, repeats the same experiment annually.

A large group of students are asked to individually guess the number of jelly beans contained in a sealed jar. Unsurprisingly, individual guesses are far off the mark, but their collective average is always remarkably accurate. The median guess of the group is within 1% of the actual number of beans in the jar.

This is known as the Paradox of Collective Wisdom.

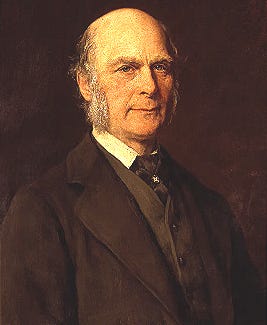

The phenomenon is nothing new. In 1907, Charles Darwin’s cousin, a polymath named Francis Galton, attended an agricultural fair in Plymouth, England. He analyzed 787 entries in a contest to guess the weight of an ox after slaughter. While individual guesses varied widely, their central tendency converged on the correct answer. He discovered that the median estimate of 1,207 pounds was remarkably close to the actual weight of 1,198 pounds, with an error of less than 1%.

Galton’s idea has recently been popularized in a book by James Surowiecki, entitled the ‘Wisdom of Crowds’. The observation made is, generally, that under the right circumstances, groups are capable of achieving far better results than any member of the group is capable of achieving alone.

This seems to validate the fundamental premise of Eugene Fama’s efficient market hypothesis, which postulates that markets, representing the aggregate wisdom of many participants, should efficiently price assets to reflect all available information.

Yet reality presents us with a puzzling contradiction: financial markets regularly experience dramatic boom and bust cycles that appear to defy both efficiency and collective wisdom.

How can this be explained? What does it tell us?

The Wisdom of Crowds: Why It Works

The jelly bean experiment succeeds because it satisfies several crucial conditions for collective wisdom to emerge. First, the estimates are made independently, without participants influencing each other. Second, the question has an objective, unchanging answer. Third, participants have some basis for making an informed guess - they can see the jar and draw upon their mathematical and logical experience. Finally, individual errors tend to be randomly distributed around the true value, allowing overestimates and underestimates to cancel each other out.

Markets: A Different Beast

Financial markets, however, operate under fundamentally different conditions that can undermine collective wisdom:

1. Interdependence: Unlike independent jelly bean guessers, market participants constantly observe and react to each other's behavior. This creates feedback loops where rising prices attract more buyers, pushing prices even higher, regardless of fundamental value.

2. Moving Targets: While a jar contains a fixed number of jelly beans, the true value of financial assets depends on future earnings, interest rates, and other variables that constantly change and are inherently uncertain.

3. Psychological Factors: Markets are driven by human psychology, including fear, greed, and cognitive biases. When these emotions spread through the market, they can create self-reinforcing cycles that drive prices far from rational levels.

The Efficient Market Paradox

The efficient market hypothesis postulates that asset prices reflect all available information because any mispricing would be quickly identified and corrected by rational investors seeking profit opportunities. This theory, like the wisdom of crowds, assumes that individual errors in judgment will cancel out, leaving prices at efficient levels.

However, this overlooks several critical factors:

1. Limits to Arbitrage: Even when sophisticated investors identify mispricing, various constraints - including transaction costs, short-selling restrictions, and career risk - may prevent them from trading aggressively enough to correct it.

2. Rational Bubbles: In some cases, it may be rational for investors to participate in a bubble while it's inflating, chasing momentum rather than fair value, even if they recognize asset prices as excessive. As long as they believe they can sell to someone else at a higher price (the "greater fool" theory), the bubble can persist.

3. Collective Irrationality: Historical episodes like the Dutch tulip mania, the South Sea bubble, and more recent events like the dot-com bubble demonstrate how markets can become detached from reality.

Reconciling the Contradiction

The paradox between jelly bean wisdom and market inefficiency suggests that collective wisdom is context-dependent. When conditions support independent judgment and objective truth-seeking, crowds can display remarkable accuracy. But when social influence, emotion, and uncertainty dominate, the same mechanisms that produce wisdom can instead amplify errors and create systematic biases.

“While crowds can be wise under the right conditions, they can also exhibit collective madness. Paradoxically, the way to achieve the best result from a group is for each of its members to think and act independently.”

James Emanuel

This understanding points toward a more nuanced view of market efficiency. Markets may be relatively efficient most of the time, incorporating available information into prices through the aggregation of diverse views. However, they are also subject to periods of collective dysfunction when the conditions for wisdom break down.

Implications and Lessons

This analysis carries an important lesson for investors. Markets should not be viewed as infallible price-setting mechanisms but as complex adaptive systems that can alternate between periods of efficiency and inefficiency.

The paradox of collective wisdom in markets reminds us that simple principles, however powerful, often require careful qualification when applied to complex social systems.

The key challenge is recognizing when the market is behaving irrationally and determining whether this presents an investment opportunity - such as an undervalued security - or a risk, like an unsustainable bubble which is best avoided.