Haunted by Valuing Programmatic Acquirers?

It's Harder Than It Looks, Easier Than You Think, Just Poorly Understood

Why does a company look good on paper, but turn out to be a poor investment?

Why do conventional valuation metrics invariably sign-post the wrong companies?

Are corporate accounts a work of fact or fiction?

With so much goodwill, how and where did it all go so wrong?

Struggle To Value Programmatic Acquirers?

There’s a profound disconnect between accounting treatment and economic reality for programmatic acquirers. Investors who grasp the nuances of these unusual businesses are far better positioned to identify which acquirers will deliver superior returns.

Companies that look “expensive” on traditional metrics, such as high earnings multiples, may actually be deeply undervalued if they are able to compound their economic goodwill (defined later). Meanwhile, companies that look “cheap” may prove to be costly if they’re capital-intensive with little or no such value creating opportunity.

Confused? You’re not alone. Most investors tie themselves in knots over this.

The good news? It’s not rocket science. If I can understand it, you can too.

Programmatic Acquirers Confuse Analysts

Programmatic acquirers like Constellation Software compound at extraordinary rates (37% annually over 19 years), while appearing expensive or confusing to traditional analysts.

Why?

The accounting profession’s treatment of goodwill systematically obscures what makes these businesses valuable: the aggregation and appreciation of economic goodwill across a diversified portfolio of high-return businesses.

Let’s not forget, statutory accounting requirements weren’t designed to aid investment decisions. They are primarily a means of quantifying the performance of a business for the tax man. This leads to creative accounting designed to mitigate tax liabilities and, when combined with numerous estimates - depreciation schedules, bad debt provisions, inventory valuations, fair value measurements and asset impairments, statutory accounts become more a work of fiction than a record of fact.

“There is no question, the leeway I have to report earnings as CEO of Berkshire is enormous.” - Warren Buffett

The truth is that corporate accounts, in raw form, offer little value to investors and can be entirely misleading. I won’t labour the point, but if you would like to learn more, I highly commend the book “The End of Accounting and the Path Forward for Investors” by two eminent American university professors, Baruch Lev and Feng Gu.

So where does that leave us, particularly when assessing programmatic acquirers?

Everything turns on the very poorly implemented concept of Goodwill. The issue is that accountants use this term to describe a fiction and, in so doing, ignore the type of goodwill that’s undeniably real.

I’ve used the term ‘economic goodwill’ a few times so far, now I’ll define it:

Accounting Goodwill = the excess of the cost of an acquired company over the fair value of its identifiable net assets

Economic Goodwill = the real value of the non-maintainable intangible assets, such as brand and reputation, that generate revenue and so create corporate value

These two are related, but fundamentally different. In fact, they’ll be equal at the point in time that an acquisition is made - but at all other times they diverge, and therein lies the problem.

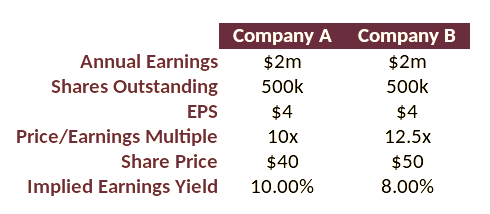

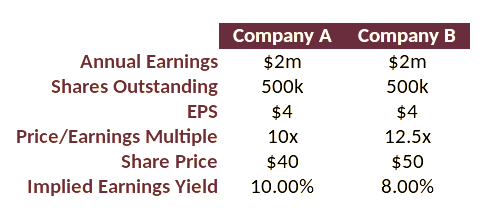

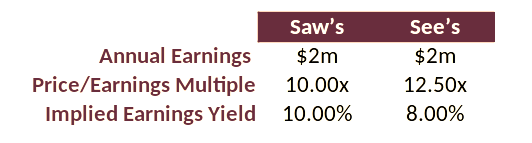

Before we dive deeper, a quick test for you. Given the information in the table below, which company would you invest in?

Read on, and let’s see if you change your mind. I bet you will.

What A Mess The Accountants Made!

The accounting treatment of Accounting Goodwill has changed dramatically over the years, and not for the better.

Early Days: Accountants didn’t recognize Goodwill as an asset at all. It was expensed immediately, causing earnings turbulence with huge extraordinary expenses that disappeared the year after acquisition.

1969: Goodwill was capitalized and amortized over an arbitrary 40 years. Arbitrary because predicting the useful life of Goodwill or how its value changes over time is impossible. Straight-line amortization over a fixed period makes no economic sense.

1980s: The profession began to question the logic of amortization again. After all, Goodwill doesn’t necessarily erode and doesn’t need to be replaced.

1993: After a decade of debate, the rules changed: Goodwill could be carried indefinitely instead of being amortized and would be tested annually for impairment.

Under impairment testing, if Goodwill was subjectively deemed worth less than book value (opening the door to managerial interpretation and bias), the negative difference became an impairment cost on the income statement, with the asset written down on the balance sheet.

This methodology was not only subjective and unreliable but also untimely. Goodwill erosion is never evident until well after the fact, meaning impairment costs were recorded in the wrong period, creating a misleading picture of business activity.

The profession effectively replaced one arbitrary approach with another. A new complex impairment methodology was introduced with disclosure obligations aimed at transparency, but this merely added cost and complexity.

Now, the accountants are discussing the reintroduction of amortization of Goodwill, so they’ve gone full circle. What a mess!

All the while, they fail to recognize the most important aspect of Goodwill from an investor’s perspective:

The Goodwill of a strong company doesn’t erode in value at all. Economic Goodwill increases in value and that is the magic ingredient to very favourable investment returns - the secret sauce of programmatic acquirers. This is more relevant then ever in times of high inflation (just like today!)

So, let the accountants tie themselves in knots. We don’t care. We simply need to navigate through their mess and we’ll be just fine.

Breaking It All Down, One Step At A Time

Assume a company, SuperCo, has $20 per share of net tangible assets. Further assume that this is a strong business with a moat that is able to earn a great deal on its tangible assets, say $5 per share (25% return).

With such economics, an investor might capitalize the business at 20x earnings, valuing it at $100 per share.

Now imagine you bought a majority stake in SuperCo at $100 per share, the accounting goodwill (the premium above net tangible value) is $80 per share ($100 - $20). The economic goodwill happens to be the same at that point in time.

But now consider these questions:

If the company continues generating $5 per share of earnings indefinitely, is your Goodwill eroding? No. All else equal, it remains the same.

What happens if sometime later you buy more shares, but now at $120 each? The business still has $20 per share of net tangible assets and continues to generate $5 per share of earnings. Accountants will book the accounting goodwill element at $100 per share ($100 - $20), despite the exact same asset already sitting on your balance sheet with accounting goodwill valued at $80. In other words, different purchase dates and share prices have given us vastly different asset values for two pieces of the same asset! How can that be?

Let’s take this a step further and assume that SuperCo doubles in size. Tangible assets increase to $40 per share and earnings double to $10 per share. If the company uses $20 per share of debt to increase its tangible asset base and is still capitalized at 20x earnings net of debt, the economic value of the business becomes $180 per share ((20 x $10) - $20). Now ask yourself, what’s the true “economic goodwill” now? For your initial $100 purchase, goodwill has increased from $80 to $140 per share ($180 - $40). None of this appears in corporate accounts on the balance sheet, but it’s very real to you as an investor.

If you sold the business to someone else at this new valuation, they would record $140 of accounting goodwill (remember that economic goodwill and accounting goodwill come into equilibrium at the point of an acquisition), but on your balance sheet it still appears as $80 (because, absent an acquisition, accounting goodwill doesn’t kept pace with reality and is no longer in equilibrium with economic goodwill). Same asset - vastly different valuation. The true economics aren’t captured on the balance sheet.

It would be even worse under the amortization model that accountants are threatening to bring back! Let’s return to the original example, we pay 20x earnings of $5 per share, with net assets of $20 per share so goodwill is recorded at $80 per share. If this is amortized at $2 per share annually for 40 years, that would appear as a cost on the income statement. So net earnings reduce from $5 per share to only $3 per share, which at a 20x multiple implies the shares are now worth only $60 rather than the $100 we paid, or that we paid an eye-watering 33x earnings. Did we overpay? Or are accountants misguiding us? I’ll leave you to decide.

Non-Cash Acquisitions

The situation becomes more complex when a business acquires another for stock rather than cash.

When a company’s market capitalization changes, it’s not the tangible assets that change, it’s the economic goodwill. The premium over tangible assets that the market is prepared to pay for the business.

When a company uses its own shares to purchase another business, it’s essentially embarking on a Goodwill swap. When a company’s stock trades at very high multiples, meaning its Goodwill is overvalued, using that inflated currency to acquire better-valued assets makes excellent sense.

By way of example, say your business trades at 40x earnings when 20x is more appropriate, swapping your shares for those of another fairly valued company means you’re effectively acquiring its economic goodwill at a 50% discount. You could achieve the same by selling your shares and using the proceeds of sale to buy the other company’s shares, but that cash transaction would attract tax - a share swap avoids that liability.

This is exactly what Henry Singleton and Warren Buffett have done on many occasions (click here to learn more).

It doesn’t end there. If you acquired shares in the other company at a 50% discount - imagine that the other company had identical unit economics to yours and you exchange one of your $100 shares for two of its $50 shares - because no cash changed hands, the accounting goodwill on your balance sheet remains unchanged at $80. But, you’ve effectively acquired its shares for $50, less $20 of tangible assets, which means that in respect of the swapped shares the economic goodwill is $30 per share.

The balance sheet is even more out of shape than ever at this stage of proceedings!

The Goodwill Disappearing Trick

Let’s consider The Coca-Cola Company as a wonderful case study in the context of today’s accounting rules.

The Coca-Cola Company developed its beloved drink recipe, in-house, in 1886. Because the recipe was created internally, accountants are required to expense 100% of that R&D immediately. It’s a big cost hit to the income statement in the year of development but since it’s not a capitalized expense, no asset is recognized on the balance sheet.

Accountants don’t see the recipe as an asset!

Is the recipe not Coca-Cola’s most important asset?

Is it not still making money from that recipe today, 150 years later?

Not only does the asset exist, the company is actually making far more money from that recipe now than in the early years, so this intangible asset has significantly increased in value. The economic goodwill of the business has sky-rocketed in value, but ‘Abracadabra’, just like magic, the accounting goodwill has completely disappeared. Go figure!

Those talented accountants are also able to make it re-appear, but only if The Coca-Cola Company is acquired. In those circumstances, ‘hey presto’, goodwill would materialize on the balance sheet of the acquirer.

Seen from another angle, if everything else stayed the same but Coca-Cola’s ownership changed, its return on assets and return on equity would plummet. The reason is simple: the balance sheet doesn’t reflect the company’s most valuable asset, but that would change with the ownership.

Does this accounting alchemy make any sense to you?

In truth, the economic goodwill has been there all along, hiding in plain sight. The asset doesn’t miraculously materialize simply because the company is acquired.

Warren Buffett and other programmatic acquirers understand this implicitly:

“The premium we pay above the net assets recorded on the books of the predecessor company overwhelmingly is for what we call economic goodwill. We don’t even look at the plants. We did not look at the plants of Scott Fetzer before we bought it. We did not look at the plants of H.H. Brown before we bought it. I have not looked at the plants since, I have never seen the plants at H.H. Brown. We don’t think in terms of appraising physical assets. We think in terms of economic goodwill.”

Warren Buffett

Even when accountants recognize intangible assets on the balance sheet, the approach to recording them distorts reality. If Coca-Cola had acquired the recipe from someone else for the same cost it incurred in R&D, it would have been recognized as an intangible asset and amortized over 15 years. The same company with the same recipe at the same cost would be treated in two irreconcilable ways by accountants.

The cost, although the same both ways, would either be recognized in the year it was incurred as R&D, or else amortized on a straight-line basis over 15 years if acquired from a third-party. The only consistency? After 15 years, the asset disappears entirely. The income statement would look completely different over those 15 years, despite the cash flows being identical. Equally ridiculous.

Of course, we as investors recognize economic goodwill regardless of the accountancy profession’s madness. This manifests in the difference between Coca-Cola’s market capitalization and its net tangible assets value. The big challenge is in reconciling fact with the fiction of the corporate accounts. This explains why commonly used metrics, including earnings multiples, book value multiples and returns on assets, equity and capital so often create misleading signals.

Beware Programmatic Acquirers Juicing Earnings

Ironically, while much of the discussion around goodwill focuses on accountants concealing it, some programmatic acquirers do quite the opposite. After an acquisition, they allocate too much of the purchase price to goodwill, deliberately. It’s a subtle form of financial engineering.

Instead of conducting a proper, line-by-line purchase price allocation (as best practice dictates), a disproportionate share of the acquisition cost is lumped into goodwill. Why? Because goodwill isn’t depreciated, it’s only subject to periodic impairment testing. That means lower depreciation and amortization expenses in operating costs, which conveniently boosts reported earnings.

Higher earnings often lead to higher share prices, and when executive pay is tied to those share prices, the incentives start to look very questionable. It’s a classic case of short-term optics trumping long-term integrity.

This kind of behaviour is problematic on several fronts. It misleads investors, it’s poor governance and it’s even tax-inefficient: you’re effectively reducing tax-deductible depreciation expenses in exchange for cosmetic accounting gains. Worse still, it can set up a valuation trap. When expected growth or synergies from acquisitions fail to materialize, that inflated goodwill suddenly turns into a write-down, slashing reported earnings and triggering a sharp re-rating of the share price.

During the ZIRP era, when interest rates were near zero, it was easy to justify rosy assumptions. But with rates now normalized, impairment tests have become far stricter, leaving aggressive goodwill allocators more exposed than ever.

Who wants that risk?

Constellation Software and its spin-offs, Topicus and Lumine, show how it should be done. They allocate acquisition costs properly, line by line, and typically less than 20% ends up in goodwill. That discipline reflects both transparency and the group’s knack for acquiring quality businesses at sensible valuations, without paying too much of a premium over the net asset value of the target company.

Lifco, the highly successful Scandinavian acquirer, takes a different approach. It often pays premium prices for targets sourced through brokers and auctions, where competition pushes valuations up. Unsurprisingly, its goodwill allocation sits closer to 60%.

At the other end of the spectrum, some smaller acquirers - often eager to prove themselves - have been known to allocate nearly 100% of the purchase price to goodwill. It’s hard to understand how auditors sign off on this, but it happens. So, beware.

The lesson is simple: invest in the right kind of management team: one that’s honest, transparent and doesn’t play games with the numbers. Goodwill allocations are an excellent way to spot red flags when assessing a programmatic acquirer.

Value the Captain of the Ship

On the subject of invisible assets and quality management, how many investors actually assign value to the CEO?

My view has always been that people are the most important part of any enterprise. Consider Apple under John Sculley versus Steve Jobs: same company, same industry, same customers, yet completely different outcomes.

When you’re evaluating programmatic acquirers, management quality is everything. Don’t invest in a business simply because it’s growing by acquisition. The “Acquisition-as-a-Business” model only works when the people running it are exceptional capital allocators.

In truth, most companies are run or guided by chartered accountants serving as the CEO or CFO and, as we’ve discussed, accountants often see the world through a very different lens than investors. That’s one reason so many firms misfire when it comes to acquisitions.

The lesson: If you invest in the wrong management team, don’t expect wonderful returns.

The great acquirers think like investors, not accountants. Warren Buffett, Mark Leonard, and Jeff Bezos are prime exemplars, each with roots in the investment world:

Jeff Bezos, before founding Amazon, worked at D. E. Shaw on Wall Street and went on to make more than 130 acquisitions.

Mark Leonard, before building Constellation Software, worked at Ventures West, a Canadian venture capital firm and has since successfully acquired over 900 businesses.

Warren Buffett began as a securities analyst and investment salesman before becoming Berkshire Hathaway’s CEO, acquiring or investing in hundreds of companies along the way.

Is it really a coincidence that these master capital allocators all came from investment backgrounds? I think not.

Most investors pore over the quantitative data when running side-by-side comparisons of different programmatic acquirers, yet few give equal weight to the qualitative elements: the integrity, competence and career history of the person steering the ship.

Perhaps this is something for you to consider before making your next investment.

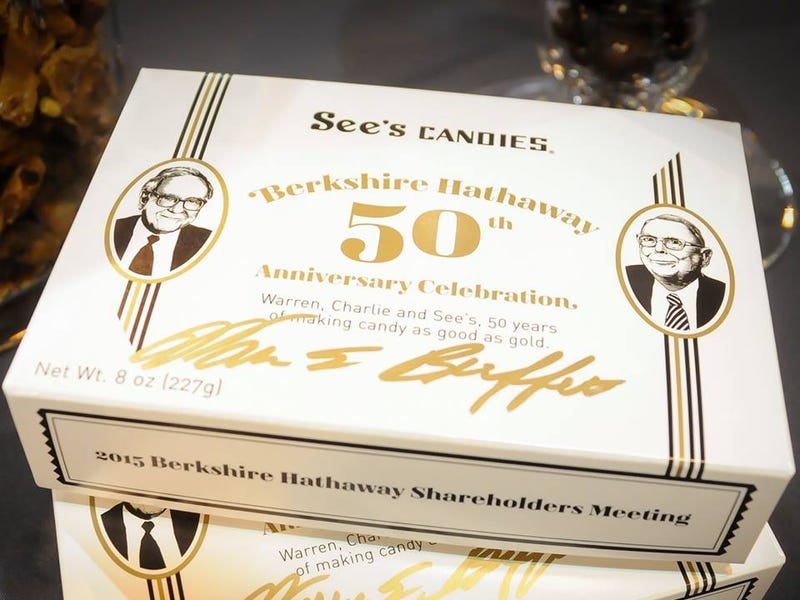

A Real Case Study: See’s Candy

In 1972, Berkshire Hathaway bought a business called See’s Candy. It had about $8 million of net tangible assets (including working capital). This level of tangible assets was adequate to conduct business without debt, and See’s was earning about $2 million after tax. Buffett paid $25 million, so 12.5x net earnings.

Earning $2 on $8 of net tangible assets (25% return) is something few businesses are able to consistently achieve, especially without financial leverage. It wasn’t the fair market value of inventories, receivables or fixed assets producing premium returns, it was intangible assets: a wonderful brand and many loyal, satisfied customers. This is what Buffett calls a consumer franchise, a prime source of economic goodwill.

Buffett paid $17 million over net tangible assets for See’s, recorded as goodwill on the balance sheet.

More specifically, $425,000 was charged to the income statement annually for 40 years to amortize that asset (the arbitrary accounting rule at the time).

By 1983, after 11 years of such charges, the $17 million of Goodwill had been amortized down to about $12.3 million. Yet by this time, See’s was earning $13 million after taxes on about $20 million of net tangible assets (65% return). If capitalized at the same 12.5x earnings multiple, it was worth $162.5 million (+550% in 11 years). The economic goodwill had increased, not decreased. Despite the accounting goodwill showing at $12.3 million on the balance sheet, it was actually worth closer to $142.5 million.

“We only buy it if we think [goodwill] is going to appreciate.” - Warren Buffett

Given that the returns on net tangible capital had increased from a great 25% to an outstanding 65%, it would have experienced multiple expansion and so the true economic goodwill would have been higher still.

So, in the absence of a business melt-down, economic goodwill goes up, while accounting goodwill remains static or declines (depending on whether accountants use the impairment vs amortization model).

Even if the business had failed to grow, Goodwill would increase in value simply due to inflation.

Inflationary Environments

Remember Buffett acquired See’s Candy when it was earning about $2 million on $8 million of net tangible assets. Buffett paid $25 million (12.5x earnings, an 8% earnings yield).

Assume another company, Saw’s Candy, also generated $2 million of earnings but on $20 million in net tangible assets. This company might only be worth its net tangible assets, $20 million (10x earnings, a 10% earnings yield), because its growth prospects are less favorable than See’s.

So, at the time of acquisition, See’s has $17 million in goodwill while Saw’s has zero.

Now imagine inflation is running at 100% - everything doubles. Both See’s and Saw’s need to double earnings to $4 million just to keep pace with inflation (flat in real terms). To achieve this, they sell the same number of products at double the price.

But to make this happen, net tangible assets, including working capital (receivables, inventory) must also double. Maintenance capex responds the same way to inflation: it doubles.

See’s needs to raise $8 million of new capital; Saw’s needs $20 million. Which business would you rather own?

Crucially, all this capital investment forced by inflation produces no improvement in the rate of return. The motivation is business survival.

Assuming both raise the requisite capital, Saw’s now has $40 million of net tangible assets earning $4 million annually. Remaining more capital-intensive than See’s, it continues trading at 10x earnings, worth $40 million (zero goodwill). It has essentially raised $20 million of new capital to increase market capitalization by $20 million. Shareholders gained only a dollar of nominal value for every new dollar invested.

By contrast, See’s, which now also earns $4 million, might be worth $50 million if valued at 12.5x earnings as it was at the time of Buffett’s purchase. But Buffett paid $25 million, so it gained $25 million in nominal value while owners put up only $8 million in additional capital: that’s over $3 of nominal value gained for each $1 invested.

Now you know why Buffett acquired it - it passes the Berkshire Hathaway test: $1 of shareholder capital reinvested must generate a handsome return on that investment.

Saw’s started with zero economic goodwill and ended with zero. See’s started with $17 million in economic goodwill and ended with $34 million.

Through another lens: if Saw’s could only match the $8 million of capital See’s raised, it would have grown 40% versus 100% growth at See’s.

Now you see why See’s is far more desirable and why investors pay more to own it. This is why it trades at a higher earnings multiple.

The Test Results

Remember the test at the beginning of this post?

Did you choose Company A or Company B?

Let’s explore the answer.

While you’d need more information for an informed investment decision, there’s much implied in what you have. Most amateur investors immediately favour the stock trading at the lower earnings multiple: it provides the highest earnings yield. But intelligent investors ask why the market is ascribing a 25% premium to company B’s value and dig deeper.

Does this help? [Relabeled table referring to the case study above]

Buffett chose Company B (See’s Candy) in 1972, and it was the correct decision because it was an asset-light company with abundant economic goodwill.

There’s a valuable lesson here for all of us. In relation to programmatic acquirers, they do trade at elevated valuation multiples, but usually for good reason. Don’t allow this superficial means of screening companies to lead you into the wrong investments.

Asset-Light Advantage in Times of Inflation

Let’s now turn our attention to the advantages of being asset-light in an inflationary environment.

Traditional wisdom, which as Charlie Munger would say is ‘long on tradition, short on wisdom’, holds that inflation protection is best provided by businesses laden with natural resources, plants, machinery or other tangible assets (”In Goods We Trust”).

Yet it doesn’t work that way in practice.

Asset-heavy businesses generally earn low rates of return; rates that often barely provide enough to fund the inflationary maintenance capex needs of existing operations, with little or nothing remaining to invest in growth or distribute to owners.

Also, the effective tax rate on cash flow is higher for asset-heavy firms. The balance sheet cost of maintaining tangible assets increases due to inflation but isn’t immediately tax-deductible. To make matters worse, by the time it’s depreciated, the real replacement cost (maintenance capex) is significantly higher than the item labeled depreciation.

Similarly, since inventory and receivables are correctly included in tangible assets, firms investing in working capital get no break from the taxman on their opportunity cost.

Meanwhile, asset-light firms enjoy lower tangible capex needs and can sometimes benefit from free working capital funding.

Which would you prefer?

Working Capital Dynamics

A company’s working capital characteristics significantly affect its ability to grow profitably and navigate business cycles. Nearly all firms operate with positive working capital, they receive cash some time after recording revenue. A positive working capital balance represents invested capital that must be funded with debt or equity. As revenue grows, so do working capital requirements and the capital needed to fuel operations. Working capital needs drag on returns on capital and the firm’s ability to produce profitable growth.

Some programmatic acquirers that buy product companies rely on their reputation as a dependable supplier for its customers. To achieve this they operate an “always in stock” model, which means that a large amount of working capital is tied up in inventory. This acts as a drag on performance.

However, some programmatic acquirers are lucky enough to reverse this situation. They collect revenue upfront - maybe they receive payment on the sale of goods before having to pay their suppliers, or perhaps they charge a subscription fee upfront before supplying the service. Tax accrues on earnings recognition not cash collection, so while most companies finance tax liabilities before receiving cash, those with negative working capital benefit from flipping the script. All of this is tantamount to receiving free financing, which fuels growth.

For a firm operating with negative working capital, growth actually provides more capital for management allocation. Instead of requiring incremental capital to support growth, the firm finds itself with excess cash to invest in organic growth or acquisitions.

Imagine running a business where the more you grow, the more free cash you have. Supermarkets are perfect examples. They receive cash today for goods sold in store when they’re not required to pay suppliers for perhaps 90 days. That’s a rolling 90-day free credit facility. The bigger the business becomes, the more free cash it has.

This parallels the float Buffett generates on insurance operations and uses to grow Berkshire Hathaway.

Last, but by no means least, asset-light firms often can tax-deduct intangible investments by expensing them upfront on the income statement (software businesses are perfect examples). The full tax benefit is received on an asset requiring little or no maintenance that becomes a recurring revenue stream.

The moral: while all businesses are hurt by inflation, those needing little in tangible assets are hurt least.

Final Thoughts

The disconnect between accounting goodwill and economic goodwill isn’t merely an academic curiosity, it’s the difference between mediocre returns and compounding wealth over decades.

While accountants debate amortization schedules and impairment tests, the real story plays out in the factors that never make it onto a balance sheet. The companies that turn small investments into fortunes are those where economic goodwill strengthens with time, not fades.

Take Constellation Software as an example. If you had invested $2.5 million at its 2006 IPO, that stake would be worth about $1 billion today, without you lifting a finger. The key wasn’t luck; it was placing your capital in the hands of a founder who deeply understood the principles we’ve discussed.

Constellation’s success isn’t mysterious. It’s an asset-light, capital-efficient compounder that converts growth into free cash flow.

In inflationary times especially, these businesses don’t just survive, they thrive. Subscription revenues rise with inflation, yet the underlying investment was made with dollars that are now worth less. With minimal maintenance spending, R&D outlays, or capital expenditures, their return on invested capital naturally expands over time.

Your edge as an investor lies in seeing what accountants overlook. When you come across a disciplined acquirer trading at what seems like a high multiple, resist the urge to dismiss it. Instead, ask: Is this business quietly accumulating economic goodwill across a portfolio of high-return assets? Does it need much in the way of tangible assets to grow? Can it reinvest at strong rates without constant dilution or leverage?

These questions matter infinitely more than whether the P/E ratio looks comfortable by traditional standards. The companies that seem expensive today may well prove to be tomorrow’s bargains if they’re compounding invisible value that eventually becomes impossible to ignore.

Master this distinction, and you’ll stop being misled by conventional metrics.

Focus on economic reality rather than accounting fiction.

This is now the sixth post in the Acquisiiton-as-a-Business (AaaB) series. If you missed the others, here are the links:

Relais Group investment analysis

Fairfax India (podcast/video presentation)

Haunted by Valuing Programmatic Acquirers? (this post)

Thank you James!! I was reading Buffett's Annual Letters and couldn't understand the part where $1 of additional capital contributed in See's created more than $3 of nominal value. Your writing is easy to understand. The connection(latticework) made with negative working capital, and software companies's expensing R&D cost and resultant increase in invested capital is admirable.

Awesome post, and enjoyed the accounting comparison to Lifco