I am about to explain to you why dividend policy is so important to your investment returns, but not in the manner that you expect. After reading this you will have an entirely different perspective.

This story begins in 1973 when legendary CEO John Malone began his reign at TCI (Tele-Communications Inc)

Malone, a doctor of mathematics, understood that maximising earnings per share (EPS) on the income statement, as all companies did back then (and many still do today), was entirely the wrong approach. Malone knew that higher earnings numbers meant higher taxes.

He realised that the best strategy for his company was to use all available tools to minimise reported earnings thereby mitigating tax liabilities which would enable him to fund internal growth and acquisitions with pre-tax cash flow.

For example, Malone was not afraid to utilise relatively large amounts of debt to grow the business. He knew that interest payments are a tax deductible and that mitigating tax liabilities by increasing debt meant that he could apply more of the cash generated by his business in a manner that would compound for the benefit of shareholders rather than simply handing it over to the tax man. Said differently, he believed financial leverage had two important attributes: it magnified financial returns and it helped shelter pre-tax cash flows from the tax man.

Malone also managed the depreciation and amortisation of capital assets in a manner that optimized tax efficiency, something that will be of relevance later in this story.

It is difficult to overstate how unconventional Malone’s approach was back in the 1970s. While all other companies sought to maximise reported EPS in order to attract investors, he did everything in his power to minimise EPS. This approach mortified the analysts on Wall Street because for them EPS numbers and the Price-to-Earnings ratio as a measure of value had always been the holy grail.

Many other great CEOs have since followed suit, including Jeff Bezos at Amazon, but Malone was the first to move away from the Wall Street play book.

“When forced to choose between optimizing the appearance of our GAAP accounting and maximizing the present value of future cash flows, we’ll take the cash flows”

Jeff Bezos

You will appreciate that using EPS to evaluate TCI would have led an analyst to reach entirely the wrong conclusion about the company. Its EPS was low and its PE ratio unattractively high. A conventional analyst would have run for the hills rather than investing in this company because conventional valuation metrics were useless.

You may be surprised to learn that during Malone’s term as CEO from 1973 to 1998 he generated a compound annual return for his shareholders of 30.3%. In other words, each dollar invested in TCI over that 25 year period would have grown to $900, yet it would have only been worth $22 if invested in the S&P500 for the same period!

In lieu of EPS, Malone emphasized cash flow to lenders and to his investors. He explained that the important metric was how much cash the business was capable of generating. He tried to educate Wall Street analysts that they shouldn’t focus on the bottom line. He told them to look at Earnings Before Interest, Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation (which provides the acronym EBITDA). The funding costs and D&A that I mentioned earlier were used as tools to mitigate corporate taxes and so the all important number was the earnings before interest, tax and D&A are applied. This is the true earnings power of the business. So this is how the ubiquitous term EBITDA was first introduced into the business lexicon by John Malone in the 1970s.

‘So how is this relevant to dividend payments?’ I hear you ask.

Allow me to explain. Dividends are paid out of taxed corporate earnings. They are then subject to income tax when received by the shareholder, so they are subject to a double-jeopardy in terms of taxation. Let us assume that corporation tax is 25% and income tax 40%: every $1 of pre-tax profit generated by the business will become 45 cents in the pocket of the shareholder if paid as a dividend. But the story doesn’t end there. The poor investor has the frictional cost of reinvesting that capital, crossing the bid/ask spread and paying transaction fees, so the amount reinvested may be closer to 43 cents.

How many years of compounded growth do you think it will take for that 43 cents to return to its original $1 value?

Why would any right minded investor opt for this when instead the business could have reduced its bottom line by reinvesting that full $1 in the business on a tax deductible basis at an attractive rate of return? If the company is generating a ROA of 10% then in place of a 43 cent net dividend the investor will, after a year, have an additional $1.10 of equity in the business.

It isn’t rocket science, just elementary mathematics. But so few investors, or indeed CEOs, appreciate this.

The best investors and CEOs understand this perfectly. Warren Buffett has, on numerous occasions, advocated the benefits of compounding pre-tax growth.

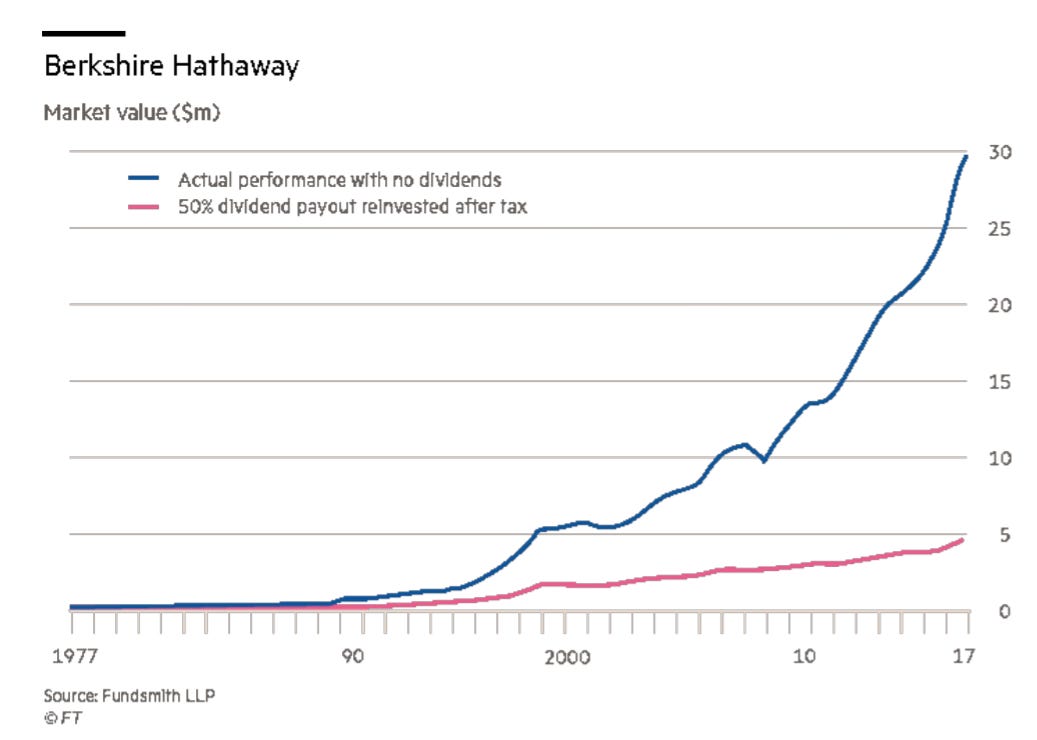

Many very good companies including Berkshire Hathaway and Amazon do not pay dividends but have provided their investors with phenomenal investment returns.

Many CEOs will tell you that they must pay dividends in order to attract institutional investors. I say nonsense. Berkshire Hathaway, Google and Amazon have never struggled to attract institutional investors.

It is true that the shareholder base may shift from income investors to growth investors if dividends cease to be paid. Does that matter? Should the company sacrifice growth opportunities simply to appease one group of investors? The answer to both questions is ‘no’. The company must be run in a manner that generates optimal returns because the management are, de-facto, trustees of shareholder capital.

Wall Street encourages CEOs to pay dividends because cash paid out to investors needs to be reinvested somewhere and who do you think benefits from all of that activity? Wall street generates billions of Dollars every year from investment activity and all of that gain for them is frictional cost to investors. In other words, what helps Wall Street hurts the investor.

Additionally, having paid out corporate capital as dividends, there is nothing that the CEO would like more than for the recipients of those dividends to reinvest that money back in the business, but there is no guarantee that they will do so. There is an investment universe out there and the money is likely to find its way into an alternative opportunity instead.

These problems are easily solved for the mutual benefit of both the investor and for the company by simply not paying a dividends.

The fact of the matter is that dividends are such a poor way of returning capital to shareholders. They should only be used as a last resort. Reinvestment should always be a first priority for capital allocation if returns above the cost of capital can be achieved. Paying down excessive levels of debt is another sensible use of capital. If the shares are selling at a discount to intrinsic value, then buy-backs are very accretive to shareholder returns (click here to learn more about stock buy-backs). Dividends are bottom of the list if no other capital allocation options exist.

If you are invested in a growth company or a business that is trading at a discount to intrinsic value and that business is paying dividends then make your voice heard. You may also like to point out that the CEO spends a great deal of time selling the virtues of the company to investors in order to attract new investment capital (corporate reports, investor presentations, etc.) Is it not contradictory to be selling the business as a sound investment prospect when the company is giving away capital rather than investing in itself?

If you are an investor that relies on investment income then, in lieu of dividends, sell a small percentage of your holding and allow the remainder to compound. This way you decide how much you need and when to create an income tax liability that suits your circumstances. You don’t need dividends. Period. Dividends only benefit the tax man and what benefits him hurts you.

In the event that your remain unconvinced, allow me to furnish you with a final example.

Back in 1972, there existed a group of 50 top-performing stocks in the US collectively known as the “Nifty Fifty.” It included iconic companies such as McDonald's, Coca Cola, Walt Disney, American Express, Gillette, and General Electric. Fast forward half a century to the end of 2022, and many of these companies remain top performers. If an investor had evenly distributed their investment across all 50 companies and held onto them until the end of 2022, they would have enjoyed a compounded annualized return of 10.08%. To put it in tangible terms, a $100 investment in each of these companies (totaling $5,000) would have grown to an impressive $609,020. This is particularly relevant because these companies not only paid regular dividends but also experienced capital bleed due to taxes, limiting available capital for reinvestment in growth.

Alternatively, investors could have chosen to invest the entire $5,000 sum in a single business, Berkshire Hathaway. This is a company which ironically was not considered worthy of the Nifty Fifty back in 1972. As explained earlier in the chapter, Buffett does not pay dividends and strategically avoids capital bleed, resulting in more aggressive compounding of growth. Over the same half-century period, Berkshire Hathaway compounded at an impressive annualized 18.9%, meaning that the investor would have ended 2022 with a staggering $28.7 million, highlighting the extraordinary power of compounding retained earnings.

As a side note, Berkshire Hathaway paid a singular dividend on 3rd January 1967, amounting to ten cents per share, translating to a meager 0.54% yield based on the stock's value of $17.87 at the time. Warren Buffett openly acknowledges this dividend as a mistake, emphasizing this perspective as recently as the 2023 Annual Meeting. Interestingly, on that particular date, the company distributed a total of $101,755 in dividends. It may surprise you to discover that had it instead chosen not to pay that dividend and instead retained those earnings, they would have grown to over $3.1 billion by 2023.

The following chart plots the growth in the Berkshire Hathaway market capitalization for the 40 years from 1977 until 2017. One line shows the actual performance, while the other demonstrates the growth trajectory had it paid out 50% of earnings to shareholders and only retained the other 50%.

Do you still want dividends? I hope not. If you do, then perhaps investing isn’t the game for you.