LVMH, Kering or Hermès - What? Why?

Difficult Questions: What's Behind Successful Luxury Brands - Is It Just An Illusion?

DISCLAIMER & DISCLOSURE: The author holds no positions in any company mentioned at the date of publication but that may change. The views expressed are those of the author and may change without notice. The author has no duty or obligation to update this information. Some content is sourced from third parties believed to be reliable, but accuracy is not guaranteed. Forward-looking statements involve assumptions, risks, and uncertainties, meaning actual outcomes may differ from those envisaged in this analysis. Past performance is not indicative of future results. All investments carry risk, including financial loss. This analysis is for educational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or recommendations of any kind. Conduct your own research and seek professional advice before investing.

This isn’t equity analysis in the traditional sense. You won’t find charts of revenue growth, margin breakdowns, or endless talk of valuations here. Instead, it’s a deeper dive into the soul of the luxury and fashion world - an exploration of the big, qualitative themes that shape these brands from the inside out. It’s about understanding the different mindsets behind several well known companies, the philosophies that drive them, and ultimately, asking the more interesting question: which of these approaches truly serves the long-term investor best?

Why Should I Care About Luxury Goods and Fashion?

The luxury goods industry stands as one of the most dynamic and resilient sectors globally, characterized by its ability to consistently outperform broader markets. Luxury companies operate in a high-margin environment, driven by exclusivity, exceptional craftsmanship, and heritage-rich branding.

Do you invest in businesses that own diverse portfolios of luxury and premium labels?

If so, this post matters to you because it uncovers a truth about an industry focused on crafting external appearances that often mask the realities within.

Here are some examples of groups that collect luxury brands:

LVMH (Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy) (Paris: MC): Owns iconic fashion brands like Louis Vuitton, Christian Dior, Fendi, and Celine.

Kering (Paris: KER): Portfolio includes Gucci, Saint Laurent, Bottega Veneta, and Balenciaga.

Tapestry (NYSE: TPR): Owns Coach, Kate Spade, and Stuart Weitzman, and is acquiring Capri Holdings, adding Versace, Michael Kors, and Jimmy Choo.

PVH Corp (NYSE: PVH): Manages global brands such as Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger.

V.F. Corporation (NYSE: VFC): Owns premium labels like Supreme, Timberland, and The North Face (excluding Japan and Korea, where The North Face is independently owned by Goldwin Co. Ltd.).

Estée Lauder (NYSE: EL): Primarily known for beauty products but also owns fashion-related brands like Tom Ford.

Now let’s ask some really difficult questions which are worthy of consideration for any investor. Perhaps this will change the way you think about these companies in future.

The Ethical Dilemma

Imagine picking up a new book because it has Charles Dickens stamped on the cover. His name instantly lends credibility and guarantees the quality of the book’s content. But as you turn the pages, it becomes clear: he didn’t write a word of it. Someone else did - poorly - and they're just using his name to sell more copies. You’d feel cheated, right?

Yet this very practice is widespread in the fashion industry. Christian Dior died in 1957, so what does it mean to buy Christian Dior today? Are Gucci or Balenciaga the same brands they were 60 years ago? They are certainly in different ownership.

Fashion is more than fabric and logos. It's a form of art - deeply personal, built on a designer’s unique vision, philosophy, and creativity. When you slap a legendary name on something entirely new and unrelated to the original creator, it raises a serious question: Is that honest? Is it ethical?

Some argue this is no different from what carmakers do. Ferrari still carries its founders' names decades after his death. But here's the catch - cars are engineered by teams and built through innovation that evolves over time. People aren’t paying for the creativity of an individual and, in any event, the name “Ferrari” is a family name that was used for a company run by generations of the same family with that name. So it isn’t the same thing.

Similarly with Hermès? The brand stands for the highest quality and exclusivity - that’s what consumers are buying, not the unique design of an individual. The company compromises on nothing and people pay for that - not because it was created by Thierry Hermès, the company’s long dead founder.

Fashion, on the other hand, trades heavily on the individual genius of one person - something that can’t be handed down.

And let’s be honest - if a modern day fashion designer truly believes in their talent, why not build a brand under their own name? Why lean on the legacy of someone long gone?

What we often see instead is a smoke-and-mirrors game: luxury brands leveraging legendary names to create an illusion of exclusivity and timeless quality. But behind the curtain, the magic is gone. What's left is marketing - profitable, yes - but arguably dishonest.

In any other industry, knowingly misleading customers like this could be considered fraud. In fashion? It's just business as usual.

Borrowing brilliance from the dead might make money - but that doesn’t make it right.

This exposé digs deeper on this theme, uncovers where this deceitful practice began and asks what it means for companies that collect brands, such as Kering and LVMH.

The narrative spotlights three iconic figures - Coco Chanel, Christian Dior, and Cristóbal Balenciaga - whose contributions have shaped a story that remains largely untold - and brings us through to the modern day conglomerates mentioned earlier.

What may surprise you most is that Coco Chanel was the one who planted the seeds for this troubling transformation in the fashion world, while Christian Dior took it to unprecedented heights. These two visionaries, while brilliant, are arguably responsible for the industry’s current state. In contrast, Cristóbal Balenciaga was a man of noble character and unwavering integrity. Yet, ironically, his name now sits at the center of this scandal.

Let’s dive in to the story…

Coco Chanel

Born in the Loire Valley region of France on 19 August 1883, Chanel’s parents were an unmarried drunk peddler and a poor woman from a workhouse. She and her four siblings were abandoned to an orphanage and this is where she learned to sew.

Subsequently, on reaching adulthood, she found herself out in the big wide world with absolutely no money or material possessions to her name. She had to hustle to survive and this meant taking on a variety of jobs.

Although her birth name was Gabrielle, she adopted "Coco" as her stage name during a brief singing career in cabaret bars. The name stuck and followed her through life.

Coco Chanel came across some cheap material that was traditionally use for men’s underwear and made herself a warm dress to shield her from the cold. Other women asked if she could make something similar for them, and so by chance she found herself in the dress making business.

As an unloved orphan, she was about as far removed from high society and the establishment as one could be. This imbued her with a rebellious streak and she loved to challenge societal norms and the fashion conventions of the day.

Chanel rejected the restrictive, hyper-feminine styles of the time, favouring simplicity, comfort, and practicality. This lead to the creation of casual yet elegant designs that liberated women from corsets.

She often wore her lovers’ clothing and, inspired by menswear, she incorporated androgynous elements into her designs for women. Her bold choices, such as popularizing trousers for women and the "Little Black Dress," empowered women to embrace freedom in fashion.

Coincidentally, this was a period of significant social change in which women were embracing independence and seeking to break free from traditional patriarchal norms. Women’s suffrage was gaining momentum, with organizations like the French Union for Women’s Suffrage (UFSF) advocating for the right to vote and other feminist causes.

The feminist movement influenced demand among Parisian high society and served as a driving force for Chanel and other designers to innovate and explore the boundaries of their craft.

This fostered a concentration of talent and served as a fertile ground for designers. The synergy of skill and knowledge within this Parisian milieu resulted in the city becoming a hotbed for many renowned fashion houses.

Had Chanel found herself anywhere else but Paris, at any time other than the early 20th century, she would almost certainly never have succeeded in the world of avant-garde fashion. As such, she was incredibly fortunate to find herself in the right place at the right time.

By 1921, at 38-years old, Coco Chanel, was beginning to build quite a reputation for herself in Paris.

In line with these changing times, Chanel envisioned a fragrance for the liberated woman - something bold and modern that resonated with the independent spirit of the era. So she asked French-Russian chemist and perfumer, Ernest Beaux, to create a unique fragrance for her to sell alongside her clothing.

At the time, women’s perfumes fell into two distinct categories: respectable women wore the essence of a single garden flower, while women deemed unrespectable, such as courtesans and prostitutes, favored musky, sexually provocative scents. Both of these defined women with reference to their place in a patriarchal society, so Chanel wanted a scent that would allow them to break free.

Ernest Beaux presented Chanel with several scents in small glass vials, each marked with a number. She chose the fifth vial, and the number became its name, thus Chanel No. 5 was born. Rather ironically, Chanel herself neither formulated the perfume nor devoted any effort to naming it, yet this seemingly unassuming liquid became the cornerstone of Chanel’s immense success, cementing her legacy.

Even the perfume’s bottle reflected Chanel’s lack of involvement. Despite her reputation as a creative designer, Chanel paid little attention to its presentation. In an era defined by the elaborate artistry of art nouveau, where master glassmakers like Lalique and Baccarat crafted ornate fragrance bottles, Chanel opted for a simple, square, transparent glass bottle - so plain it was almost invisible.

This minimalism suggests Chanel regarded the perfume as a side project, unworthy of her full attention. Moreover, Chanel lacked both the resources and expertise to operate a perfume business on her own. Recognizing this, Théophile Bader, founder of the Paris department store Galeries Lafayette, introduced her to Pierre Wertheimer at the Longchamps horse races in 1922.

This meeting led to a partnership with Pierre and his brother Paul Wertheimer, directors of the perfume house Bourgeois. Together, they established a new corporate entity, Parfums Chanel. The Wertheimers funded the business, managing its production, marketing, and distribution, while Bader also invested. The arrangement gave the Wertheimers a 70% stake in the company, Bader 20%, and Chanel herself 10%, based on her contribution of the commissioned scent and the licensing of the Chanel name. This partnership laid the groundwork for Chanel No. 5's global success, turning a modest endeavor into a cultural phenomenon.

It would be easy to criticize Coco Chanel for relinquishing so much equity in her perfume business, but in reality, it was Chanel No. 5 that secured her legacy.

The perfume provided stable cash flows that financed Chanel’s fashion ventures and ensured her brand's survival. Without the Wertheimer brothers, Chanel may have faded into obscurity, her name never becoming synonymous with haute couture.

In the event, the Wertheimer brothers were instrumental in Chanel’s success, helping her rise to become one of the wealthiest women in the world while pursuing her passion for fashion.

Throughout her life, Chanel would do anything to further her own cause. For instance, during World War II, when the Germans occupied France, she became romantically involved with a high ranking Nazi officer. Whether she sympathized with Nazi ideology is unclear, but she was, by all accounts, ethically bankrupt and morally void.

Her smile was a mask, carefully tailored to win trust, yet beneath it was a ruthless hunger that saw others not as companions, but as stepping stones to be used and discarded. She walked through life with a single-minded focus, her path littered with the shattered remains of friendships and broken promises - each sacrifice a price she was more than willing to pay. Empathy was a language she never learned, and loyalty, to her was a tool of convenience rather than a bond of truth. In her world, the ends always justify the means, no matter how much collateral damage it caused.

Rather than being thankful for all the Wertheimer brothers had done for her, Chanel proved to be duplicitous. When the Nazi regime began seizing Jewish-owned businesses, Chanel, aware that the Wertheimers were Jewish, sought to use the situation to her advantage and attempted to claim sole ownership of Parfums Chanel.

The brothers had fled Europe and sought refuge from Nazi persecution in the U.S.

On May 5, 1941, Coco Chanel surreptitiously petitioned the German authorities, arguing, “I have an indisputable right of priority… the profits I have received from my creations… are disproportionate.” She described Parfums Chanel as “legally abandoned” by its Jewish owners and sought to take control.

Unbeknownst to Chanel, the Wertheimers had anticipated such confiscations and, in May 1940, legally transferred control of Parfums Chanel to a friend, a non-Jewish French industrialist, named Félix Amiot. After the war, Amiot returned the business to his friends, the Wertheimers.

By the mid-1940s, Chanel No. 5 was generating $9 million in annual global sales and, once again, rather than being thankful to the Wertheimers for making it a success, Chanel remained determined to regain control of the company.

This time she began publicly discrediting the perfume, claiming it was no longer the original fragrance she had commissioned and refusing to endorse what she called an inferior product. The Wertheimers countered by hiring Gregory Thomas, who implemented strict quality control measures - he later served as president of Chanel U.S. for 32 years.

Undeterred, Chanel subsequently filed a lawsuit, seeking an injunction to stop the manufacturing and sale of Chanel No. 5, demanding the restoration of her sole rights to the formula and production.

Although the Wertheimers had a strong legal case, they understood the risks of exposing Chanel’s collaboration with the Nazis during World War II. Such a revelation could irreparably harm her reputation and the brand’s image, jeopardizing their shared interests.

Rather than engage in a damaging legal battle, the Wertheimers negotiated a settlement. In 1947, Coco Chanel received $400,000 in cash, representing wartime profits from the sales of Chanel No. 5 perfume, she was granted 2% of all worldwide sales of the perfume, she received a perpetual monthly stipend that covered all of her expenses and in return she relinquished all rights to the name ‘Coco Chanel’. Following the acquisition of the ‟haute couture” business by ‟Parfums Chanel”, the company took the new name ‟Chanel SA” (‟Chanel Société Anonyme”).

By this time Chanel was in her mid-60s and so this was effectively her retirement ticket. The deal earned her approximately $25 million annually, making her one of the richest women in the world at the time.

Today, the Wertheimer family continues to privately own the entire Chanel empire, with Alain and Gérard Wertheimer, the great-grandsons of Pierre Wertheimer, listed among the Forbes 400 billionaires. The enduring success of Chanel No. 5 has been a cornerstone of the company’s financial stability and growth, sustaining the brand’s prominence over decades.

In stark contrast, Chanel had a wretched childhood in an orphanage run by nuns, without receiving any love. This shaped the person that she became. She was known for being demanding and sometimes difficult, living life on her own terms. Her life was marked by complicated relationships and she was known to associate with artists and intellectuals like Salvador Dali, Winston Churchill, and Jean Cocteau. She never married and was known for her affairs with wealthy and influential men who often supported her business and social ambitions. Despite the money she had, hers is not a life that should be coveted.

Coco Chanel passed away in 1971 in her apartment at The Ritz hotel, very much unloved and spiritually alone. Her final words were, ‘May my legend prosper and thrive. I wish it a long and happy life.’

While Chanel has been celebrated in literature as a commercial genius, her success was more the result of simplicity and serendipity than any exceptional talent or virtue on her part. In truth, her achievements often came in spite of her many character flaws rather than because of qualities that merit great acclaim.

Christian Dior

The really interesting part of the story is that despite being regarded as an haute couturier, she owes her immense success to a perfume that she didn’t create and which simply bore her name. Interestingly, Christian Dior followed a similar playbook.

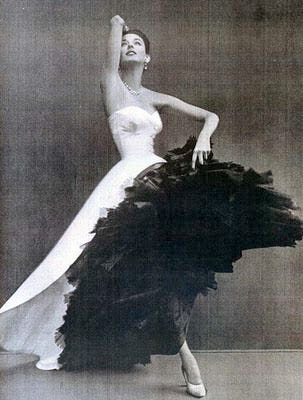

He launched his career after World War II by introducing the groundbreaking "New Look" in 1947 - the same year Chanel sold out to the Wertheimer brothers. This collection of dresses marked a dramatic departure from wartime austerity. Featuring cinched waists, full skirts, and luxurious fabrics, his designs celebrated femininity and opulence, contrasting the utilitarian styles of the war years.

This aesthetic resonated with a society eager for beauty and extravagance after years of rationing and restrictions. Backed by textile magnate Marcel Boussac, Dior's creations revitalized Paris as a fashion capital and became globally iconic, appealing to women seeking glamour and a return to pre-war elegance.

The really interesting part of the story is that Christian Dior revolutionized the fashion industry by pioneering the concept of luxury brand licensing. This innovative strategy enabled the rapid and profitable expansion of the Dior name. By leasing his trademark and brand identity to other companies, Dior allowed licensees to produce and sell products such as hats, gloves, shoes, eyewear, perfumes, stockings, and furs under the Dior label. In return, he earned substantial royalties from their efforts, creating what was essentially a 100% gross margin business. This approach mirrors what Chanel, perhaps unintentionally, achieved with her perfume line.

Initially, the French Chamber of Couture criticized Dior’s strategy, claiming it cheapened the industry. However, its profitability was undeniable. Dior's licensing model became so successful that nearly every major fashion house adopted it, reshaping the luxury fashion industry's business model.

The next time you come across a premium-priced Gucci watch, a Calvin Klein perfume, or Prada sunglasses, take a moment to reflect on their true origin. The high price of these items often stems not from their inherent quality but from the power of the brand name they bear - and its the name of a company that invariably had no part in the manufacture of the item! In a materialistic world where consumers are fixated on displaying status, a simple logo can transform an ordinary product into a perceived symbol of luxury. As long as people willingly embrace this exploitation, it's hard to fault those profiting from it. Even sports stars and musicians have their own premium priced perfume and clothing ranges these days - where does it end?

Cristóbal Balenciaga

This brings us to the chapter of the story that I lament, because it is so terribly sad.

Cristóbal Balenciaga was regarded as the pinnacle of haute couture by his contemporaries, including Coco Chanel and Christian Dior. Chanel described him as "the only authentic couturier" capable of designing, cutting, assembling, and sewing a dress entirely by himself. Dior, despite being a fierce competitor, hailed Balenciaga as "the master of us all," likening haute couture to an orchestra with Balenciaga as the sole conductor.

Balenciaga's perfectionism was the stuff of legend. Known for his exacting standards and meticulous attention to detail, his designs were distinguished by their flawless tailoring and construction. Many of his creations were so exquisitely crafted that they have been passed down through generations, worn by the daughters and granddaughters of their original high-society owners. For these affluent families, recycling clothing isn't a necessity - instead an original Balenciaga dress is valued as an heirloom, just like a piece of fine jewelry. They are coveted by fashion collectors and museums, achieving eye-watering valuations at auction.

By 1968, as his career drew to a close, Balenciaga made the bold decision to shutter his fashion house rather than compromise the integrity of his name. Believing no other haute couturier could uphold his impossibly high standards, he refused to pass the business to anyone else. His career was driven by an unwavering pursuit of perfection, not the pursuit of wealth.

Rather than risk tarnishing the legacy that he had painstakingly built over his lifetime, Balenciaga refused to sell his very valuable business and instead took the bold decision to cease operations entirely. In 1967, at the age of 72, he shuttered his business, and shortly thereafter, he passed away. For him it was never about the money.

However, his story didn’t end there. Very much against his wishes, the brand was subsequently resurrected as other sought to cash in on Balenciaga’s success.

In 2001, it was acquired by Kering, a French multinational luxury goods conglomerate (formerly Pinault S.A.), which also owns brands like Gucci and Yves Saint Laurent.

Today, under Kering’s ownership, the Balenciaga name has been applied to a wide array of low-quality, seemingly mass-produced merchandise. One can only imagine Cristóbal Balenciaga turning in his grave at what his once-pristine brand has now become!

Kering & LVMH

Critics have expressed concerns about Kering's management of its luxury brand portfolio, particularly Gucci and Balenciaga. They argue that the company has become overly reliant on fashion-driven products, straying from the timeless luxury that originally defined these brands.

Kering's flagship brand, Gucci, has faced significant challenges in recent times. In the first quarter of 2024, Gucci reported an 18% decline in organic revenues, prompting a profit warning for Kering. Critics point to the brand’s heavy focus on fleeting fashion trends rather than enduring luxury as a key factor in its struggles.

"When you're exposed to fashion, it's intrinsically more volatile because fashion waves come and go."

Mario Ortelli

Additionally, Kering’s strategy of offering discounts at Gucci outlets has drawn scrutiny for potentially undermining the brand’s luxury image. This practice is considered unthinkable for luxury brands such as Rolex and Hermès.

LVMH’s stock is now down approximately 45% on where it traded just two years ago. What happened?

In the words of Coco Chanel, “Fashion changes, but style endures.” But what happens when labels stop offering style and quality, opting to sells ordinary production line goods (probably made in China), for a premium price simply because they have a brand label on them?

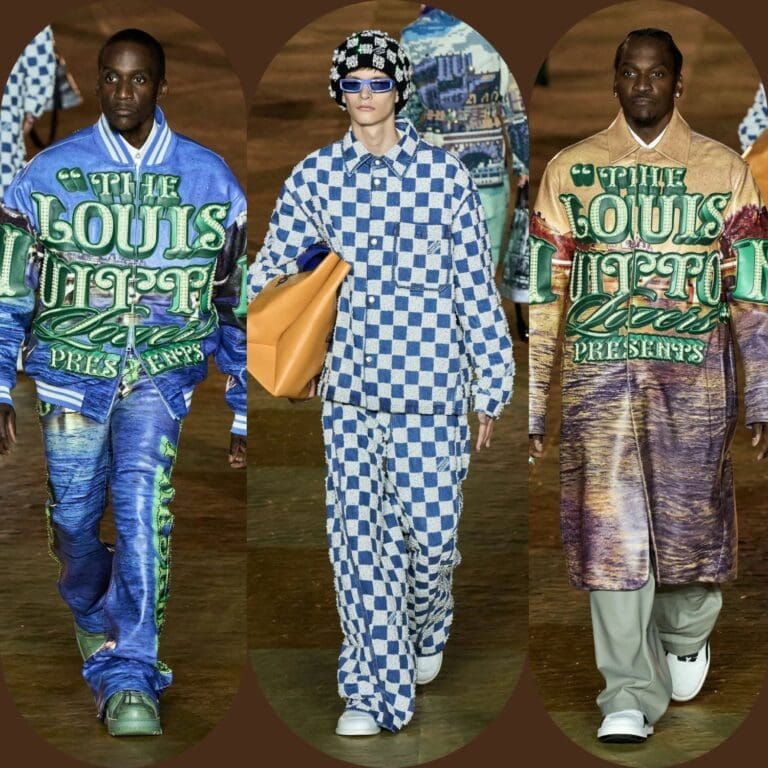

Would you pay $6,050 for these plastic Louis Vuitton sneakers? Or would you rather sneakers made by experts in the field, such as Adidas or Nike, who invest in R&D to optimize the performance of the shoe and which are available at a fraction of the price? These yellow sneakers are probably worth no more than $50, so the other $6,000 on the price tag is simply for the name!

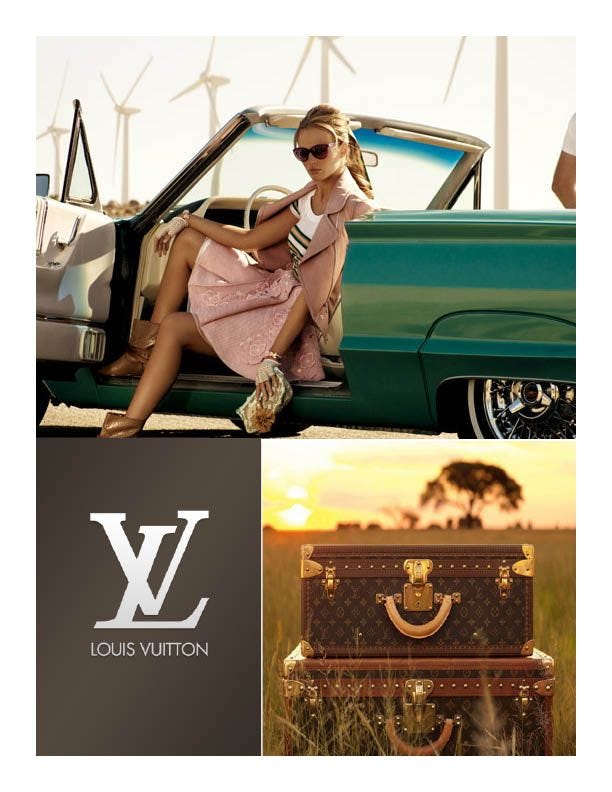

Compare the images below which demonstrate what the Louis Vuitton brand used to represent (style and sophistication), versus what it represents today (I have no words).

STYLE AND SOPHISTICATION - LEGACY LOUIS VUITTON:

compared to:

A FANCY DRESS COSTUME PARTY - LOUIS VUITTON TODAY:

LVMH has certainly had a strong run, comfortably outperforming the broader French market, but lately, it feels like the magic is fading. The stock has stalled, even starting to surrender some of those hard-won gains (see yellow line on the chart below).

As LVMH loses its shine, Hermès has quietly slipped past it to become the world’s largest luxury company.

What’s striking about Hermès is how unwavering it has been. While giants like LVMH and Kering have expanded through a flurry of luxury brand acquisitions - milking them to extremes simply to juice profits - Hermès has taken a different path. It hasn’t played the empire-building game. Instead, it’s stayed close to its roots, protecting the purity of its brand, and that discipline is paying off.

Becoming an Hermès artisan is like joining a secret guild of master craftspeople. It requires at least 18 months of learning at École Hermès des savoir-faire, the company’s dedicated leatherworking school, where they are trained in age-old techniques like the legendary saddle stitch. Every Hermès creation is a true work of art crafted by hands that have inherited nearly two centuries of savoir-faire.

Imagine a linear spectrum. Up high on the far left, you have Hermes, representing an unconditional commitment to the integrity of its brand. At the bottom, on the far right is Kering, where the integrity of the brand is secondary to short-term profitability. LVMH, in my humble opinion, has historically leaned towards the left but appears to be rapidly sliding to the right.

Said differently, while the folk at Hermès are on a mission to produce a level of perfection that others are simply unable to meet. those at LVMH and Kering seem to be adopting a more mercenary type of approach. Slapping a prestigious label on products that lack both style and quality may boost short-term profits, but at what cost? Over time, a brand’s reputation for excellence will surely erode if they continue down this path.

Between the three, it’s Hermès that stands out. I just don’t feel at ease with the direction of travel for LVMH and Kering. There's a sense that their strategy is starting to feel a bit tired, a bit too calculated. But Hermès? That’s a business I’d invest in with confidence.

This situation raises important questions:

Is consumerism eroding the foundations of parts of the luxury industry?

Have the companies that tried to exploit once-glorious brands to charge unjustifiably high prices for inferior products finally faced the justice they deserve?

What do you think? Do you agree?

This is an excellent article and analysis. I recently wrote about the same topic, check it out! https://marcinparis.substack.com/p/when-the-discreet-overtakes-the-grand-4f9?r=5ib925

Excellent writeup