Warren Buffett’s Advice

The Sage of Omaha has always echoed the mantra, "Never Bet Against America," a principle that has served him well throughout his investment career.

However, will this hold true indefinitely? Or was Buffett simply fortunate to be in the right place at the right time?

The decades ahead of us will look very different to those in the rear view mirror.

For the past 50 years, the petrodollar system has been a cornerstone of the U.S. dollar's dominance as the world's primary reserve currency, significantly fueling asset market booms. However, change is occurring and we are witnessing a significant shift in geopolitics and global economics. This change could have several potential consequences, including an impact on the U.S. stock market.

Let’s dive into the details to better understand the situation - stay with me on this because it isn’t as heavy as it looks and your investments may be impacted.

What Are Petrodollars?

The Bretton Woods Agreement established the U.S. dollar as the world's primary reserve currency, initially pegged to gold, facilitating international trade and economic stability post-World War II.

The fundamental flaw in this system, known as the Triffin dilemma, was that the U.S. could not maintain sufficient gold reserves to back the currency needed for both domestic use and growing international needs.

Massive military spending to fund the Vietnam War eventually caused significant fiscal deficits and inflation, undermining confidence in the U.S.'s ability to maintain the dollar's convertibility to gold at $35 per ounce. This culminated in President Richard Nixon ending the dollar's convertibility to gold in 1971, and most other countries followed suit, creating 'fiat' currencies. These currencies were essentially unbacked paper, valued only because governments declared them legal tender. This shift led to floating exchange rates and increased currency volatility.

Then, in 1973, tensions in the Middle East caused oil prices to skyrocket which created shock-waves through the global economy. In response to this oil crisis, in 1974 the U.S. struck a deal with Saudi Arabia in which it was agreed that oil exports would be priced exclusively in U.S. dollars. In return, the U.S. promised to provide military protection and economic support to Saudi Arabia.

Oil-exporting countries were now receiving dollars for their oil. Concurrently, oil-consuming countries needed to maintain dollar reserves to acquire oil, further bolstering the U.S. dollar's status as the world's primary reserve currency, facilitating its widespread use in international trade and investments.

With the dollar no longer pegged to gold, the U.S. could print as much money as needed. America's largest net export became paper dollars with no intrinsic value, requiring persistent trade deficits to ensure sufficient dollars in the international system.

But ask yourself this: why should businesses and governments in other countries accept endlessly printable paper, with no intrinsic value, from a foreign government as payment for valuable goods and services? Without gold backing, what were they worth? Why exchange oil for paper?

Faced with these concerns, the sensible thing to do was to convert that paper into hard assets. All of those dollars were put to work somewhere and they flooded back into America where they were used for trade (buying U.S. made products) or invested (typically in the stock market or Treasury bonds).

Balance of Trade and the Stock Market

Most countries aim to keep their currencies strong enough to afford essential imports but weak enough to keep exports competitive. Trade balances are thus managed through currency cycles. But as masters of the global reserve currency, the U.S. is unable to balance its trade in this way and so runs a persistent trade deficit.

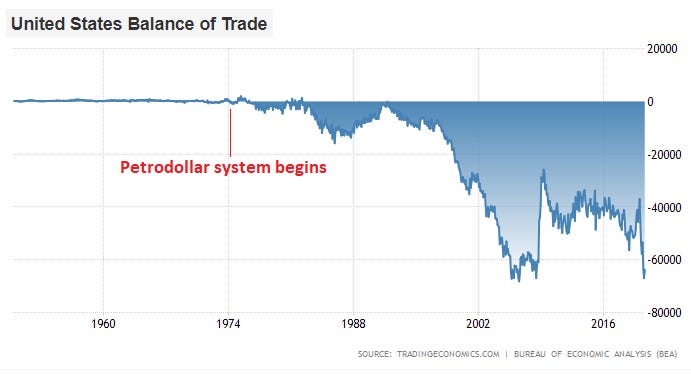

The chart below demonstrates how the U.S. trade deficit has expanded since the beginning of the Petrodollar system.

As demand for the dollar keeps it strong, U.S. exports become relatively more expensive resulting in a draw down on the U.S. manufacturing base which gradually moves overseas to remain competitive.

Accordingly, with less production in the U.S., foreign held dollars are used less to consume U.S. products and more to fund dollar denominated investments instead.

The chart below shows how, over the past 50 years, foreign ownership of U.S. equities has gone from being insignificant prior to the Petrodollar era, to almost 40 percent today. Now you will understand why Buffett’s “never bet against America” held true for the past half a century.

Many oil-exporting nations have established sovereign wealth funds to manage and invest their petrodollar surpluses. These funds have become major investors in U.S. equities, with some holding significant stakes in major U.S. companies. This has increased liquidity and supported higher valuations for U.S. stocks, contributing to the overall growth and performance of the U.S. stock market.

Additionally, the growing U.S. budget deficit needed to be financed, which in turn encouraged the Federal Reserve to keep interest rates low. Thus, the petrodollar system has indirectly made it cheaper for companies to borrow and invest in growth, again supporting higher stock valuations.

Change is Coming

Saudi Arabia's decision to price oil in other currencies aligns with its growing ties to BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), which collectively aim to reduce reliance on the U.S. dollar. This move could lead to a more multipolar world where the influence of Western economies lessens and is balanced by the growing influence of emerging markets.

After World War II, the United States represented over 40% of global GDP. However, this share has since halved in nominal terms and would diminish further if the dollar weakened. Based on purchasing power parity, the U.S. now represents around 15% of global GDP, not bad for a country with only 4 percent of the world’s population, but no longer big enough to sustain the world’s reserve currency.

In fact, globalization has seen the rise of powerful new economies, making international trade too extensive to be priced in the currency of any single country. This shift suggests a move toward a more decentralized global monetary system.

More specifically, the expiration of the petrodollar agreement could spur the formation of new financial blocs. Countries discontent with the dollar's dominance may seek alternative financial systems. This partially explains the rise of cryptocurrencies in recent years.

This weakens the position of the U.S. on the world stage. Previously, controlling the reserve currency allowed the U.S. to impose sanctions on other countries, a formidable power to hold.

Today, sanctioned countries such as Iran and Russia are happy to deal in currencies other than U.S. dollars, while countries such as China and India are happy to oblige. In 2014, Russian exports to India were over 98 percent dollar based, but today Russia is accepting Indian Rupees for its oil - India then benefits from those Rupees being invested back into the Indian economy, rather than dollars being invested in the U.S.

Meanwhile, many countries with large dollar surpluses are no longer content to accumulate U.S. securities. Under its 2013 ‘Belt and Road’ initiative, rather than investing its dollars into the U.S., China began aggressively lending dollar-based loans for infrastructure projects in developing countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Eastern Europe.

The benefits of the Petro-Dollar agreement seem to be tapering off. Demand for dollars is almost certain to decline, and the volume of foreign money being channeled into the U.S. has probably peaked and is likely to diminish in future.

Conclusion

If 40 percent of U.S. equities are owned by foreigners currently holding dollar surpluses, what happens to those positions when dollar surpluses are wound down in favour of other currencies?

If demand for dollars drops, causing the currency to fall into a weakening long term trend, would this accelerate foreign divestment from dollar-based assets?

Never bet against America certainly held true for a long time. But it is unlikely to hold true forever.

The boiler-plate investment firm disclaimer springs to mind: “Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future returns.” This may very well also hold true in the case of U.S. equity markets more generally.

Nice article

Surpluses won't move to other currencies because there are no good investments not denominated in us dollars (such as the us stock market) It's not just the currency, it's the opportunity set. Assets must match liabilities.