Profit: Purpose, or Consequence?

A Case Against Shareholder Primacy and the Rise of the “Statistical Mirage”

At a recent dinner party I was asked what I do for a living. ‘Equity investing,’ I said — perhaps that was a mistake, it sparked a lively debate that went on for quite some time about the purpose of a company.

Is it to generate profits for those that supply it with the capital it needs to operate (its shareholders)? Or is it about something else entirely? That discussion inspired this post.

Nobel Prize-winning American economist Milton Friedman argued that the purpose of a company is to generate returns for shareholders (the Friedman doctrine). In his highly influential 1970 New York Times essay titled “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits,” Friedman argued that a corporate executive is an employee of the business owners (the shareholders) and has a direct responsibility to them.

The doctrine is academically sound, but does it stand up to scrutiny in practice?

For decades, this doctrine of shareholder primacy has served as the North Star for corporate governance, suggesting that if companies focus solely on financial returns, societal benefits will naturally follow.

Yet when we consider it against the long arc of economic development, and especially the shift from a world grounded in production to one dominated by financial abstraction, it becomes clear that Friedman’s view is not only incomplete, it’s a narrow reading of what enterprise has historically been and what it needs to be if progress is to mean anything real.

In his autobiography, ‘My Life and Work’, the entrepreneur Henry Ford took a very different view to that of Friedman. Ford believed that money comes naturally as the result of service. He explained that, “My idea was then, and still is, that if a man did his work well, the price he would get for that work, the profits and all the financial matters, would care for themselves”.

So now we have a contrasting viewpoint. The free market is an “arena of usefulness,” where the financial result, profit, was deeply tethered to the production of real value. In this context, the purpose of a company was production, and profit was the reward for that stewardship.

For most of human history, progress was inseparable from tangible improvement. From the plough to the compass to the printing press, every true advance was something visible, useful and enduring. The steam engine shortened continents; electricity lengthened the day; sanitation and medicine liberated entire populations from the daily threat of disease. These weren’t merely the products of profits; they were civilizational achievements rooted in work, innovation, discipline and a moral order that tied effort to consequence.

The builders of this world were arguably not chasing returns, they were meeting needs, solving problems and turning scarcity into sufficiency through thrift, invention and creativity.

The financial system that enabled the industrial revolution was originally built on the basis that money represented past work. Investment was a partnership between the thrifty savers and the enterprising innovators. In such a world, profit was not a goal in isolation but a signal that one had contributed to benefit society in some way. Enterprise was grounded in the idea that value came from building something that served others.

British entrepreneur Richard Branson captured a similar sentiment when he said, ‘I can honestly say that I have never gone into any business purely to make money. If that is the sole motive, then I believe you’re better off not doing it… Any business that makes somebody else’s life better in some way, will capture value in return... Money is a by-product of success.’

It becomes intriguing how academic theorists can differ in opinion so starkly from business practitioners. The essence of the argument can be distilled into a simple question: “Is money the cause or the effect of a successful business?”

By the late twentieth century, Friedman’s doctrine had gained supremacy and the traditional meaning of progress, as described by Ford and Branson, was beginning to erode.

The adverse consequences of shifting this focus to pure shareholder returns began to manifest when finance detached itself from its material foundations. The gold standard was abandoned. Paper claims multiplied faster than factories. The long view was eclipsed by short termism. Under this new order, profit became not evidence of service but an end in itself, detached from the real work of improving life. In this environment, the idea that business exists only to maximize returns didn’t merely describe reality, it accelerated the shift toward a more speculative, less grounded economy.

The most damaging consequence of the shareholder-first mentality is that it alters the time horizon of civilization. A factory or a technological breakthrough requires years of patient capital and discipline, whereas financial products and stock valuations can be manipulated in weeks. When the primary responsibility of an executive is to the shareholder rather than to the longevity of the enterprise or the quality of the product, the definition of efficiency changes. It ceases to mean the creation of better value and instead becomes the ruthless reduction of costs and the engineering of financial statements. The focus shifts away from how much utility a business creates to how efficiently they can be bought, sold, levered and exited. This mindset helped elevate the financier over the engineer, the spreadsheet over the workshop, earnings per share over tangible value creation.

Under pressure to generate quarterly shareholder returns, managers are incentivized to pursue “monetary distortion” rather than productive depth: they can cut R&D, shrink workforces, reduce sales and advertising expenses, outsource production and leverage debt to buy back shares. These actions may successfully increase short term earning per share and so spike the stock price, arguably satisfying Friedman’s objective, but what do they achieve in economic terms? We end up with a “statistical mirage” where the company appears to be improving based on market capitalization expansion, even as the underlying shareholder equity erodes and the prospects of the business decay.

This is the consequence of the Friedman doctrine: if growth is defined by financial output, then the purpose of enterprise naturally collapses into the pursuit of financial gain. We have a world where money, once a servant of purpose, becomes the master. Capital moves away from where it may be used most productively, and towards the most compelling narrative that appears to promise a fast-track to easy wealth (I’m looking at you crypto-currency!).

Societies progress when meaning accumulates, when effort builds something that endures. It isn’t about quick financial wins. We need to be willing to defer gratification so that capital, knowledge and innovation can compound over generations.

Friedman’s doctrine is not entirely wrong. It is a universal truth that a commercial enterprise cannot sustain itself without profitability. But Friedman’s theory is radically incomplete. It mistakes a symptom for a purpose. Profit is the reward for creating value, not the value itself. When companies forget this, they drift toward the extraction of existing wealth rather than the creation of new wealth (Michael Saylor, are you paying attention?).

A healthier understanding of enterprise would reconnect profit with purpose. It would recognize that businesses are not just machines for shareholder enrichment but institutions that translate imagination, skill and cooperation into real improvements in human life. Returns should follow from service, not substitute for it. When money measures contribution rather than dictating it, progress becomes real again: something built, something preserved, something passed on.

Sam Walton, Walmart’s founder, liked to remind people that there is only one real boss: the customer. If shoppers choose to spend their money elsewhere, everyone, from the chairman down, can effectively be “fired.” To keep that from happening, Walton believed a company must look after its employees and suppliers, because only then do the customers receive the best service. Shareholders are never the focal point, they were merely the beneficiaries of getting everything else right.

Looking at this through a different lens, if a company were to disappear tomorrow, customers would simply take their business elsewhere. Their day-to-day lives would barely change. The reverse, however, is far more consequential. If the customers disappear, the business collapses taking shareholder value with it.

The raison d’être of a company becomes clear: the customer is more important than the shareholder because the business owner’s prosperity depends entirely on the customer. Profit is an output, customer service is the input. That’s where the focus has to be.

In his early shareholder letters, Jeff Bezos correctly points out that the long‑term interests of shareholders are perfectly aligned with Amazon’s objective to “focus relentlessly on our customers”. He explains that doing the job right for customers today leads them to buy more tomorrow, brings in new customers and “adds up to more cash flow and more long‑term value” for shareholders.

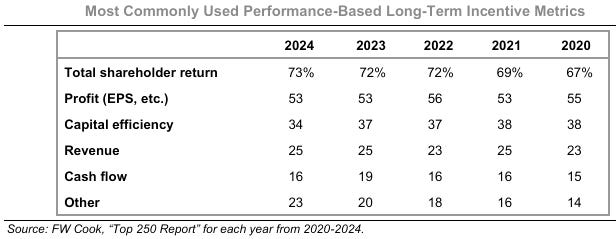

This is more important than it might seem. Take long-term incentive plans for senior executives as an example (see table below). They’re rarely designed to encourage the right behaviour. In most cases, total shareholder return, usually a blend of share price performance and dividends, is the dominant metric. Profitability typically comes next. Both measures push management to prioritize shareholders above everything else, even though long-term success starts with serving customers first.

Businesses that have achieved stand-out success operating in their given industry include Amazon, Walmart, Southwest Airlines and Costco. These firms all translate “customer first” into specific incentive metrics tied to customer experience — revenue growth, recurring revenue/subscription renewals, new customer acquisition, customer churn rates, customer satisfaction scores (net promoter scores) — all of which are within the control of management. Metrics are chosen to balance growth (sales) with efficiency (operating margins and ROIC), thereby avoiding a ‘growth at any cost’ mentality. This approach is far better than pegging remuneration to uncontrollable market sentiment (share price) or manipulable short-term targets (EPS).

Of particular note is that all four of these named companies actively deploy the ‘scale economics shared’ model. It is never about optimizing margins; the aim is always to delight, retain and win more customers.

These ‘golden threads’ that run through super successful companies are no coincidence. It is the economic manifestation of environmental convergence. In other words, through a process of trial and error, all have found this to be the optimal model. Investors would do well to look for these golden threads in companies before investing - why bet on a donkey when a stallion has proven itself to be more adept at winning races?

This is only one of many golden threads to look out for. If you wish to dig deeper, I explore this investment process in great detail in my book Fabric of Success, the Golden Threads running through the Tapestry of Every Great Business.

Before wrapping up, it is worth pointing out that the adverse consequences of the Friedman doctrine are not only economic but moral. When finance overtakes production and the pursuit of return overtakes the pursuit of service, society begins to lose the virtues that made progress possible in the first place. We live beyond our means. We produce the appearance of wealth and fewer sources of it. We mistake the appearance of prosperity for prosperity itself.

True progress is a “circle that endures,” built on the production of useful things and the stewardship of resources. By mistaking the symbol (money) for the substance (value), the single-minded pursuit of shareholder returns risks leaving us with a civilization rich in paper claims but impoverished in spirit and capacity.

Excellent piece on the purpose vs consequence framing. The Henry Ford quote really encapsulates the productio-first mindset that created actual value before financialization took over. What strikes me is how the "scale economics shared" model you mention with Costco/Amazon directly contradicts short-term EPS engineering because sharing gains with customers inherently compresses margins. I worked at a company that shifted from customer-centric metrics to TSR-based exec comp and watching that transition was instructive, decision velocity slowed becuz everything got filtered through "does this move the stock".

the goal of a "for profit" organization is... to make profit.

if that organization ownership is split to many pieces - it still needs to do the same thing. make profit. I think Friedman's "maximize shareholder return" is basically the same only from a different angle.

there are non-profit organizations - but very few really bring more value than their for-profit competitors (e.g. linux operating system).

as the sum of all those "for profit" organizations is basically the private sector, and private sector has been the main driver of prosperity in the mach of the developed world, i would not go and toss it over just yet :)

In my view, the core problem is not profit-seeking itself, but short-termism.

The short term mindset is probably more likely caused by management (who usually have shorter term outlook) than by shareholders.

what economists call "agency problem".

(chatgpt claims it was first introduced by Jensen, Michael C., and William H. Meckling (1976)

“Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure”)

I tend to subscribe to the view that management is typically short-sighted, unless they have a big stake in the business.

the bigger the management long term personal well-being is tied to the firm's long-term success the better the decisions tend to be.

It's not an insurance policy by any means, but if a dilema pops up, management is far more likely to take the right decision if it is not biased towards short-term stock price goal.