The End Of Accounting, Rely On It At Your Peril

The Path Forward For Investors | Ignore The Accountancy Clowns

Why does a company looks good on paper, but turn out to be a poor investment?

Why do conventional valuation metrics invariably sign-post the wrong companies?

Are corporate accounts a work of fact or fiction?

As investors, can we rely on the accountancy profession to guide us?

I attempt to answer all of these questions and more in this article.

Introduction

Never forget that accounting requirements are not designed to aid investors in decision making. They are primarily a means of quantifying the performance of a business for the tax man. Creative accounting is designed to mitigate tax liabilities and that, together with estimates layered on top of estimates, means that often they are less fact and more fiction.

“There is no question the leeway I have to report earnings as CEO of Berkshire is enormous.” Warren Buffett

As such corporate accounts, in their raw form, are of little value to investors and often they can be entirely misleading. I won’t labour the point, but if you would like to learn more, I highly commend the book “The End of Accounting and the Path Forward for Investors” by two eminent American university professors, Baruch Lev and Feng Gu.

I cannot overstate how different are the approaches of intelligent investors from those of the accounting profession. We see they earth as a globe, while they apparently believe that it is still flat!

Having said that, it is very important for investors to fully understand the way that accountants view the world. So I start with a brief overview through the lens of the accounting profession with a particular focus on the very poorly understood concept of Goodwill.

It may be a familiar concept, but it means something entirely different to an intelligent investor than it does to an text-book accountant.

To an Accountant: "Goodwill = the excess of the cost of an acquired company over the fair value of its identifiable net assets”

To an Investor: “Goodwill = the real value of the non-maintainable intangible assets, such as brand and reputation, that generate revenue and so create corporate value”

Do you really understand the difference and what it means to your investing decisions?

Most people don’t, so allow me to hold your hand and guide you through this critically important topic.

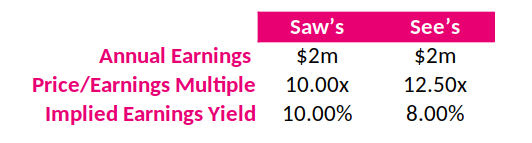

First, a quick test for you. Given the information in the table below, which company would you invest in?

Now read this article and let’s see if you change your mind by the time you get to the end.

What A Mess The Accountants Made!

The accounting treatment of Goodwill has changed significantly over the years.

In the early days accountants didn’t recognize Goodwill as an asset at all. It was just a cost incurred in acquiring an asset and expensed immediately. This resulted in turbulence to earnings caused by a huge extraordinary expense one year which disappeared in subsequent years. Accountants argued that the value of an acquired business was not entirely consumed in the year of acquisition, but instead endured for many years and so felt that the accounting treatment ought to reflect that.

So, in 1969, the accounting profession required Goodwill to be capitalized on the balance sheet and amortized over an arbitrary period of 40 years. I say arbitrary because it is impossible to predict the useful life of Goodwill or how its value will change over time and so to amortize it in a straight line over a fixed period is arbitrary. However, this change was intended to provide a more accurate picture of a company's financial performance.

By the 1980s, the accounting profession began to question the need to amortize Goodwill again. After all, Goodwill was an intangible asset that was not necessarily being consumed at all.

As a result, in 1993, the accounting profession changed its rules again and allowed Goodwill to be carried on the balance sheet indefinitely. Instead of amortization, Goodwill was to be tested for impairment at least annually.

Under the new test, if Goodwill was subjectively deemed to be worth less than its book value (an opportunity for managerial interpretation and bias), the negative difference became an impairment cost recognized in the income statement and the value of the asset was correspondingly written down on the balance sheet.

Not only was this subjective methodology unreliable, but it was also found to untimely. The erosion of Goodwill is never evident until well after the fact, meaning that the impairment cost was being recorded in the wrong accounting period which resulted in a misleading picture of the business activity of the company in question.

So the accounting profession effectively replaced one arbitrary approach with another.

A new complex impairment methodology was introduced together with disclosure obligations aimed at promoting transparency in relation to the process. This was designed to tackle the unreliability issue, but did little more than add cost and complexity to the process.

Now, the accountants are discussing the reintroduction of amortization of Goodwill, so they have gone full circle on the issue and are back to where they started.

What a mess!

And all the while the accountants fail to recognize the most important aspect of Goodwill from an investors perspective.

Ssshhh! This is the secret:

The Goodwill of a strong company doesn’t erode in value at all. Economic Goodwill increases in value and that is the magic ingredient to very favourable investment returns. This is particularly true in times of high inflation (just like today!)

So, let the accountants tie themselves in knots. We don’t care. We simply need to navigate through their mess and we’ll be just fine.

Economic Goodwill For An Investor

Assume a company, SuperCo Inc, has $20 per share of net tangible assets. Further assume that this is a strong business with a moat that is able to earn a great deal on its tangible assets, say $5 per share (25%).

With such economics an investor may be prepared to capitalize the business at 20x earnings, so ascribing it a value of $100 per share.

Now imagine that you bought the stock of SuperCo at $100 per share, paying in effect $80 per share for economic Goodwill (the value that you have paid above its net tangible value).

Based on this fact set, consider the following questions:

If the company continues to generate $5 per share of earnings ad-infinitum, is the value of your Goodwill eroding? I think not, all else being equal, it remains the same.

Now consider that sometime later you buy more shares in SuperCo at $120 each. The business still has $20 per share of net tangible assets and continues to generate $5 per share of earnings. Now the accountants will book the Goodwill element of this trade at $100, notwithstanding that exactly the same asset is already on your balance sheet from the earlier acquisition booked at $80. In other words, different purchase dates and prices have given us vastly different asset values for two pieces of the same asset!

Subsequently, SuperCo Inc doubles in size, increasing its tangible assets to $40 per share and, assuming no operating leverage, it achieves double its earnings as a result, now at $10 per share. If the company is still capitalized at 20x earnings net of debt, and the business utilized $20 per share of debt to increase its tangible asset base, then the economic value of the shares becomes $180 ($200-$20). What is the true “economic Goodwill” of the company now? I would argue that in respect of your initial purchase at $100, the Goodwill has increased from $80 to $140 per share. None of this is reflected in the corporate accounts on the balance sheet, but its very real to you as an investor and, if someone else acquired the business at this price, it would be recorded as Goodwill for them (try to reconcile that in your mind!)

This is the way that we investors view the world.

If we trusted investment decisions to the accountants, we would either believe that:

Under the Impairment Model: Goodwill is capped at $80 per share regardless of the prevailing economics of the business, meaning that the true economics of the business is not captured on the balance sheet; or worse,

Under the Amortization Model: the accountants will record $2 per share of amortization on the income statement every year for 40 years. Remember that we bought the shares in the company for $100, which was 20x net earnings of $5 per share. Well the accountants would show the net earnings at $3 per share ($5 less $2 amortization). That would imply that shares in SuperCo Inc are now only worth $60 rather than the $100 that we paid, or that the price that we paid was an eye-watering 33x earnings. Did we over pay? Or are the accountants misguiding us? I’ll leave you to decide.

Non-Cash Acquisitions

The situation becomes even more complicated when a business acquires another for stock rather than cash. I shan’t go into all of the detail here, but it would be remiss of me not to mention it.

When a company’s market capitalization (share price) changes, its not the value of the tangible assets that changes, its the economic Goodwill. Said differently, it is the premium over the value of tangible assets that the market is prepared to pay for the business which, if the business was acquired outright, would be recorded as Goodwill on the balance sheet.

So it stands to reason that when a company uses its own shares to purchase another business then it is, in essence, embarking on a Goodwill swap. To that end, when a company finds that its own stock is trading at very high multiples (in other words its Goodwill is being overvalued), it makes a great deal of sense to use that over inflated currency to acquire better valued assets.

If you believe that your Goodwill is being over priced, let us say that your business is trading at 40x earnings when 20x would be more appropriate, then you are effectively acquiring the Goodwill of the other company at a 50% discount.

Let’s put some numbers to this in order to demonstrate.

You recall that we acquired SuperCo Inc for 20x earnings (it was earning $5 per share and we paid $100). Now imagine that we are the CEO of SuperCo. The market becomes over exuberant and values SuperCo at 40x earnings, $200 per share when its economics remain unchanged. SuperCo is now showing an earnings yield of 2.5% ($5 earnings on a $200 investment) which doesn’t meet the hurdle rate of many intelligent investors. Now you spot BetterCo Inc which looks the way SuperCo looked previously. It also earns $5 in earnings per share on $20 of tangible assets and is trading at $100 per share in the market. That represents a 5% earnings yield. Much better. So what do you do? You could sell your holding in SuperCo Inc and use the proceeds to acquire BetterCo Inc, but you would be hit by a capital gains liability which is far from ideal. So why not use your stock to acquire BetterCo? It amounts to the same thing but without the CGT. You receive two shares of BetterCo for every one share of SuperCo, so you are effectively swapping $5 of earnings per SuperCo share for $10 of earnings per SuperCo share (2x BetterCo shares). Is that not equivalent to acquiring BetterCo shares at $50 each?

This is exactly what Henry Singleton and Warren Buffett have done on many occasions (click here to learn more).

On the example above, the accountants will book Goodwill on the acquisition of BetterCo at $80 per share, but the true economic Goodwill cost to you would have been $30. If BetterCo follows the same trajectory as SuperCo, then your gains will be magnified because of your lower entry price.

Warren Buffet and See’s Candy

In 1972, Warren Buffett bought See’s Candy for $25 million. At the time it had about $8 million of net tangible assets (including working capital). This level of tangible assets was adequate to conduct the business without the use of debt, and See’s was earning about $2 million after tax at the time.

Relatively few businesses are able to consistently earn the 25% after tax on net tangible assets that was earned by See’s, particularly with no financial leverage. It was not the fair market value of the inventories, receivables or fixed assets that produced the premium rates of return. Rather it was a combination of intangible assets: a wonderful brand and many loyal satisfied customers. This is what Buffett refers to as a consumer franchise, which is a prime source of economic Goodwill.

Buffett paid $17 million over net tangible assets for See’s and this was recorded as Goodwill on the balance sheet. More particularly, $425,000 was charged to the income statement annually for 40 years to amortize that asset (the arbitrary accounting rule at the time).

By 1983, after 11 years of such charges, the $17 million of Goodwill on the balance sheet had been amortized down to about $12.3 million. At this time See’s was earning $13 million after taxes on about $20 million of net tangible assets, so if capitalized at the same multiples, was worth $162.5 million (+550% in 11 years) . The economic Goodwill had thus increased not decreased. Despite showing at $12.3m on the balance sheet it was worth closer to $142.5 million.

See’s Goodwill may have disappeared if the business had collapsed for any reason, but it would never reduce in even decrements as straight line amortization implies.

However, if the business continued to prosper, the more likely scenario (as came to pass) was that the Goodwill continues to increase. Even if the business fails to grow, Goodwill would continue to increase in value due to inflation.

“We only buy it if we think [goodwill] is going to appreciate.” Warren Buffett

Inflationary Environments

Remember that Buffett acquired See’s when it was earning about $2 million on $8 million of net tangible assets. Buffett paid $25 million (capitalized at 12.5x earnings, an 8% earnings yield).

Assume that there was another company, Saw’s, that was also generating $2 million of earnings but on $20 million in net tangible assets. This company may only be worth the value of its net tangible assets, $20m (capitalized at 10x earnings, a 10% earnings yield), because its growth prospects are not as favourable as See’s (more on this later).

So, based on these assumptions, See’s has $17 million in Goodwill while Saw’s has no Goodwill.

Now let us imagine that inflation over a period is 100% (everything doubles). Both See’s and Saw’s would need to double their earnings to $4 million just to keep up with inflation (flat in real terms). To achieve this they need to sell the same number of products at double the price and, all else being equal, profits double.

But, as mentioned above, to make that happen net tangible assets, which includes working capital (receivables, inventories, etc) would also double. Maintenance CAPEX responds in the same way in response to inflation, it doubles.

So See’s needs to raise $8 million of new capital and Saw’s needs to raise $20m. Which business would you be happier owning?

Crucially, all of this capital investment being forced by inflation produces no improvement in rate of return of the business. The motivation for this investment is the survival of the business. Assuming that both raise the requisite capital, Saw’s has $40 million of net tangible assets earning $4 million annually and, remaining more capital intensive than See’s, continues to trade at 10x earnings, so it is worth $40m (zero Goodwill). In other words, its raised $20m of new capital to increase its market capitalization by $20m. That means that its shareholders would have gained only a dollar of nominal value for every new dollar invested.

By contrast, See’s, which now also earns $4 million, might be worth $50 million if valued at 12.5x earnings as it was at the time of Buffett’s purchase. So it would have gained $25 million in nominal value while the owners were putting up only $8 million in additional capital. That’s over $3 of nominal value gained for each $1 invested. Given the choice between owning See’s and Saw’s which would you rather be invested in? Now you see that See’s is far more desirable and why investors are prepared to pay more to own it. This is why it trades at a higher multiple to earnings.

See’s requires far less capital to grow than Saw’s. Looking at this through another lens, if Saw’s had only been to match the $8m of capital that See’s raised, it would have only grown 40% versus 100% growth at See’s.

Saw’s started with zero Goodwill and ended with zero Goodwill. See’s started with $17 million in economic Goodwill and ended with $34 million in Goodwill. This is where and why Buffett made a wonderful return on his acquisition of See’s.

“In most cases I would say the premium we pay above the net assets recorded on the books of the predecessor company overwhelmingly is for what we call economic goodwill. We don’t even look at the plants. We did not look at the plants of Scott Fetzer before we bought it. We did not look at the plants of H.H. Brown before we bought it. I have not looked at the plants since—I have never seen the plants at H.H. Brown. We don’t think in terms of appraising physical assets. We think in terms of economic goodwill. We believe that economic goodwill should all be placed on the balance sheet as a purchase. We even think that if we give stock that has greater intrinsic value, that it ought to be placed on at a higher price than market price.” Warren Buffett

Conclusion

Traditional wisdom – long on tradition, short on wisdom – holds that inflation protection was best provided by businesses laden with natural resources, plants and machinery, or other tangible assets ("In Goods We Trust").

But it doesn’t work that way. Asset-heavy businesses generally earn low rates of return – rates that often barely provide enough return to fund the inflationary maintenance CAPEX needs of the existing business, with little or nothing in the way of residual capital remaining to be invested in growth or for distribution to owners.

Also, the effective tax rate on cash flow is higher for asset-heavy firms. This is because the balance sheet cost of maintaining tangible assets increases due to inflation but is not immediatley tax-deductible. By the time it is depreciated, the real replacement cost (maintenance CAPEX) is significantly higher than the item labelled depreciation!

Similarly, since inventory and receivables are correctly included in tangible assets of the business, it is worth noting that firms investing in working capital get no break from the taxman on their opportunity cost.

Meanwhile, not only do asset-light firms enjoy lower tangible CAPEX needs, but they can sometimes benefit from free working capital funding.

A company’s working capital characteristics will have a significant effect on its ability to grow profitably and how it will navigates the turbulence of traditional business cycles. Nearly all firms operate with positive working capital. Simply put, they receive cash some length of time after they record revenue. A positive working capital balance represents invested capital that must be funded with debt or equity. As the company’s revenue grows, so do its working capital requirements and the amount of capital required. Working capital needs act as a drag on returns on capital and on the firm’s ability to produce profitable growth.

Some businesses are lucky enough to reverse this situation. They collect revenue for the sale of goods and services before paying their suppliers. As such, not only are inventories being funded by the supplier, but payables exceed receivables and so the business is effectively the recipient of free financing.

For a firm that operates with negative working capital, growth actually provides more capital to for allocation by the management. Said differently, instead of requiring incremental capital to support growth, the firm finds itself with excess cash which it may use to invest in fixed assets, perform acquisitions, or return capital to shareholders without sacrificing growth opportunities.

Just imagine running a business in which the more you grow, the more free cash you have to play with! Supermarkets are a perfect example. They receive cash today for goods sold in store, when they are not required to pay their suppliers for perhaps 90 days. So that represents a rolling 90 day free credit facility. The bigger the business becomes, the more free cash it has to play with.

This is not too dissimilar to the float that Buffett generates on his insurance operations and uses to grow Berkshire Hathaway.

Last, but by no means least, asset-light firms are often able to tax-deduct intangible investments by expensing them on the income statement upfront (software businesses are a perfect example). So the full tax benefit is received on an asset that requires little or not maintenance and yet becomes a recurring revenue stream assets.

The motto of this story is that while all businesses are hurt by inflation, those needing little in the way of tangible assets are hurt the least.

Finally, remember the test at the beginning of this article? Let’s explore the answer.

While I admit that you would need more information in order to make an informed investment decision, there is a great deal of information implied in what you have. Most amateur investors will immediately favour the stock trading at the lower earnings multiple as that provides the highest earnings yield. But an intelligent investor will ask why the market is ascribing a 25% premium to the value of company B and dig deeper.

Does this help?

Buffett chose Company B (See’s) back in 1972 and it was the correct decision because it was an asset light company with lots of economic goodwill.

Remember also that economic goodwill is not to be confused with accounting goodwill. While the accountants only value the goodwill on the balance sheet if the company is acquired, it has been there all along hiding in plain sight. The asset does not miraculously materialize simply because the company is acquired!

Consider Coca-Cola (another Buffett holding). It developed the recipe for its much loved drink in 1886. Now think about this:

The recipe was developed in-house and so accountants would expense 100% of that R&D immediately resulting in a big cost hit to the income statement in the year of development but no asset recognized on the balance sheet. Really? Is Coca-Cola not still making money from that recipe today, 150 years later? It is actually making far more money from that recipe today than it made in the early years so arguably this intangible asset has increased in value rather than having disappeared, but it is not deemed an asset of the company by accountants - go figure!

Even more bizarre is that if Coca-Cola had acquired the recipe from someone else for the same cost that it incurred in its R&D, then it would have been recognized as an intangible asset and accountants would amortize it over 15 years. So the same company with the same recipe at the same cost would be dealt with in two irreconcilable ways by accountants. The bottom line profit in 1886 would have been far larger because only 6.7% of the cost is included in the OPEX numbers in that year. However, for the next 14 years the bottom line would be smaller than had it developed the recipe in-house. The only consistency is that after 15 years the asset disappears despite still generating revenue for Coca-Cola 135 years later. Equally ridiculous.

Investors recognize economic goodwill regardless of the madness of the accountancy profession and this manifests itself in the difference between the market capitalization of Coca-Cola and the value of its net tangible assets. That difference is only recognized by accountants if and when the company is acquired by a third party. Really?!?

Smart CEOs recognize the hidden invisible value and capitalize upon it. They grow on a buy-and-build basis (serial acquirers). However, don’t invest in a business simply because it is growing by acquisition.

Most companies are run by people who are text-book accountants. The CFO will almost certainly be a qualified chartered accountant and very often the CEO has a similar background. We have already establised that accountants view the world differently to investors and this is why so many companies are poor capital allocators, particularly with respect to acquisitions. Investors in such companies should not necessarily expect wonderful returns.

The companies that do very well with acquisitions are those run by people that think not like accountants but like investors. Warren Buffett, Mark Leonard and Jeff Bezos are wonderful examples and all had foundations in the investment sector:

Jeff Bezos (successfully acquired over 130 companies) started his career on Wall Street in 1986, working at the asset manager D. E. Shaw & Co before founding Amazon.

Mark Leonard (successfully acquired nearly 600 companies) started at Ventures West, a Canadian venture capital firm before setting up Constellation Software.

Buffett (successfully acquired or invested in hundreds of businesses) worked from 1951 to 1954 at Buffett-Falk & Co. as an investment salesman and from 1954 to 1956 at Graham-Newman Corp. as a securities investment analyst before becoming CEO of Berkshire Hathaway.

One ought to ask, if the CEO and CFO of a company have no background or understanding of financial markets, equity investing or corporate valuations, are they best placed to be running a public company and allocating capital to acquisitions?

I’ll leave you to form your own view on that one. It will almost certainly need to be decided on a case by case basis, but it may be something that you had not previously considered.

Good luck with your investing. I hope that this article helped.