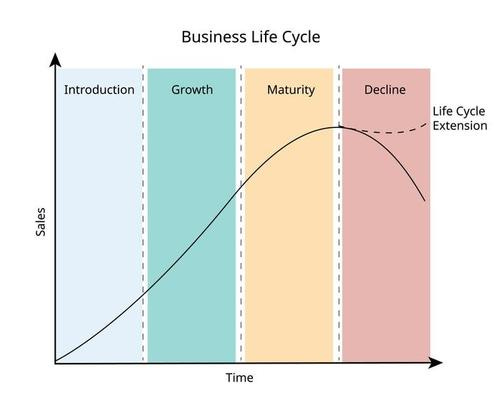

Many investors are looking down the wrong end of the telescope - they avoid investing in commodity based industries which they perceive to be in the final phase of their business life cycle.

They seem to have entirely missed the evidence that points to industry investment and industry profitability often being inversely correlated.

This framework, based around the capital cycle, suggests that it may be best to invest in companies from sectors where capital is being withdrawn and to avoid companies in sectors where investment is increasing rapidly.

This central focus on the supply-side dynamics of an investment stands in contrast to the practice of the broader investment community, which often falls prey to demand-side myopia.

Consider the tobacco industry as a wonderful example.

In 1964, the U.S. Office of the Surgeon General released a groundbreaking report definitively linking tobacco use to increased risks of lung cancer and chronic bronchitis. At that time, smoking was deeply ingrained in American culture: 43% of adults smoked, and over 500 billion cigarettes were sold annually. In the aftermath of the report, a wave of regulatory actions aimed at curbing tobacco use began. Among the most notable was the Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act of 1969, which banned cigarette and tobacco advertisements from television and radio.

Unsurprisingly, the percentage of adult smokers steadily declined, falling by a quarter - from 43% to 33% - in the 17 years following the Surgeon General's report. This trend marked the beginning of a structural decline in tobacco usage, which accelerated with the historic 1998 Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement (MSA). The MSA not only prohibited nearly all forms of tobacco advertising but also mandated that tobacco companies fund a multibillion-dollar anti-smoking campaign. Today, fewer than 12% of American adults smoke, and annual cigarette sales have plunged by 70% from their peak.

Given this backdrop, it may come as a surprise that one of the highest-performing investments over the past 60 years has been a tobacco company: Altria Group (MO). A $1,000 investment in Altria in 1970 would have grown to over $6 million today, representing an extraordinary 20% annualized return - far surpassing any global benchmark.

While Altria's recent share price performance has been more modest, the company has continued to outperform global indices over much of the past two decades. Its earnings per share have compounded at nearly 9% annually over the last decade, while consistently paying out 70% of earnings as dividends. This translates to an impressive mid-teens total return for shareholders.

How can such an outcome be explained?

Ironically, the near-total ban on tobacco advertising, which one might consider to be bad for businesses operating in this sector, was actually a huge benefit. It made it virtually impossible for new competitors to enter the market. Moreover, the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement imposes significant financial burdens on potential entrants, either through direct settlement payments or escrow requirements for future litigation. Together, these factors have created an oligopolistic market structure that grants tobacco companies extraordinary pricing power.

Warren Buffett once observed that a cigarette costs a penny to make, can be sold for close to a dollar, it’s addictive, and there’s fantastic brand loyalty. Not a bad industry in which to be operating as an oligopoly!

Over time, cigarette prices have skyrocketed - rising nearly 50-fold since 1964 - compared to a tenfold increase in the broader Consumer Price Index (CPI). While much of this increase is due to higher state and local excise taxes, these taxes ironically amplify tobacco companies’ pricing power. Since taxes constitute the majority of a cigarette’s final price, small price increases by manufacturers have minimal impact on demand but significantly boost profits. This dynamic has driven tobacco company operating margins from 15% in 1970 to nearly 60% today.

Despite declining cigarette volumes, these higher price points and expanded margins have allowed tobacco companies to generate outsized returns. Additionally, investor aversion to owning tobacco stocks has paradoxically benefited companies like Altria. Unloved businesses are typically undervalued, meaning an enhanced compounding of intrinsic value. Altria has taken full advantage, repurchasing tens of billions of dollars' worth of its own shares over decades well below intrinsic value, which is accretive to shareholder returns.

This is a phenomenon known as the "sunset industry effect".

This phenomenon is not unique to tobacco. Industries with structurally constrained supply can generate exceptional returns for well-positioned companies. The coal industry is another interesting example, which is currently offering a very favourable entry opportunity for the medium- to long-term investor:

Dirty Money | An Out Of Favour Industry

In a world captivated by cutting-edge technology and the relentless pursuit of the next big thing, it’s easy to overlook the quietly thriving industries right under our noses. While unprofitable AI ventures continue to attract massive investment despite burning through capital, a handful of savvy investors are turning their attention elsewhere. Eminent …

Price Dynamics

As supply decreases faster than demand, prices rise to restore market balance. In markets without readily available alternatives, demand remains relatively inelastic, allowing suppliers to raise prices to offset higher per-unit production costs resulting from reduced scale.

“Commodities usually die upwards, not downwards. They phase-out at higher prices than during earlier stages of their life cycle.”

There are many examples of this phenomenon in action. They include:

Leaded Gasoline: As countries phased out leaded gasoline, prices increased in some markets due to reduced production and continued demand from older vehicles.

Incandescent Light Bulbs: In some regions, prices rose as production ceased while demand persisted from consumers preferring traditional bulbs.

Coal: Despite global efforts to phase out coal, prices have experienced volatility and increases due to supply constraints and ongoing demand in certain markets.

Refrigerants: As certain refrigerants are phased out due to environmental concerns, prices have spiked for remaining stocks needed to service older equipment.

An Income Investment

Investing in sunset industries is primarily an income-focused strategy, as the capital value of these businesses often stagnates or even declines over time.

Charlie Munger once remarked that he would eagerly invest in Exxon Mobil (XOM) if management committed to ceasing all capital expenditures (CAPEX) and instead returning cash flows from existing oil fields directly to shareholders. In his view, such a scenario would make for an exceptional investment. However, oil companies typically reinvest cash flow into new projects, often with disappointing results when these ventures fail to meet expectations.

Occidental Petroleum (OXY), a company in which Berkshire Hathaway has made substantial investments, takes a different approach. Unlike many of its peers, OXY avoids speculative drilling and focuses on maintaining stable cash flows from its existing oil fields. This strategy allows the company to prioritize returning earnings to shareholders, effectively transforming its stock into a high-yield, low-risk asset—comparable to U.S. Treasuries, but with significantly higher returns.

For income investors, sunset industries can offer attractive opportunities, provided the companies are well-managed and prioritize shareholder returns over speculative reinvestment.

Conclusion

This "sunset industry effect" highlights the complex interplay of supply, demand, and market expectations in commodity pricing. It also presents a compelling investment opportunity for those willing to capitalize on the pricing momentum. In the twilight years of companies within these industries, rising prices often generate significant free cash flow. Since there is little need for CAPEX reinvestment due to the industry's decline, businesses typically return this surplus to shareholders through large dividends or stock buybacks, resulting in a windfall for investors.

Very good post. Can I translate part of this article into Spanish with links to you and a description of your newsletter?