Insider Ownership: Friend or Foe?

Insiders' share ownership is not the reliable indicator many believe it to be

Insider Ownership: Not as Reliable as It Seems

Most investors love the idea of management having “skin in the game”, but few apply much thought to the various forms of insider ownership - not all of them being good for shareholders.

In the award-winning paper, ‘Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure’1, first published in the Journal of Financial Economics back in 1976, its authors, Jensen and Meckling, advocate for equity compensation which they argue aligns interests with external investors.

Over time theirs has become one of the most cited papers in economics, finance, accounting, and corporate governance. Today, almost half a century later, I find myself citing the paper yet again as I delve into the nuance of this topic.

Many believe that insider buying and selling can serve as a reliable signal for investment decisions. After all, if insiders are buying, they must know something we don’t, right?

But here’s the twist: the evidence doesn’t back this up. In fact, it often points the other way - insider share ownership doesn’t reliably predict shareholder returns.

Weak Correlations

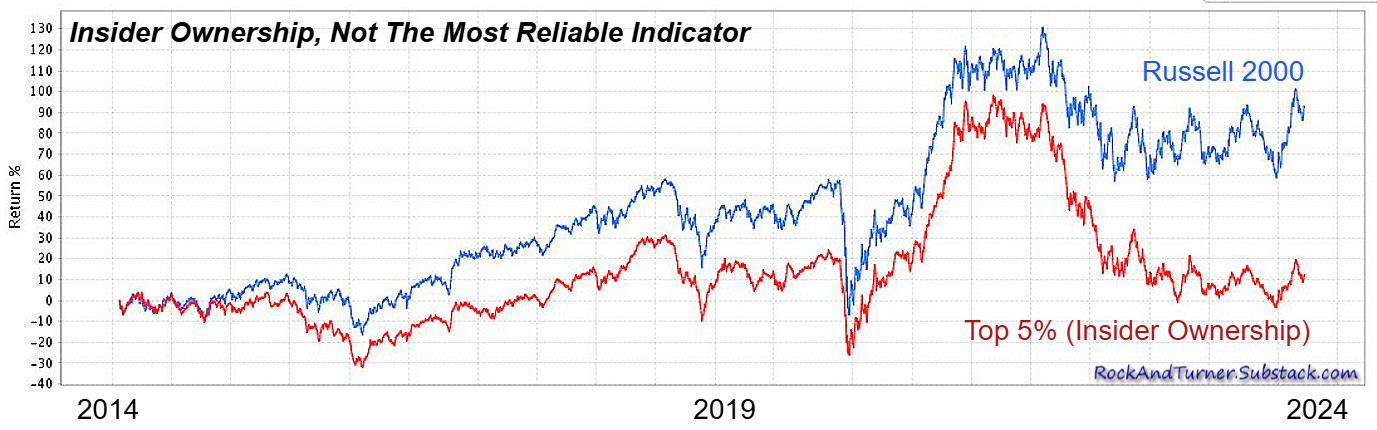

Insider ownership and shareholders’ returns are not well correlated at all. Empirical evidence suggests that the link is weak at best, with there being no more than a non-linear relationship.

If you had ranked the Russell 2000 index by percentage of insider ownership at each company, then invested in the top 5%, over the last decade you’d have made a meagre 12.3% total return (1.17% CAGR). Compare that to the index’s total return of 92.5% (6.77% CAGR), and the difference is stark.

Does this mean that investors ought to ignore insider ownership as a factor?

Absolutely not!

Uninvested management introduces a different set of issues.

What’s Wrong With Uninvested Management?

When management has no personal stake in the business, they become no more than employees. Their goal is to keep things stable so that the monthly paychecks keep flowing. They tend to either hoard cash or distribute earnings in the form of dividends, they avoid making bold decisions, and rather than taking risk in the pursuit of growth, they focus on maintaining the status quo. None of this is conducive to creating long-term value for shareholders.

This approach hurts a business.

A prime example is Japan where it is not uncommon for the leadership team to have no shares in the business that they manage. They see themselves as senior employees, following historic processes rather than being motivated to introduce progressive change. Most of the time external shareholders are viewed as little more than an inconvenience and largely ignored. The result? Japan’s Nikkei 225 has stagnated for over 30 years, with negative shareholder returns, largely due to unmotivated management.

Ultimately, this is an agency problem - conflicts of interest arise between managers (agents) and shareholders (principals) due to the separation of ownership and control.

Charlie Munger was always a firm advocate of creating the correct incentives. In this short video he describes why people perform better when they have skin in the game and agency problems are removed:

This "convergence-of-interest" hypothesis suggests that as insiders own more shares, their interests should align with shareholders, solving agency problems and boosting performance. It is a question of encouraging management to think like owners rather than perceiving themselves as being mere employees.

While this makes sense in theory, reality doesn’t play along. Empirical evidence shows that higher insider ownership doesn’t consistently lead to better outcomes for investors, especially when insiders have too much ownership.

When Too Much Skin in the Game Backfires

Evidence suggests that high levels of insider ownership doesn’t always mean better performance. In fact, beyond a certain point, too much insider ownership can do more harm than good.

So far we have discussed encouraging management to adopt an owner’s mindset through taking an ownership stake in the business. But what happens when those leading the business are already the majority owners? Now the problem inverts. Now it becomes a question of encouraging owners to adopt a management mindset.

When the ownership of insiders is so large and their wealth so great, they are no longer motivated to create more wealth for themselves - theirs becomes a mission of preserving capital and focusing on income generation instead.

Ironically, as was the case for uninvested management, the incentive is to become risk-averse, albeit for different reasons. Why risk the allocation of capital to grow the business when it could simply be paid out as a fat dividend instead?

Excessive insider ownership is especially problematic in family-run businesses, particularly those held through trusts across generations. Founding families often prioritize income generation over long-term growth, using dividends to maintain lavish lifestyles instead of reinvesting for future gains.

This approach can create a significant conflict of interest: external shareholders want growth, but insider families focus on preserving wealth, often at the expense of company performance.

When self-serving managers prioritize their own interests over maximizing shareholder value, this is known as the ‘entrenchment effect’. Other manifestations may include resisting mergers and acquisitions that could benefit the company but dilute their influence and control over the business.

Not all companies with majority insider ownership are risk averse. Sometimes the opposite is also true and equally alarming for shareholders.

When the CEO has such a large ownership stake that he has majority voting rights, external shareholders have little or no influence over the direction of the company. A case in point is Meta (formerly Facebook), where CEO Mark Zuckerberg's outsized control has enabled massive spending on projects like the Metaverse - widely criticized as vanity investments - which have destroyed shareholder equity.

Either way, when insiders have majority ownership, it all too often acts as a drag on performance. Different stakeholders are pulling in different directions - there is no way to balance the wants and needs of external investors and those of the controlling insiders.

This means that for investors, the size of a company’s public float is crucial. A broad, diverse ownership base ensures external shareholders can influence management decisions. In contrast, concentrated insider ownership gives insiders unchecked power, allowing them to ignore shareholder opinions.2

The Goldilocks Effect: Finding the Sweet Spot

Research backs up the idea that insider ownership works best when it’s neither too little, nor too much, but just the right amount.

A 2003 U.S. tax cut on dividends provided a unique opportunity to study this3. The tax rate was slashed from 35% to 15%, meaning that shareholders enjoyed a 31% uplift in the income being received from their ownership stake. This made the equity stake held by insiders instantly far more valuable - but how would that impact on the performance of management?

The results?

Businesses where managers owned very few shares didn’t see much change in corporate performance. The financial incentives remained weak; even after the tax change management had too little at stake to care much about performance.

Companies with high levels of insider ownership didn’t experience much change to corporate performance either. Managers were already heavily invested and independently wealthy, with no intention of cashing in their investment, so had little or no motivation to work hard at growing the business further.

Those operating in the sweet spot had management with enough stake to care about performance, but not so much that they became indifferent to the effect of the tax cut.

The relationship between insider ownership and corporate performance follows a Goldilocks principle: not too high, not too low, but just right. For investors, striking this balance is key to finding companies where leadership is motivated to deliver strong results without falling into the traps of risk aversion or entrenchment.

How Insiders Become Shareholders Really Matters

The way senior management becomes shareholders in a company - whether as founders, through open market purchases, or via stock-based compensation - is the other factor that has significant implications for investors.

Management with a founder mindset should be focused on increasing their own wealth by making the share of the company that they already own more valuable - not by granting themselves more equity over time. If they have faith in their ability, they should show that by investing more of their personal wealth in increasing their stake of the company that they are managing - not by seeking risk-free handouts at the expense of external investors.

In the Berkshire Hathaway owner’s manual it says, “In line with Berkshire's owner-orientation, most of our directors have a major portion of their net worth invested in the company. We eat our own cooking… [we] cannot promise you results. But we can guarantee that your financial fortunes will move in lockstep with ours… We have no interest in large salaries or options or other means of gaining an "edge" over you.”

Founders own shares by virtue of having founded the company. They tend to be passionate about achieving success and see it as their life’s work. They increase their wealth by enhancing the value of what they already own and, in so doing, create wealth for others.

Amazon, for instance, is a businesses built on a long-term vision and the excellent ethics of its founder. Let’s hear what Jeff Bezos says on the subject:

This kind of insider ownership is high quality. It’s exceptionally rare. Shareholders who find businesses with CEOs that think in this way should jump on the fast moving train and enjoy the ride.

In contrast, when career executives receive shares as part of their pay package, they view them as a cash equivalent, albeit subject to a vesting period. They’re ready to sell at the earliest opportunity as the chart below demonstrates.

This “seller mindset” of insiders in relation to their stock holdings is the exact opposite of how investors think. External shareholders buy the stock with a long-term view, aiming to hold it for growth and perhaps dividend income - a “buyer mindset”. So, despite the claims from corporate management who advocate for stock-based compensation, it rarely, if ever, aligns management’s interests with that of external shareholders’.

Stock-based compensation is tantamount to a transfer of wealth from external shareholders to insiders - a quasi management tax on investors. To make matters worse, management attempts to hide the dilution from stock based compensation by buying shares on the open market to offset dilution. So they are gifting themselves shares, usually at a discounted price, and then reducing the share count through buying at a higher price on the open market, typically well above intrinsic value - a ‘buy high, sell low’ strategy that only a fool would countenance. This kind of activity destroys shareholder equity, but very few investors seem to notice. Big tech companies are the worst offenders with Apple and Google being serial offenders.

The story doesn’t end there. Career CEOs hop from one public company to another on average every four years.

This results in the wrong incentives. Their bonuses and stock options are tied to short-term metrics like earnings growth or share price. This encourages behavior that boosts numbers in the short term but damages the company’s future.

Some common tactics include:

Cutting R&D or advertising to inflate profits.

Stock buybacks to make earnings-per-share look better.

Selling off core assets for a quick cash boost.

This happened under Lou Gerstner at IBM and Sir Terry Leahy at Tesco, where short-term wins eventually led to long-term harm. The problem? By the time shareholders realize the extent of the damage done, the CEO has already cashed out and moved on.

Stock-based compensation is the wrong kind of insider ownership, with only one exception. If a startup is being boot-strapped and has sufficient cash flow to secure the talent it needs, then it should offer sweat-equity in lieu of cash salary. It should never be given by a cash generative business to unnecessarily supplement a wonderful salary.

Companies need to incentivize leaders to focus on the future, not just their bonuses. Aligning CEO incentives with long-term company goals is crucial for sustainable growth. They should focus on creating a culture where leaders think like owners and prioritize long-term value creation over short-term gains.

Very few companies recognize this challenge, and still fewer seek to address it. However, there are a small number of businesses with exceptional stewardship which have found ways to align incentives with long-term success.

These are the companies that investors ought to seek out. This is the best form of insider ownership.

These exceptional businesses require executives to purchase shares of the company on the open market in the same way that external investors do. They require all insiders to have a significant part of their personal wealth invested in the business that they are managing - so their fortunes move in lock-step with those of external investors. This approach fosters a sense of ownership and commitment to long-term growth. Both insiders and external investors adopt a ‘buyer mindset’.

Additionally, when an insider is happy to invest with his own money, it not only shows confidence in his own leadership ability, but it aligns his interests with all other shareholders. Examples of companies that follow this model include Constellation Software and Berkshire Hathaway, and their corporate results speak for themselves.

An Alternative Approach To Insider Ownership

Some forward-thinking companies avoid insider share ownership altogether. Their reasoning? Share prices can be unpredictable, influenced by market sentiment, economic swings, or geopolitical events. When the stock price drops, it can distract and demoralize insiders, especially if a big chunk of their remuneration is suddenly wiped out.

The share price is, to a large extent, a red-herring. It was John Maynard Keynes who observed that the stock market often remains irrational for extended periods.

So instead of tying management rewards to stock prices, companies like Enterprise Rent-A-Car focus on broader metrics. It ties its management incentives to metrics including profits, customer retention, and revenue per customer. This encourages leaders to prioritize long-term customer loyalty, which ultimately fuels sustainable growth.

Similarly, Howden Joinery in the UK and Mainfreight in New Zealand have successfully implemented models that reward managers based on the company’s overall performance rather than stock-based compensation.

To foster long-term success, companies need thoughtful compensation strategies that align leadership with the business’s future. Whether through open-market share purchases, profit-sharing models, or creative metrics like customer retention, the goal is the same: build a culture where leaders think like owners and prioritize sustainable growth over short-term gains.

When the business does well, insiders are rewarded appropriately, while external shareholders benefit from rising share values and potentially higher dividends. It’s a win-win that fosters lasting success.

Insider Buying and Selling: Not Always a Reliable Signal

Executives selling shares might just be about covering tax liabilities or paying for big ticket items such as a new home, a wedding or a university education.

The legendary Magellan Fund manager Peter Lynch once said, "Insiders might sell their shares for any number of reasons, but they buy them for only one: they think the price will rise.”

Is Lynch correct? The word ‘think’ is the operative word.

When an insider buys on the open market, it’s tempting to see it as a clue for external investors. But in reality, it’s rarely a meaningful signal.

As external investors, we look at companies across industries and geographies. We have the freedom to move money to where we see the best opportunities. Insiders, on the other hand, are deeply entrenched in their own company and industry. Their perspective is narrow - like a horse wearing blinkers.

When an insider decides to buy shares in the business that employs him, perhaps inspired by the exuberant rhetoric at a management meeting, how likely is it that he’s actually conducted any deep analysis, like comparing the company’s value to that of its competitors? Was the decision a thoughtful one, considering the opportunity cost of not investing elsewhere, or were they influenced by the comfort of sticking with what they know?

When it comes to buying shares, most corporate executives don’t have expertise in valuing companies. A software CEO, for instance, is likely more skilled in coding than in corporate finance. This lack of financial acumen means their trades often reflect gut feelings or recent price trends, rather than informed investment decisions.

Insiders are also acutely aware that their trades are scrutinized by the market, which can further complicate their decision-making. When bonuses are benchmarked against the share price, a common mistake made by remuneration committees, it may be possible for the CEO to influence market sentiment by placing some relatively small insider buy orders. The wrong incentives have a habit of encouraging the wrong behaviour.

As such, most insider trades are often influenced by exogenous factors and are entirely unreliable indicators for external investors.

Research has shown that Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) where insiders are net buyers tend to underperform substantially throughout the 36-months post-IPO period. Rather counter intuitively, the study found that IPOs with net insider selling actually generated positive returns, while those with net insider buying underperformed4.

Other studies have found that buying activity of insiders is often inversely related to future stock returns5.

The only time that insider activity is a solid indicator is in a situation where you have a CEO with a solid grasp of corporate finance (a rare trait) and so only allocates corporate capital to the repurchase of shares when they are trading below perceived intrinsic value. Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway is, once again, the best example. This kind of activity is certainly a positive signal for investors.

Unfortunately, most buybacks don’t follow this logic. Many are executed at inflated prices simply to offset dilution from stock-based compensation. This is certainly not a positive signal - more of a red flag.

Conclusion

To wrap things up, let’s revisit the famous Jensen and Meckling paper. First, a quick clarification: shareholders often think of themselves as partial owners of a company, but legally, that’s not quite true.

A company is a separate legal entity - a "legal person" with its own rights and obligations. Shareholders don’t own the company itself; they own rights tied to their shares, like voting power, dividends, and a claim on assets if the company is liquidated.

In this context, Jensen and Meckling describe a corporation as a "legal fiction" that serves as a complex web of contracts between stakeholders. Behind this setup are vulnerable shareholders who depend on management’s competence and integrity - and the incentives that drive them.

For investors, it’s important to look beyond insider trades and focus on the broader picture. The ideal setup? Modest executive salaries, insiders invested in approximately 30% of the company, and shares purchased on the open market. Unfortunately, companies like Berkshire Hathaway that embody this model are rare.

In 1979 the inaugural Leo Melamed Prize, attributed by the University of Chicago’s Graduate School of Business (GSB) for outstanding scholarship by business school teachers, was awarded to two former Chicago students, Michael Jensen and William Meckling for their 1976 paper, “Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure,” Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360.

Xing Li and Stephen Ten Sun (2014): “Managerial Ownership and Firm Performance: Evidence From the 2003 Tax Cut”

Demsetz, H., 1983. The structure of ownership and the theory of the firm. Journal of Law and Economics 26, 375–390.

Demsetz, H., Lehn, K., 1985. The structure of corporate ownership: causes and consequences. Journal of Political Economy 93, 1155–1177.

Demsetz, H., 1986. Corporate control, insider trading, and rates of return. American Economic Review 76, 313–316.

Morck, R., Shleifer, A., Vishny, R., 1988. Management ownership and market valuation: an empirical analysis. Journal of Financial Economics 20, 293–315.

McConnell, J., Servaes, H., 1990. Additional evidence on equity ownership and corporate value. Journal of Financial Economics 27, 595–612.

Loderer, C., Martin, K., 1997. Executive stock ownership and performance: tracking faint traces. Journal of Financial Economics 45, 223–255.

Himmelberg, C., Hubbard, R.G., Palia, D., 1999. Understanding the determinants of managerial ownership and the link between ownership and performance. Journal of Financial Economics 53, 353–384.

https://www.citystgeorges.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/354387/Hoque-Lasfer-2014-Insider-Trading-Long-Run-Performance-IPOs.pdf

https://www.storre.stir.ac.uk/retrieve/27d61b0e-2481-48b6-b562-71940846d333/Insider%20trading%20and%20future%20stock%20returns.pdf