Sometimes, the more you work, the less you achieve. Working harder is not necessarily working smarter. This is particularly true when it comes to the art of investing.

In the modern world, there’s a prevailing obsession with short-term gains, driving investors to hop from stock to stock in pursuit of momentum. This fixation has far-reaching consequences, creating a butterfly effect that distorts investment strategies, fund management approaches, and corporate decision-making. As investors demand quick returns, fund managers chase transient trends, while corporate leaders face mounting pressure to deliver immediate results. The entire system is misaligned, with incentives pointing in the wrong direction.

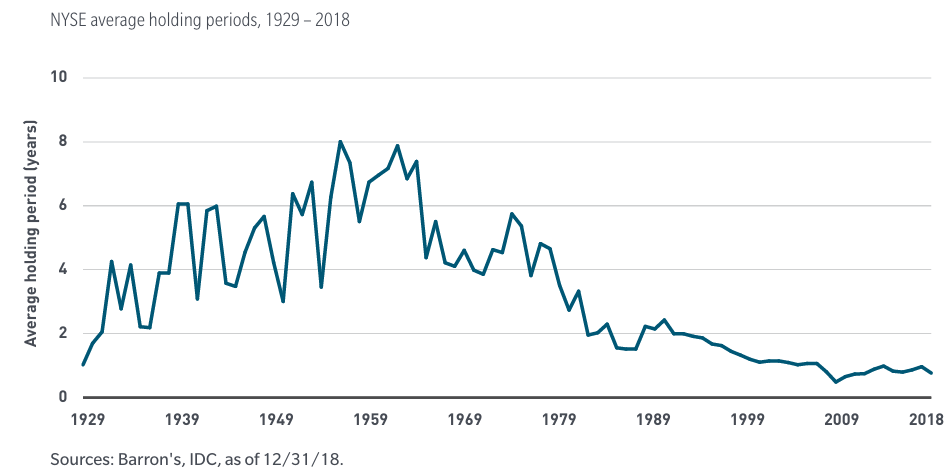

This is no academic debate, the facts and figures speak for themselves. In the U.S. during the 1950s, the average holding period for corporate stocks was 8 years. Fast-forward to 2020 and it’s a mere 167 days. Equities are being treated more like lottery tickets than stakes in tangible businesses.

This ‘Subconscious Myopia’, a term coined by Andrew Haldane, former chief economist of the Bank of England, undermines long-term potential and leaves many investment portfolios falling short.

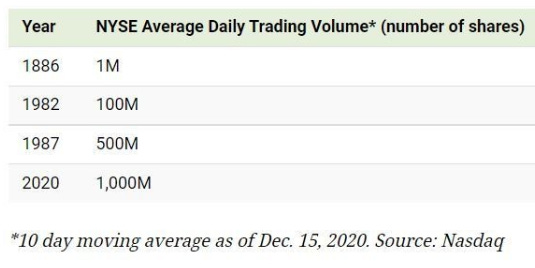

Shorter holding periods lead to a surge in transactions, benefiting sell-side firms that profit from selling analysis and collecting transaction fees. However, this increased activity comes at a cost, ultimately hindering investor performance.

Why do so many investors fall into this trap, and what lessons can we learn from those who buck the trend?

Logic suggests that one should buy low and sell high - but what does this really mean? When is ‘high’ achieved?

The challenge lies in timing the market, which is far from an exact science. In fact, many investment professionals advise against trying. Why? Because successfully timing the market requires being right twice: knowing not only when to buy but also when to sell. Even seasoned investors find this incredibly difficult, and getting the timing wrong could be costly.

Research comparing short-term portfolio managers with long-term buy-and-hold investors highlights clear differences in outcomes and strategies.

Short-term managers incur frequent transaction costs, they face expenses for ongoing research and strategic portfolio adjustments, and struggle with the complexities of trade timing. The outcome is a continual cycle of ‘buy, sell and repeat’, which negatively impacts returns.

On the other hand, buy-and-hold investors enjoy several advantages. They benefit from lower transaction costs as they avoid frequent trading, and from multiplicative compounding1 of gross returns due to tax deferrals. Over time, this approach results in far higher returns, as it prioritizes long-term growth and avoids reacting to short-term market fluctuations.

Managers like Nick Train at Lindsell Train, Richard Pease at Crux (now part of Lansdowne Partners), and James Anderson at Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust, differentiate themselves through a deep and intimate understanding of the companies they invest in, maintaining a highly concentrated portfolio, which contains a smaller number of long-term high-conviction positions. These managers actively engage with the companies they invest in, building long-term relationships with management teams.

None of this is possible when the portfolio manager constantly churns his holdings, an approach that echoes the Theseus Paradox.

In Greek mythology the Minotaur was a fearsome creature, half-man and half-bull, that lived in the Labyrinth - a complex maze. The custom was for seven young men and seven young women to be sent into the Labyrinth as a sacrifice to appease the Minotaur. However, Theseus objected to this horrific ritual and so entered the Labyrinth, slayed the Minotaur and rescued the young men and women, returning them to Athens on his ship.

Subsequently, Athenians would celebrate the anniversary of Theseus’ victory by taking his ship on a short voyage. However, over the years, the ship's wooden parts decayed and were replaced. After several hundreds of years of maintenance, if every piece of the ship had been replaced, one after the other, was it still the same ship? This is the paradoxical question that has prompted much philosophical debate.

A similar question can be posed in relation to an investment portfolio. If all the individual assets within a portfolio are frequently replaced, is it still the same portfolio?

Some may argue that the portfolio's purpose, risk profile, and target allocation are what define its identity rather than the specific assets it holds. But how likely is it that an investor is able to achieve extraordinary results on a consistent basis with a series of entirely different portfolios? Yet this is what most try to achieve - the impossible dream!

Eminent investor Philip Fisher, who heavily influenced Warren Buffett’s investment approach, advocated an investment philosophy built on finding the handful of companies that can grow at a sustainably high rate over long periods of time. They are rare, as we discovered when studying Hendrik Bessembinder’s findings that only 4% of stocks account for the outperformance of the market, so when such a company is found, buy it, and hold on tight. These businesses may trade at a premium, which is why Charlie Munger always said that it is better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price, than it is to buy a fair company at a wonderful price.

‘If you are in the right companies, the potential rise can be so enormous that everything else is secondary.’

Phil Fisher

If an investment thesis did not work out as anticipated, or if circumstances changed materially, then Fisher would sell. In all other circumstances he would simply hold indefinitely, even if the stock has risen to the extent that it looked over-valued. He explained that if the only thing that changed for the business is the stock price, then selling a rarity makes no sense. It’s better to hold on and suffer a little turbulence along the way than to sell and miss its true compounding potential.

Fisher explained that every $1,000 that he invested in Motorola in 1957 grew over time to be worth $1,993,846. It wasn’t linear, there were ups and downs along the way, but it was fundamentally a great business that was worth holding. He pointed out that had it been a private unlisted company, he would never have considered selling it - so he viewed its public company status and the stock market as nothing more than an unwelcome distraction to be ignored.

‘Our favorite holding period is forever.’

Phil Fisher

Fisher explained that had he sold Motorola because he thought it was overpriced at any time along the way, the chances are that he would not have known when to get back in, and so would have missed a tremendous profit.

A subtle nuance that many miss is that the opportunity cost of selling a compounder is almost always too high because the real benefits of compounding come at the tail end of a really long run. To exemplify, if you have a penny and manage to double its value every day, by the 30th day it will have grown to be worth $5.4 million. Yet half of that gain was made on the final day, and 75% of it was made in the final two days.

This explains the observation made by Morgan Housel, in his book ‘The Psychology of Money’, that 99% of Warren Buffett's net worth was amassed after he turned 65 years old.

Every time a portfolio is rebalanced, the investor incurs costs that lower the total compound returns that his portfolio will achieve. These costs include frictional transaction expenses, crossing the bid/ask spread for both the sale and subsequent reinvestment, and tax liabilities on any realized gains. The opportunity cost that flows from this interruption of compounding is far larger than most imagine.

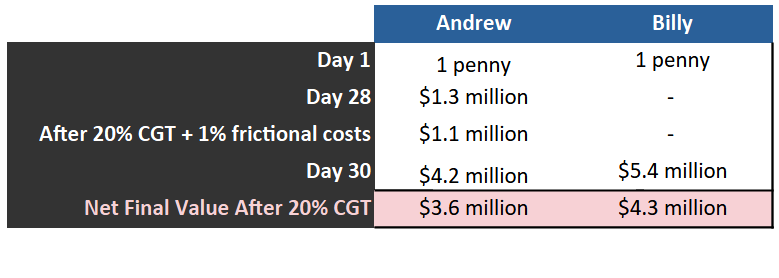

To illustrate the potential harm caused by frequent portfolio adjustments, let’s consider two hypothetical investors, Andrew and Billy. Both start with a penny and invest it in an asset that doubles in value each day. For this example, we assume a capital gains tax rate of 20% and frictional costs of 1% for selling an asset and reinvesting the proceeds:

On the 28th day Andrew decides to sell, at which point he crystalizes $1.3 million.

Billy decides to sit on his hands and do nothing, enabling his penny to continue compounding.

Now let’s assume that Andrew immediately decides reinvest his proceeds of sale to acquire a different asset with exactly the same ability to double in value each day. On the face of it, he should be at no disadvantage, but he is.

By selling his first asset he finds himself subject to 20% capital gains tax and he incurs another 1% in frictional transaction costs, so he now only has $1.1 million to reinvest in the second asset.

Two days later, both Andrew and Billy decide to liquidate their positions.

Andrews receives $4.2 million which, after capital gains tax, nets him $3.6 million.

Billy, on the other hand, finds his penny had grown to $5.4 million which, after tax, nets him $4.3 million.

Andrew’s tinkering with his portfolio carried an opportunity cost of 19.4% - an expensive mistake, and he only tinkered with his portfolio once. Just imagine how much worse it would have been had he regularly been buying and selling.

As shown in the example of Andrew and Billy, short-term tinkering creates frictional costs that significantly reduce gains. To achieve the same final net valuation, Andrew would need much higher annual returns than Billy, making his task unnecessarily difficult.

As I stated at the beginning of this piece, sometimes, the more you work, the less you achieve. Working harder is not necessarily working smarter.

The General Mills pension fund illustrates the power of disciplined, long-term investing. Annually, it consistently ranked in the second quartile, never exceeding the 27th percentile or dropping below the 47th. Yet, over 14 years, it ranked in the 4th percentile overall. This success came from avoiding the pitfalls of chasing short-term returns and minimizing frictional costs by maintaining a buy-and-hold portfolio. The fund manager’s strategy required far less effort than that of highly active managers, as minimal trading was involved. Remarkably, he never needed to achieve top-percentile performance in any single year to secure top-percentile results over the long term. The lesson is clear: wealth is built by achieving strong long-term averages, which can be accomplished through consistent, above-average performance.

This explains why Warren Buffett, who has sat on his American Express investment for 60 years and his Coca-Cola position for 35 years, has far superior returns to the average fund manager who constantly tinkers with his portfolio. Buffett explains it himself in this short video:

If one were only permitted to make 20 investments in a lifetime then not only does that shift one’s perspective on what to buy, it would also significantly influence one’s thinking around when is the best time to sell.

This view was reinforced in Buffett’s 2022 shareholder letter in which he stated, “In 58 years of Berkshire management, most of my capital-allocation decisions have been no better than so-so… Our satisfactory results have been the product of about a dozen truly good decisions – that would be about one every five years…”

Regarding position sizing, he explained that for a long-term investor, weightings tend to take care of themselves. Using his Coca-Cola investment as an example, he noted that over the 30 years he had held it, its value had increased roughly 20-fold. Additionally, Coca-Cola had increased its annual dividend by a factor of 10, meaning his initial investment had been repaid many times over. Today, the position accounts for approximately 5% of Berkshire Hathaway’s net worth. He contrasted this with a hypothetical scenario in which he had made the mistake of investing in a high-grade 30-year bond instead of having purchased Coca-Cola stock. Holding the bond to maturity over the same period would have generated neither capital appreciation nor an increase in income. Consequently, it would have proven to be a poor investment, shrinking in significance to just 0.3% of Berkshire Hathaway’s current net worth.

“The lesson for investors: The weeds wither away in significance as the flowers bloom. Over time, it takes just a few winners to work wonders.”

Warren Buffett

Berkshire’s portfolio, a mix of private and public businesses, has a median annual portfolio turnover rate of around 4%, but it has been as low as 2.1%, suggesting an average holding period of greater than 25 years. Compare this to the average turnover rate for large managed equity funds, which typically ranges from 30% to 60%, suggesting an average holding period of only 2 - 3 years.2 It doesn’t take a genius to work out how Buffett has outperformed almost all other investors over the course of his 65+ year career?

To provide some balance, it’s important to acknowledge that shorter-term trading strategies do have their place. These strategies may focus on special situations or micro-cap stocks experiencing rapid growth in their early stages. However, the value an investor can capture in these cases is typically short-term and opportunistic, requiring them to constantly move from one opportunity to the next. This is no small challenge, as identifying such opportunities is inherently difficult, and the need to repeatedly find new ones makes it an even more daunting task. Over the long term, this approach tends to be far more complex and less reliable for wealth creation than simply buying and holding high-quality companies.

In conclusion, investors should focus on selecting exceptional businesses and allowing them to grow over extended periods, understanding that true wealth accumulation happens through patient, strategic investment rather than frantic trading. It’s less about constant activity and more about patience, discipline, and strategic long-term thinking.

Multiplicative compounding causes the distribution of long-term individual stock returns to become extremely asymmetric with a very positive skew, and it is this which causes the best fund managers to outperform: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Delivery.cfm/SSRN_ID3835813_code1278716.pdf?abstractid=3835813&mirid=1&type=2

Dr David Kass, Finance Professor at Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland.