The 4% of Companies Worth Holding

Which Are They? Do You Own Them? Is Now The Time To Buy Them?

Prepare To Be Challenged

Have you ever found yourself in a situation where you thought you fully understood something, only to discover new information which completely derails your prior understanding?

Well, this article is likely to knock you off balance in relation to your perception of the stock market.

Over most of the last century, the U.S. stock market has delivered average annual total returns (including dividends) of about 10%. While these returns were not evenly distributed across all listed companies, the market as a whole has been largely predictable. However, over the last 10 -15 years, everything has gone haywire. Consider the following:

extraordinary monetary policies driving real interest rates below zero and expanding money supply causing asset bubbles,

a growing focus on Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) factors that have introduced non-financial dynamics into corporate valuations,

a wave of shell companies with no business and no earnings known as SPACs (special purpose acquisition vehicles) that attract investment capital,

retail investors wielding newfound power via social media collectives with the ability to push “meme stocks” to irrational highs and to drive cryptocurrency euphoria,

passive investing displacing active as the dominant form, and

unprecedented instances of companies manipulating their own stock price.

It’s hardly surprising that the market has become entirely unpredictable and irrational.

"If you're not a little confused by what's going on, you're not paying attention."

Warren Buffett

So what is going on? More particularly, what does it mean for your investment decisions? Where should you be putting our money to work?

This article seeks to make sense of it all, pulling on a number of sources and data spanning back well over a century.

Let’s begin the journey with Professor Hendrik Bessembinder of Arizona State University, who wrote a research paper entitled, "Do Stocks Outperform Treasury Bills?”1 An innocuous question if ever I saw one, but his findings were not what I had expected.

Based on almost a century’s worth of U.S. stock market data, his study provides a nuanced view of stock market performance that challenges some common perceptions about investing. This not only raises questions in relation to portfolio management, but may also shed light on the recent success of passive investing.

Bessembinder made two key findings, one expected and the other a huge surprise.

As expected, in line with conventional wisdom, the stock market as a whole does outperform low-risk investments like Treasury bills;

The surprise, however, was that while the overall stock market has historically provided strong returns, the majority of individual stocks have not outperformed Treasury bills. Instead, the positive performance of the market as a whole is driven by a relatively small number of extremely successful stocks.

Bessembinder certainly didn’t cherry pick data to exaggerate his findings - instead he used all data on listed companies that have appeared in the CRSP2 database since 1926.

He found that in terms of lifetime dollar wealth creation, the best-performing 4% of stocks account for all of the outperformance. The remaining 96% of stocks collectively do no better than Treasury bills, while 57.4% had lifetime buy-and-hold returns (including dividends) that underperformed returns on one-month Treasury bills. Even more shocking was the discovery that over half of the stocks delivered negative lifetime returns.

Concentration Of Wealth-Creation

One of the most striking aspects of Bessembinder’s study is the tiny number of company stocks that are responsible for all of stock market wealth-creation. (The term “wealth-creation” is defined as the accumulation of market value in excess of the value that would have been obtained if the invested capital had earned one month Treasury bill interest rates.)

Of the 25,300 stocks in the CRSP database in the period from 1926 to 2016, total wealth-creation was approximately $35 trillion dollars. Five companies accounted for 10% of it, while the top 90 performing companies (0.36% of the total) collectively accounted for more than half, and only 1,092 companies, slightly more than 4% of the total, accounted for all of the wealth-creation.

Assuming that this pattern continues into the future, what does it mean in relation to our investment choices today?

The total number of publicly listed companies on U.S. exchanges has varied over time. It peaked at around 8,000 in the mid-to-late 1990s, and currently stands at around 6,000 across the NYSE and Nasdaq combined. If only 4% will drive long-term wealth-creation, then only 240 of these companies are worthy of being considered as long-term investments.

How 4% Of Stocks Make All The Difference

Bessembinder explains his findings in terms of the asymmetry of the stock return distribution curve.

To break it down, on a flip of a coin, we expect to see a normal distribution of outcomes: half of the flips will yield ‘heads’, while the other half will be ‘tails’. This implies reversion to the mean over the long term where the ‘mean’ (arithmetic average) equals the ‘mode’ (the most frequent outcome).

However, when investing in stocks, the distribution of probable outcomes has an asymmetric skew to the right, with the curve assuming the appearance of having a very long tail3. This is because when investing in a company the loss is capped at 100% of capital, but the potential gains far exceed 100% and tend towards infinity.

To provide an idea of how long the tail can be, Bessembinder’s study identifies Altria Group, one of the world's largest producers and marketers of tobacco, cigarettes and related products. From 1926 until the end of the study period achieved, it achieved a lifetime buy-and-hold return of 244.3 million %, compounding invested capital at a remarkable 17.65% CAGR over 90 years.

So, for the stock market as a whole, while the ‘mode’ (the most frequent outcome) is pulled to the left as most stocks underperform, the ‘mean’ (arithmetic average) is pulled to the right because a small number of winners generate huge outsized returns. This skews the arithmetic average, thereby resulting in the market as a whole over performing.

Since the market is ‘mean’ reverting, this skew is favourable for stock market investors.

The Venture Capital (VC) business operates on a very similar basis. A VC fund may invest in 100 start-ups in the knowledge that most will fail or else underperform, but it only takes two or three winners to offset losses on the remainder and generate a positive overall outcome.

What Are The Implications Of These Findings?

These findings have several important implications for investment strategies and performance evaluation.

First, they seem to reinforce the value of portfolio diversification. Non-diversified portfolios risk missing out on the few stocks that generate the exceptional returns that result in alpha being achieved over returns on risk-free assets.

This study largely explains the success of passive funds in recent years.

Similarly, the positive skewness in returns helps explain why active fund managers, who are by definition less diversified, frequently underperform. Unless their selective portfolio include a significant weighting of the 4% of companies that generate all of the alpha, they are doomed to underperform. Statistically, the odds are very much against them and so only a small number of very skillful active managers achieve consistent long term outperformance.

However, for the small number of exceptional active managers, these findings justify concentrated portfolios. If an investor is confident in his ability to spot the outperformers, then a concentrated buy-and-hold portfolio of these businesses will generate extreme positive returns. This explains the methods of ultra successful investors including Warren Buffett, Philip Fisher and Li Lu - all of whom are strong advocates of holding onto high-quality stocks for many years, even decades.

This makes perfect sense when one understands that in a universe of thousands of public companies, there are very few great investments - if you find one, hold on to it for as long as you can. Buffett has owned American Express since 1965 and Coca-Cola Since 1989 - he still holds them both today.

If you consider some of the wisdom Buffett has shared over the years, in this context it makes so much sense:

“An investor should act as though he had a lifetime decision card with just twenty punches on it.”

“Successful investing requires discipline, patience, and a long-term perspective. If you aren’t thinking about owning a stock for 10 years, don’t even think about owning it for 10 minutes.”

“Diversification is protection against ignorance. It makes little sense if you know what you are doing.”

“Opportunities come infrequently. When it rains gold, put out the bucket, not the thimble.”

“Investing $1,000 in Apple is a decision not to invest that $1,000 in Microsoft. Investing is not just about finding good companies, it is about finding the best place to put your money.”

“If somebody shows us a business, the first thing that goes through our head is would we rather own this business than more Coca-Cola? Would we rather own it than more Gillette? It’s crazy not to compare it to things that you’re very certain of. There are very few businesses that we’ll find where we’re as certain about the future as we are at companies such as those.”

“All there is to investing is picking good stocks at good times and staying with them as long as they remain good companies. Calling someone who trades actively in the market an investor is like calling someone who repeatedly engages in one-night stands a romantic. The stock market transfers money from the active to the patient. Our favorite holding period is forever. Time is the friend of the wonderful company, the enemy of the mediocre.”

It should be noted that the Bessembinder study focused on 'enduring wealth-creation,' meaning businesses that consistently created value from their initial listing until the study’s last data point. This focus naturally excludes cases of 'transitory wealth-creation,' where a company experienced a period of significant wealth generation on the way up, only to later destroy wealth as its fortunes declined on the way back down. This distinction suggests that a skilled active fund manager who opts for a strategy of regular portfolio rebalancing, similar to Joel Greenblatt’s investment style, rather than a long-term buy-and-hold Buffett approach, could potentially achieve returns that outperform Treasury bills by investing in an entirely different set of companies to the top 4% identified in Bessembinder’s study. However, such an approach is fraught with difficulties. It demands exceptional skill (or luck) in both identifying the next wave of short-term performers and then timing both the entry and exit of each portfolio investment. Additionally, the increase in trade frequency results in significant transaction costs and tax-related value attrition, both of which adversely affect compounded returns. For this reason, Bessembinder concentrates on the rare 'great investments' that are suited to a long-term buy-and-hold strategy.

Does Other Data Support These Findings?

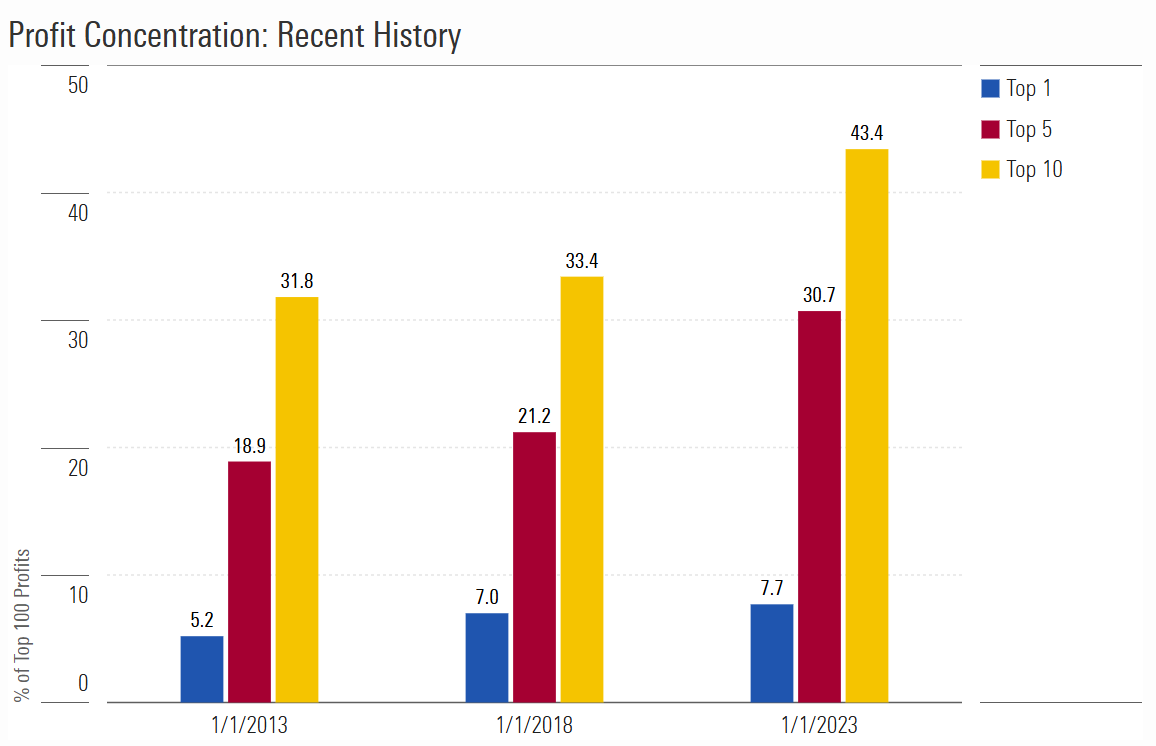

MorningStar, the Chicago-based online investment research firm, conducted analysis based on corporate profitability relative to the market as a whole.

Unsurprisingly, similar levels of concentration were found in this data also. A small number of top-performing companies contribute disproportionately to the aggregate profits of the market.

The study involved taking earnings of:

the single highest-earning firm in a given year (Top 1);

the five highest-earning businesses of the year in question (Top 5);

the ten highest-earning companies in that year (Top 10);

then dividing those totals by the summed earnings of the 100 highest-earning US companies. The results for 2013, 2018, and 2023 appear in the chart below. Over the course of 10 years, the profit share from the five largest companies spiked from 18.9% to 30.7%, while that for the top 10 firms increased from 31.8% to 43.4%. Without question, a small number of companies are still dominating in the market today.

You may be thinking that this is a recent phenomenon due to the dominance of rapidly scalable tech companies, but you would be wrong. The 1950s and 1960s experienced higher stock market profit concentration than is the case today. To demonstrate, the same analysis was conducted back to the 1960s (see chart below, the colours and key correspond to the chart above).

In 1963, the 10 most successful businesses booked 51% of the top 100′s profits. This group consisted of five oil companies, two auto manufacturers, two conglomerates, and IBM as the only technology business. It becomes clear that U.S. industry was even more top-heavy then than it is today.

Since earnings, are used to benchmark valuations, it should come as no surprise that the few companies which generate the lions-share of profits earn far higher valuations than all others. This is explains their heavy weighting in stock indices.

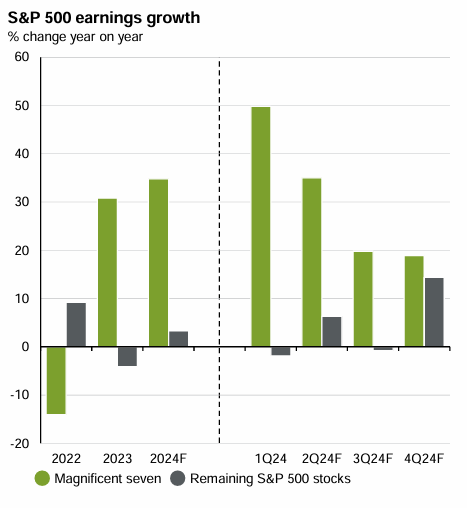

High earnings growth results in a higher earnings multiple as shown in the following chart:

And since these factors are multiplicative in terms of corporate valuation, it is hardly surprising that these companies enjoy accelerated valuation growth.

This pattern can be traced way back in history. In the late 1950s, three stocks accounted for almost 30% of the S&P’s value: AT&T, General Motors and IBM. It's worth noting that this group of dominant companies reflected the industrial and technological landscape of the time, with a focus on telecommunications, automotive manufacturing, and early computing.

These companies, along with Standard Oil, General Electric, du Pont, and U.S. Steel, were consistently among the largest and most influential companies in the United States during the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. They remained among the ten largest companies for most of those three decades, with their positions sometimes changing but their dominance persisting.

Today we have Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Nvidia, Amazon, Tesla and Meta leading the charge and commonly referred to as the Magnificent Seven. The names have changed, but the dynamics of the market are largely unchanged.

The chart below shows how, in 2023, the S&P500 index increased by 19%, and how this breaks down as a contribution of a 71% gain from the Magnificent Seven, with the remaining 493 stocks returning an average of only 6%, giving an average gain of 19%. Seven out of 500 companies made all the difference.

To add balance to this analysis, it should be noted that 2023 followed a large draw-down in 2022 during which the Magnificent 7 were down 39%, while the remainder of the market only fell 11%. So this phenomenon can work both ways. However, on balance, over the long-term, it has always been a small number of big companies driving positive stock market returns.

Just to prove that this really is nothing new, the chart below, dating back to the 18th century, shows the market cap of the largest, five largest and ten largest companies by market cap as a percentage of all listed companies. When the number of public companies is small, these numbers are less reliable, but as the stock market achieved critical mass, around the mid 1800s, the pattern stabilized and has been relatively consistent ever since.

It becomes clear that as companies grow, they leverage their scale and resources to dominate, resulting in a "winner-take-all", or “winner-takes-most”, market situation. This explains why the valuations of a few companies rapidly accelerate, leaving the rest of the market in their wake.

Valuations are so extreme that the combined market value of the Russell 2000 Index, which includes about 2,000 of the smallest U.S. companies, is currently less than that of Microsoft alone.

Some of this can be justified on the basis that over 50% of companies in the Russell 2000 small-cap index are reportedly unprofitable and far riskier, attracting a lower earnings multiple which would suggest that even if their aggregate profits were equal to those of Microsoft, they would still be valued at less than Microsoft.

At this point you could be forgiven for thinking to yourself that you ought to construct your portfolio entirely of the largest most dominant companies and simply adopting a buy-and-hold strategy. But that overlooks a crucial aspect of investing: even the best companies at the wrong price make for a poor investments.

Unsurprisingly, the strongest companies are the most popular amongst investors and that frequently translates into inflated stock market valuations, creating a significant risk for investors. After a period of remarkable growth and market dominance, even the Magnificent Seven have experienced significant drawdowns from time to time.

Consider Meta (formerly Facebook) which experienced a dramatic decline in 2022, with its stock price plummeting to a low of $88.91 in November of that year, representing a decline of nearly 75% from its peak in 2021. In that same year, Tesla fell about 65%, while Amazon and NVIDIA dropped 50%. These significant losses stemmed from a combination of factors: company-specific issues like Meta's spiraling costs, post-pandemic stock market euphoria subsiding; and broader macroeconomic pressures such as rising interest rates and inflation concerns.

The potential for disastrous outcomes when investing in successful companies at inopportune times highlights the complexity of portfolio construction. It's not enough to simply select top-performing businesses; investors must carefully consider the price of securities relative to their intrinsic value. This necessitates a deep understanding of the factors that can cause valuations to diverge from economic reality.

Valuation Dislocations

So far we've observed that a small number of companies contribute disproportionately to total market earnings, leading to their outsized growth in market capitalization (valuation). This trend aligns well with economic logic and appears rational. However, other less economically rational factors also influence corporate valuations and these can lead to pricing dislocations, so they need to be fully appreciated and understood.

Most major global indices, like the S&P 500, use a free-float capitalization-weighted approach, where a company’s weight in the index grows as its market capitalization increases. While this methodology has been effective for many decades, the past 10–15 years have seen a shift in market dynamics. Passive investing now dominates, and share buybacks, often used to offset dilution that would otherwise occur from stock-based compensation, have become commonplace. These factors combine with this methodology to create a feedback loop that significantly distorts valuations.

Here’s how this works: take a strong company like Apple. High demand for its stock drives up its share price and its market capitalization, leading to a larger index weight. Passive funds, which are mandated to match the index weighting, apply a greater share of new money flowing into their fund to that company, regardless of the share price because they are blind to the economic fundamentals of the business. Contrary to the generally accepted dynamics of supply and demand, in this scenario demand increases as price goes up - so much for the efficient market hypothesis! In combination, these factors create share price momentum to the upside, attracting speculative buyers driven by fear of missing out (FOMO), which accelerates the upward momentum still further.

Simultaneously, the company issues a significant amount of stock-based compensation in what can only be described as an iniquitous transfer of wealth from shareholders to insiders. Then management repurchase shares, typically without any regard to price or intrinsic value. Not only does this destroy shareholder equity, but it creates artificial demand for the shares that is entirely detached from the economic fundamentals of the business. The repurchases are designed to both offset dilution, masking the iniquity of the situation, and to artificially inflate the share price so that the share grants are worth more to the insiders receiving them. It’s tantamount to market manipulation in which the regulator is complicit through acquiescence. Trillions of dollars are being pumped into the U.S. stock market this way, inflating share prices well beyond their true intrinsic value. This ‘fake demand’ for the the stock of the business, enhances its market cap which causes its index weighting to grow. Then passive funds are compelled to increase their holdings once again, perpetuating the cycle. This feedback loop continues until valuations become stretched to extreme levels.

From 2022 to 2024, Apple's market cap rose from $2.0 trillion to $3.4 trillion, despite declines in top-line revenue, net income, and free cash flow over the same period. How could this happen? In answer to that question, consider that across financial years 2022, 2023 and 2024 Apple spent a total $279 billion on stock buybacks, reducing its share count by 872 million shares. Effectively, this implies that Apple paid $320 per share removed from the total share count. Given that the average share price during this period was around $180, approximately $122 billion of corporate capital flowed into the bank accounts of insiders.

Shareholders tend not to notice such things when the share price is rising, albeit artificially, because on the face of it everyone appears to be winning. However, this is a misallocation of capital and a destruction of shareholder equity on an epic scale. It is tantamount to a breach of fiduciary duty at the very least, arguably criminal at worst. Regulators, it’s time to wake up!

In such circumstances, it’s no surprise that Buffett, who has always valued the honesty and integrity of management in the companies in which he is invested, is selling down his Apple shareholding.

Apple isn’t alone in this practice - such behavior is widespread across U.S. public markets, especially in the tech sector.

The interesting part of this narrative is that such valuation distortions would almost not have occurred had the market been made up entirely of active investors. So this raises a legitimate question: has passive investing destroyed the efficiency of markets?

The late Jack Bogle, founder of Vanguard and the godfather of passive investing, stated “If everybody indexed, the only word you could use is chaos, catastrophe.” That was in 2017 at the Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting. He went on to say, “So [the market] gets a little less efficient, but … it’s going to take a long, long time [for indexing to get] anywhere near 50% [of the market].”

As discussed above, I fear that he was correct in his first assertion that passive trading has the potential to cause chaos, but he was wrong about the time scales over which it would become the dominant form of investing.

In recent years passive investing has significantly overtaken active investing in the US stock market, with passively managed funds now controlling more assets than their actively managed counterparts for the first time. Passive investing's market share has risen from about 1% in the early 1990s to well over 50% today. The trend is further illustrated by the substantial net inflows into passive US equity funds ($244 billion) in 2023, contrasted with the significant net outflows from active funds ($257 billion) during the same period. This transformation reflects investors' growing preference for low-cost, index-tracking strategies that aim to match market returns rather than attempting to outperform them.

So, were Bogle's comments truly prophetic? Has chaos finally arrived?

The primary mission of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is to maintain fair, orderly, and efficient markets while offering protection to market participants. So why has it failed to address this growing issue?

Historically, the SEC has been more reactive than proactive. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 came in response to major accounting scandals involving companies like Enron and WorldCom. Similarly, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 was enacted in response to the 2008 financial crisis.

It appears that only another financial crisis might spur the regulator into action. As investors, this means we cannot rely on the SEC for protection; instead, we must understand the risks ourselves and take strategic steps to safeguard our investments and our capital.

Is The Market Running Too Hot?

For most of history, the value of companies in the economy grew in parallel to the economy itself. This seems like a logical outcome given that the economy is worth the output of the companies operating within it, so the two should be inextricably linked.

The chart below demonstrates how stock market indices, both the S&P500 and the Wilshire 5000 (a broad-based market capitalization-weighted index that seeks to capture 100% of the United States investible market), have until recently tracked GDP closely. However, since the end of the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2009, that relationship has broken down, and in recent years there seems to have been a complete dislocation.

Both the S&P500 and Wilshire 5000 are up approximately 5,000% from 1972 to 2024, while GDP has only increased by close to 2,000% and most of the outperformance of the equity markets has occurred since 2009.

So what’s going on?

The chart below shows net demand for US equities since 2000. It demonstrates that the net outflows of capital from Pension and Mutual funds in combination with the inflows of capital from Households (retail investors) and Foreign investors, results in a net deficit of $0.3 trillion ($2.4 trillion - $2.7 trillion). Corporations buying back their own shares, largely to offset dilution, thus account for all of the net demand for equities over the past couple of decades and then some. Most of this activity has occurred since 2009 when real interest rates were taken below zero and money supply was expanded through quantitative easing - so the Federal Reserve is partly to blame.

So how can we assess whether or not these distortions to the efficient functioning of the market have resulted in the market running too hot?

The relationship between GDP and the value of the stock market has gained prominence as a valuation indicator for the stock market as a whole. In a Fortune Magazine interview back in 2001, Warren Buffett referred to it as "probably the best single measure of where valuations stand at any given moment." Buffett appreciates this indicator for its alignment with his fundamental approach to investing, focusing on underlying economic value rather than market sentiment. He believes in the principle of mean reversion, where market valuations tend to return to historical averages over time, and this indicator helps identify potential overvaluation or undervaluation relative to the mean. Additionally, it serves as a contrarian tool, signaling when the market might be overly optimistic or pessimistic, which can aid in making contrarian investment decisions.

The ratio that Buffett uses is calculated by dividing the total market value of all US publicly-traded stocks (Wilshire 5000) by U.S. GDP. The chart below is a graphical representation of that ratio over time with recent peaks labelled for reference. We can see how mean reverting the market has been until 2009.

The long term mean is around 85%, shown by the dotted line, and this has held true for much of the 20th Century. The peaks shown coincide with the dot-com bubble in 2000 which pushed the ratio to over 130%, and a smaller peak in 2007 just before the GFC which pushed the ratio to around 115%. Both of these peaks were followed by reversion to the mean.

However, from 2009 until today we have experienced the longest bull run in stock market history which has taken this ratio to well over 200% for the first time ever (currently closer to 209%). Not only is this entirely unprecedented, but it far exceeds prior peaks. This level is about 2.2 standard deviations above the historical trend line, indicating strong overvaluation.

While this doesn’t necessarily signal an imminent correction, Buffett argues that the ratio indicates, at a minimum, that investors should anticipate relatively low returns from the stock market in the coming years, as much of the economy’s future growth is already priced into equities. In other words, either the economy needs to catch up with current corporate valuations, or else valuations must adjust downward to align with reality.

Particularly relevant to this article is the fact that many companies responsible for distorting the stock market through largely unjustifiable stock buybacks since 2009 are those belonging to the 4% which Bessembinder identifies as typically being responsible for generating long-term alpha. Does this suggest that now may be a particularly risky time to allocate capital to these companies?

We find ourselves in uncharted waters. Has the feedback loop described above, exacerbated by lax monetary policy since the GFC, created the biggest stock market bubble of all time?

The efficient market hypothesis states that share prices reflect all available information, so stocks trade at their fair market value at any given time. But this assumes that investment decisions are being made based on available information. When the market chooses to ignore all available information and blindly purchase stock at any prices to fulfill a passive fund mandate or to offset dilution from regular grants of stock based compensation, the efficient market hypothesis completely falls apart. Divergence from fair value will increase over time, which is exactly what we have witnessed since 2009.

It’s important to consider a few caveats. The exceptionally low interest rate environment from 2009 to 2022 likely justified somewhat higher valuations by boosting earnings, while the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), which lowered U.S. corporate tax rates from 35% to 21%, also provided a lift to net earnings and valuations. However, neither of these factors fully accounts for the scale of today’s valuation dislocation or explains why this concerning trend persists. Notably, the zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) era has ended, and the TCJA’s boost to valuations was a one-time effect that could be reversed if taxes rise to address the U.S. national debt. Altogether, these elements contribute to the fragility of the current situation.

Conclusion

The research conducted by Professor Bessembinder sheds an entirely new light on the dynamics of the stock market. His findings challenge conventional wisdom and force us to rethink our assumptions about investment returns.

The extreme concentration of returns in a small number of companies has profound implications for investment strategies. It becomes clear that the true skill lies in identifying those rare outperforming companies and concentrating bets on those businesses - a strategy employed by legendary investors like Warren Buffett. However, the odds are heavily stacked against the average active manager.

For most investors, as Buffett has always advised, passive investing may indeed be the best option, but it is not without its own challenges. The rise of passive investing, coupled with distortive factors like gratuitous stock buybacks, appear to be creating feedback loops that are distorting the market and driving valuations further and further from underlying economic fundamentals. This dislocation poses risks that investors and regulators must grapple with.

For the past 15 years, we have seen the longest bull run in stock market history, marked by periodic bumps, including the COVID-19 pandemic, none of which managed to derail its momentum.

Money was so easy to make during this period, often referred to as the "everything bubble," that nearly everyone fancied themselves a financial expert with the Midas touch. In truth, even a monkey could have made money during this time.

Money flowed blindly into passive funds, stock buybacks hit unconscionable levels, regulators were largely inattentive, and investors relished watching their capital grow. Yet, few stopped to question the sustainability of it all, and even fewer had the expertise to truly understand what was happening.

As we stand at what may be the end of an unprecedented era of easy money and perpetual growth, investors face a stark new reality. The tides that buoyed nearly every asset are now receding, and those without the wisdom or preparation for a changing market may be caught off guard. This transition requires a recalibration of expectations, moving away from a time of easy gains, to a climate demanding strategic insight and caution. True expertise will distinguish those who can navigate a more challenging landscape from the rest.

Bessembinder, Hendrik (Hank), Do Stocks Outperform Treasury Bills? (May 28, 2018). Journal of Financial Economics (JFE), Forthcoming, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2900447 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2900447 and the updated study which compiles compound return outcomes for 98 years, through the end of 2023 SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4897069

The Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) is a vendor of historical time series data on securities. It is affiliated to the University of Chicago's Booth School of Business, a nonprofit organization that tracks information on more than 32,000 active and inactive securities listed on all the major U.S. exchanges. It is used by academic, commercial, and government agencies to access information on securities such as the rates of returns on stocks.

The strong positive skewness in long-term returns suggests that standard performance measures like the Sharpe ratio, which assume normally distributed returns, may be inadequate for evaluating long-term investment performance.

Warren Buffett has amassed a record $325 billion in balance sheet cash at Berkshire Hathaway according to its most recent quarterly results. He has sold off significant portions of his Apple and Bank of America holdings, reducing his equity market exposure.

He has paused his repurchases of Berkshire stock - he only buys back stock when he considers it to be trading below intrinsic value.

He also recently described what he is seeing in the market as "casino-like behaviour".

What does this say to you about his assessment of current market valuations and economic conditions?