Part 1: The Capital Cycle To Boost Returns

How Marathon Asset Management Sees What Others Miss

This is the first in a two-part series.

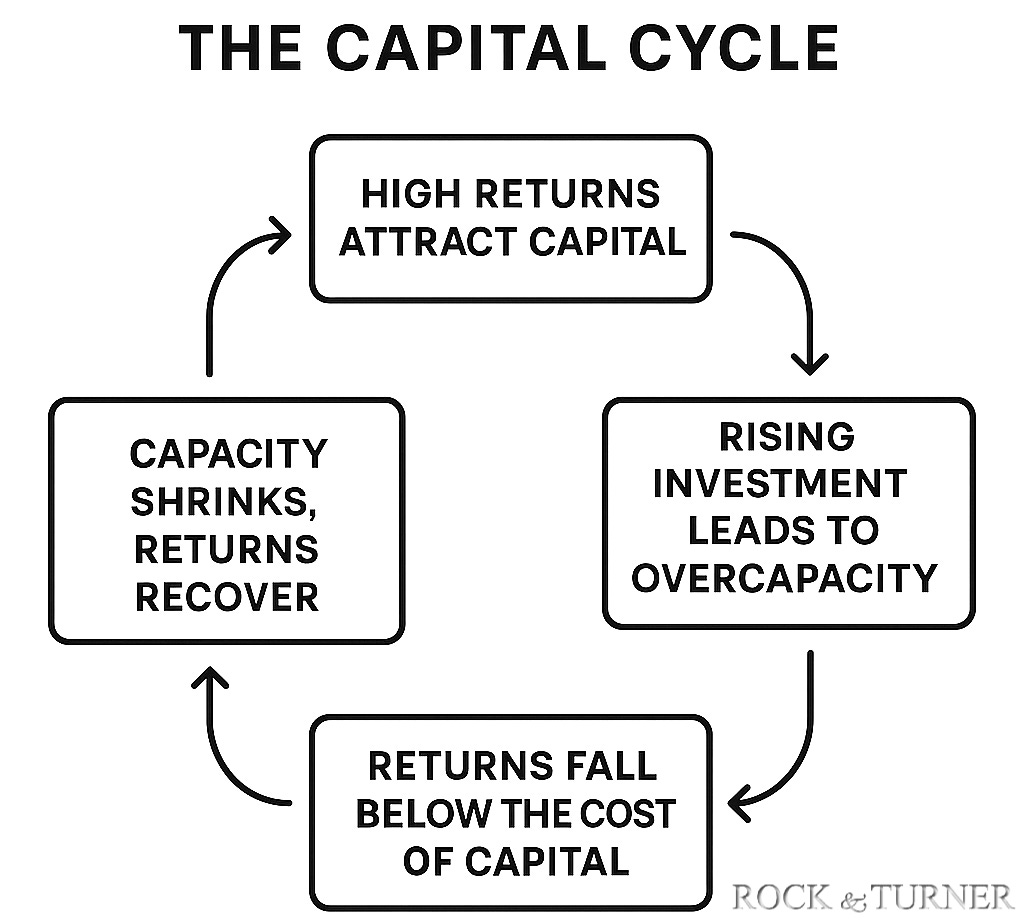

The Capital Cycle is something that significantly boosts returns of those that understand it, yet so few do. So, first I’ll explain how it works.

Then, in the second part, I’ll explore a Capital Cycle opportunity that is starting to unfold - the timing may be perfect.

Gain an Edge when Investing

Most investors obsess over demand. What’s trending? What do consumers want? What’s growing fast?

Marathon Asset Management thinks differently. Instead of chasing what's popular, they focus on where the money is flowing. Their secret weapon is something they refer to as Capital Cycle Theory - a powerful, supply-side framework that doesn’t just explain industry booms and busts, it helps predict them. Made famous by Edward Chancellor’s book Capital Returns, it’s a roadmap for finding opportunities when others see only trouble.

When an industry becomes highly profitable, it naturally attracts a rush of investment. Companies start pouring money into growth, new players jump in, and everyone scrambles to grab a slice of the market. It’s a feeding frenzy. They all aim at expanding capacity. But this is where the trouble begins.

Imagine living in a community where food is scarce. Naturally, you’d think it’s smart to turn any land you own into farmland. So you take your life’s savings - and even borrow some money - to buy a plough and plant seeds, expecting a big harvest next year.

At first, everything seems to be going according to plan.

But there’s one thing you didn’t count on: everyone else had the same idea.

When harvest season arrives, the fields are overflowing with crops. There's so much food that some of it ends up rotting away. Prices crash. Suddenly, the money you expected to earn isn’t there. Debt repayments start to feel heavy.

You think about selling your plough and equipment to free up some cash - but who’s buying? No one wants to expand their farms now that farming looks like a losing bet.

Low prices in the market cause weaker players to exit and investment is withdrawn, so supply tightens once again. As profitability creeps back, the economic winter ends and green shoots of recovery emerge.

“The cure for low prices, is low prices”

Survivors - often the disciplined investors who bought distressed assets on the cheap, enjoy a healthier market during the recovery. It’s Darwinian survival of the fittest at play in an economic sense - not only do these businesses survive, but they thrive.

This is the point at which the whole cycle starts again.

Economic cycles have been part of human history since the dawn of time - we’ve always known they exist - they’re woven into the very fabric of our culture. It’s a story that feels almost timeless - one that echoes the biblical tale from the book of Genesis, where Egypt enjoyed seven years of abundance, only to be followed by seven years of famine.

Yet, despite all that history and the predictability of these cycles, very few people know how to navigate them and fewer still use them to their advantage.

This isn’t just theory - it plays out in the real world all the time and if these cycles are played properly, an investor is easily able to use them to boost returns - which is exactly what Marathon Asset Management always did.

So first, let’s dive in to a few real-world examples:

(1) Shipping

The global dry bulk shipping market went through a massive boom in the mid-2000s. China’s infrastructure buildout sparked huge demand for iron ore and coal, and freight rates soared.

If there appears to be money to be made in shipping, everyone has the same bright idea at the same time - they all spot a gap in the market - building a ship seems to be the sensible thing to do. But because building new ships takes years, it’s only later - often all at once - that all this new capacity arrives at the same time, flooding the market. Suddenly, the world was swimming in excess shipping capacity - there was way more supply than anyone actually needed.

Shipping rates collapsed and the value of the ships plunged. From 2009 to the mid-2010s, the sector was decimated. Margins shrink, returns dip below the cost of capital, and the easy money dries up. Investors retreat. Some companies fold. But as older ships were scrapped and new orders dried up, supply gradually tightened. By the time demand rebounded post-COVID, there weren’t enough ships. Shipping rates spiked again.

(2) Commercial Real Estate

Unlike tech or consumer goods, where supply can shift relatively quickly, commercial property - whether office towers, shopping centers or logistics warehouses - take years to bring online. From the moment a company decides to build, it’s a long, complicated journey - site selection, design, permitting, demolition if needed, and finally construction. The whole process typically drags out over three to five years.

In the early 2010s, after the Great Financial Crisis (GFC), new construction of offices had stalled. Developers were cautious, financing was tight, and no one wanted to build. But by 2015–2019, with interest rates low and demand recovering, capital surged back in. Construction boomed - especially in major cities like New York, San Francisco, and Chicago. Then came the pandemic. Remote working exploded. Office demand cratered. But the buildings were still under construction. They had to be finished, leased, and maintained - regardless of market conditions. Suddenly, cities were flooded with excess supply just as demand dried up. The result? Vacancy rates rise. Rental yields fall. Returns plummet. A glut of empty offices, collapsing valuations, distressed asset sales and a slow, painful correction. Because supply can't just be “turned off,” recovery takes years, not quarters.

(3) Energy

After years of underinvestment following the 2014 oil crash, the sector entered the COVID-19 era with barely any slack in production. When global demand came roaring back in 2021–22, energy prices soared - not because demand was unusually strong, but because supply had been neglected for so long. It takes years to develop oil fields or build new refining capacity, so you can't just "add supply" overnight. Investors who understood the capital cycle and saw that no one was investing, were positioned perfectly when prices surged.

Investors: Gaining Advantage From Capital Cycle Theory

Great management teams aren’t just good operators. They understand the capital cycle. Not only do they resist the urge to expand during booms, but they choose to invest during busts.

Marathon Asset Management looks closely at this when choosing where to invest.

Let’s explore some great examples from an investors view point.

Nucor (NUE) is a standout example. In the highly cyclical steel industry, Nucor's leadership (especially Ken Iverson) showed extraordinary discipline. Rather than rushing to build capacity during boom times, Nucor stayed cautious. They focused on maintaining a flexible, low-cost production model and expanding opportunistically by acquiring distressed assets or expanding when competitors were retreating, taking advantage of favourable market conditions and maintaining a strong balance sheet. Under Iverson, despite operating in a cyclical industry with periodic volatility, Nucor didn’t report a losing quarter for over 25 years.

Sam Zell is another great example. Known as the "Grave Dancer", he made a fortune by understanding when industries were overbuilt. In the run-up to the 2008 real estate crash, most people were aggressively buying overvalued assets, yet Zell sold $39 billion worth of his portfolio at peak valuations, including the sale of major assets like his Equity Office Properties to Blackstone Asset Management. After the bust, when capital had dried up and prices collapsed, he made a fortune by buying distressed real estate assets for pennies on the dollar when others were fleeing.

RyanAir (RYAAY) CEO, Michael O’Leary, played the capital cycle perfectly during the COVID-19 pandemic. While other airlines sought to reduce their fleets, collapsed into bankruptcy or exited markets, O’Leary used Ryanair’s strong balance sheet to negotiate steep discounts on a large number of Boeing 737 MAX aircraft while the market was weak. Acquiring new, fuel-efficient aircraft at a lower cost than would have been possible pre-pandemic widened RyanAir’s cost advantage over competitors. After the pandemic, when the travel industry rebounded, Ryan Air was poised to succeed and increased both its market share and profitability as a result.

The Big Takeaway

Understanding Capital Cycle theory gives an investor a serious edge. By looking where others aren’t - at supply dynamics, management behaviour, and sectors everyone has abandoned - you can spot opportunities that others miss.

If you spot a CEO exploiting the capital cycle in the way that Michael O’Leary, Sam Zell and Ken Iverson did - that becomes a clear signal to invest in the business that these people are managing - those will be the long-term winners.

Similarly, if you can see a capital cycle playing out in an industrial sector, that too is a strong signal for investors.

In a market driven by hype and herd behaviour, this kind of clarity is priceless.

Are there any capital cycle plays available now? Yes there are.

In the next part in this series, I’ll look at a real time Capital Cycle opportunity worthy of exploring:

Great write up. Concise & to the point. Thanks for sharing.