Part 2: Capital Cycle Opportunity in PGMs

The Challenge Is Always Timing - For PGM Producers The Time May Be Now

DISCLAIMER & DISCLOSURE: The author holds a position in Sylvania Platinum at the date of publication but that may change. The views expressed are those of the author and may change without notice. The author has no duty or obligation to update this information. Some content is sourced from third parties believed to be reliable, but accuracy is not guaranteed. Forward-looking statements involve assumptions, risks, and uncertainties, meaning actual outcomes may differ from those envisaged in this analysis. Past performance is not indicative of future results. All investments carry risk, including financial loss. This analysis is for educational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or recommendations of any kind. Conduct your own research and seek professional advice before investing.

A Capital Cycle Situation Unfolding

In Part 1 of this series, we unpacked the fundamentals of Capital Cycle theory. Now, in Part 2, we turn our attention to a real-world example that might just be unfolding before our eyes.

Allow me to introduce you to a small group of metals that have been quietly overlooked: the platinum group metals, or PGMs. These include platinum, palladium, rhodium, iridium, and ruthenium.

These metals have endured years of low prices, tight capital, and narratives of irrelevance in an electrified future. But dig a little deeper, and a different story emerges - one not of decay, but of deep value, structural deficits, and potential outsized returns for those who understand the rhythm of the capital cycle.

A Market in Transition

Let’s rewind a bit. The PGM market was once awash in supply. Production peaked in 2007, right as prices hit new highs. But what followed was a slow-motion unraveling. Oversupply and inventory build-up weighed down the market. Then the 2008 financial crisis struck. Given how closely platinum’s fortunes are tied to industrial demand, the impact was brutal — prices collapsed.

With prices in the doldrums, capital dried up leading to chronic underinvestment in new mines and expansion projects throughout the 2010s which has reshaped the supply landscape. Exploration and development slowed. The supply base eroded.

Then came a string of new shocks: the COVID-19 pandemic, geopolitical instability (Russia-Ukraine) and now, mine closures like Sibanye Stillwater’s ‘Stillwater West’. Each event further tightened the screws on production and tightened supply.

The result? A market that now faces persistent and significant structural deficits.

Doesn’t this sound like a classic capital-cycle set-up?

The capital cycle framework is simple but powerful. When prices are high, capital floods in. When prices fall, capital flees. The exit of capital eventually curtails supply, tightening the market and sowing the seeds for the next upcycle.

Between 2014 and 2024, industry capex averaged about $240 per ounce, which is approximately $175 lower than the previous decade. This annual underspend equates to a cumulative shortfall of around $18 billion across the sector over the decade. For context, the combined market capitalization of listed South African PGM companies was about $21 billion, so the $18 billion capex underspend is monumental and will be difficult to overcome in the short- to medium-term.

Years of low prices and investor apathy have choked off supply, just as the fundamentals start to turn and these metals remain essential to key industrial and environmental technologies.

PGMs are a textbook example of this cycle in motion.

The Background To This Situation

According to the World Platinum Investment Council, the platinum market is walking a tightrope. Both primary production and secondary sources (recycling) are insufficient to meet current demand, creating a projected shortfall of one million ounces in 2024 alone.

And platinum isn’t the only PGM under pressure. Palladium is in similarly dire straits, facing an even larger deficit - around 1.5 million ounces - worsened by recent production shutdowns. The deficit has reached as high as 15% of total supply - a structural imbalance that’s been years in the making.

Yet against this backdrop, and despite platinum's supply deficit, its price has not kept pace with gold.

Historically, platinum has traded at a premium to gold due to its rarity and strong industrial demand. As the chart below demonstrates, platinum traded for more than twice the price of gold during a brief period in early 2008. However, this ratio has flipped on its head. Today platinum trades at roughly $1,000 an ounce, well below peak prices, while gold has rallied to an all time high of over $3,000.

While one ounce of platinum used to purchase at least two ounces of gold, now a single ounce of gold purchases three ounces of platinum! It’s a crazy world we live in!

But here’s the twist: platinum is far rarer than gold - about 30 times rarer. This price gap defies logic, and if history and scarcity are any guide, it won’t last forever. For patient contrarian investors, this kind of disconnect might just be a golden opportunity - pun fully intended.

So why hasn’t the price responded more dramatically? Classic economics tells us that when demand outstrips supply, prices should rise until equilibrium is restored. But the platinum market doesn’t play by textbook rules. That’s because the supply-demand equation misses a key variable: above-ground inventories (AGI).

In recent years, these stockpiles - built up during periods of oversupply - have acted as a buffer, plugging the gap between falling production and steady demand. China, in particular, has been a major player, importing more platinum than it immediately needs and holding it in reserve.

This means deficits don’t instantly translate to price surges, but the pressure is clearly building. More particularly, these inventories are not infinite. Analysts expect AGI to fall by 31% to just over 2 million ounces in 2025 - equivalent to only three months of global demand.

So why hasn’t speculative investing driven the price higher? For much of the past few years, investor sentiment has remained cautious, weighed down by fears about long-term demand, especially as the world had been shifting towards electric vehicles. After all, around 65% of PGM demand comes from auto-catalysts used in internal combustion engines (ICEs). The logic seems simple: more EVs, less need for PGMs.

But the reality is more nuanced. The EV revolution isn’t rolling out as fast or as smoothly as predicted. In 2024, battery electric vehicle (BEV) adoption outside of China was largely flat, and Europe - a long-time EV cheerleader - saw sales decline. The reason? Cost. BEVs are still significantly more expensive to buy than their ICE counterparts, and the total cost of ownership remains high. For many buyers, hybrids offer a more affordable middle ground - and here’s the kicker: hybrids actually use more PGMs than traditional gas engines.

Yes, you read that right. As consumers pivot toward hybrids instead of full electrics, PGM demand could actually increase. In China, arguably the most EV-enthusiastic market on the planet, the recent growth has been almost entirely plug-in hybrids rather than pure electrics. If this trend spreads globally, the demand curve for PGMs may be far longer and stronger than most expect.

And that’s just the automotive side of the story. There’s also a rising wave of demand from the clean energy sector. PGMs are essential in hydrogen production and fuel cell technology - two areas still in their infancy, but with enormous potential. As the world searches for scalable clean energy solutions and countries continue their drive towards achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, these metals will prove critical.

So while the market has been slow to react, the ingredients for a capital cycle resurgence are all here: constrained supply, a misunderstood demand picture, dwindling inventories, and a huge gap between price and value. For those watching closely, the setup looks increasingly compelling.

The Capital Cycle Opportunity

By the end of 2024, every major platinum group metal finished the year in physical deficit - and the squeeze isn’t easing up anytime soon. Supply erosion is expected to persist, with platinum and palladium production forecast to decline at a compound annual rate of -0.9% and -1.3% respectively through 2029.

This year alone, the World Platinum Investment Council expects mined platinum supply to fall by 6% to 5.4 million ounces. Even when you include recycling, total supply is projected to reach just 7 million ounces - well short of demand. And that’s before considering the recent surge in speculative investor interest.

Investor interest in gold and silver, which has been exceptionally strong in recent years, now appears to be spilling over into platinum. Now consider that this is a tight market where even a modest shift in demand can have an outsized impact. For context, platinum’s annual supply sits at around 7 million ounces - tiny compared to the more than 100 million ounces of gold mined each year. So it doesn't take much to move the needle.

While market dynamics are driving prices higher, the geopolitical backdrop adds another layer of complexity. About 80% of the world’s platinum comes from South Africa, and when you include Zimbabwe and Russia, these three nations account for over 90% of global PGM supply. Each faces its own challenges: South Africa continues to battle crippling energy shortages thanks to ESKOM’s load shedding, Zimbabwe grapples with chronic political and infrastructure issues, and Russia remains isolated from global capital markets due to ongoing sanctions.

While supply remains substantially below demand, and with inventories now dwindling, the only way to bridge the gap is to bring more supply on-line, but with a third of the industry currently operating below breakeven, prices must rise to encourage increases in production.

We are now beyond the tipping point in this commodity market and platinum prices are starting to rise. The movement into the next phase of the Capital Cycle is taking shape. Platinum was trading around $900 as recently as mid-April, but in the month that followed it surged to almost $1,100 - a jump of ~22%.

The price is now hovering near a one-year high and this capital cycle opportunity may just be showing its first green shoots!

Yet, even if prices were to double overnight, bringing on new supply can’t happen instantly - mining is capital intensive and logistically challenging, meaning that new supply is slow to come online.

Major South African producers - names like Impala (Johannesburg: IMP, mkt cap $7.3bn), Sibanye Stillwater (Johannesburg: SSW mkt cap $4.3bn), Anglo American Platinum (Johannesburg: AMS mkt cap $11.2bn), Northam (Johannesburg: NPH mkt cap $3.6bn), and Sylvania Platinum (London: SLP mkt cap $200m) - are trading as if PGM demand is set to vanish and their assets are on the verge of obsolescence. Across the board, their market valuations sit well below asset replacement costs.

This offers a compelling opportunity for brave investors. These are deep value plays in every sense: financially resilient, operationally lean, and geographically entrenched. Yet they’re trading as though collapse in the industry is imminent, despite the fact that the commodities they produce are mission critical and in severe shortage.

It is true that the revenues of PGM miners have collapsed with the fall in the prices of these metals and this, combined with steep mining cost inflation over the past five years, has dramatically reduced margins and made the highest-cost mining areas loss-making - so let’s dig deeper into the numbers.

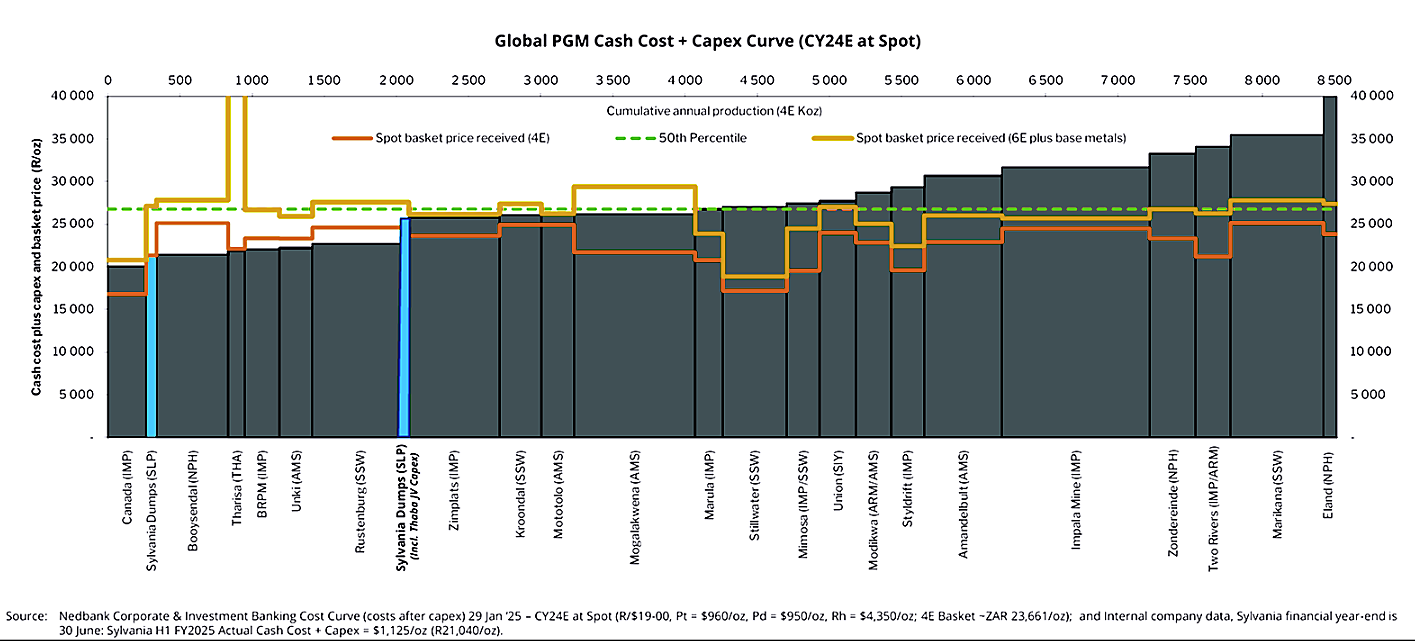

The chart below appears confusing at first glance, so allow me to offer an explanation.

The bars are the All-In-Servicing-Costs (AISC) of each producer - the green dotted line is the average AISC across producers.

The "basket price" refers to the combined value of PGMs (typically platinum, palladium, rhodium, gold, iridium and ruthenium) produced per ounce from a specific mine. Yellow is for a basket of all 6 elements (6E), while amber is for the first four (4E) - although for South African miners, the bulk of the revenues come from the three main PGMs: platinum, palladium and rhodium.

You are probably asking, ‘But why is the basket price different for each producer if spot prices for each element exist in the market?’

Great question!

The answer is that each producer's ore body contains different proportions of these metals, so the realized basket price depends on the mix of metals they extract and sell. For instance, a mine richer in high-value rhodium will realize a higher basket price than one with less rhodium, even if the spot prices for each metal are the same.

It’s now clear that at least half of PGM operations are producing PGMs below operating cost, a situation that simply can’t continue. Companies can’t afford to keep burning cash indefinitely, so cuts are inevitable. That means shutting down some production, and with it comes a hit to future supply. We’re already seeing this happen - between Q1 and Q3 of 2024, more than 14,000 jobs were lost across the sector, and some operations have been mothballed, including Sibanye Stillwater’s ‘Stillwater West’ mine.

This tightening supply sets the stage for rising prices, benefiting the producers that manage to stay afloat. And here’s where the thesis gets interesting: some PGM operations are so well-run that they remain profitable even at today’s depressed PGM prices. These low-cost operators will survive and are poised to thrive as weaker players exit the field. In the long game of the Capital Cycle, they’re the ones best positioned to win.

One standout in this space is Sylvania Platinum, listed in London. Despite a modest market cap of just $204 million, it holds $77 million in net cash and consistently generates around $43 million in free cash flow on a cyclically adjusted basis. It’s among the lowest-cost operators in the sector, run by a sharp and disciplined management team - yet the market treats it like a company on the brink. Its enterprise value is just $120 million, less than half of what it would cost to rebuild its smelting and refining infrastructure from scratch. That’s without even factoring in the value of its proven reserves or its joint ventures.

The light-blue bars on the chart above show how Sylvania’s cost structure compares with and without the capital investment in its Thaba joint venture. The upfront CAPEX for Thaba is roughly ZAR600 million (about US$32 million), plus another US$5 million in working capital, all initially funded by Sylvania. This causes a temporary bump in costs during the development and ramp-up phase, expected to last only 18 to 24 months. Even with that short-term spike, Sylvania still sits firmly in the lower-cost camp. Production from the JV is slated to start ramping up in the second half of 2025, with full output expected in FY26.

Sylvania has no long-term debt, a history of paying generous dividends, and a consistent buyback program. Since 2018, Sylvania - with a market cap of just over $200 million - has returned over $107 million in dividends plus it has repurchased more than 65 million shares - reducing its outstanding share count by around 12.5%, down to 273 million today.

Despite all this, the company trades at a one-year forward EV/EBITDA multiple of just 1.9x, and that’s based on current, deeply depressed PGM prices. If platinum were to return to historical parity with gold, that valuation would look even more compelling.

But there’s more to the story. The South African PGM industry is primed for consolidation. Back in 2016, there were eight listed producers. Today, only five remain. Given the overlapping geography, shared infrastructure, and capital constraints across the sector, it makes sense for that number to shrink further. Sylvania, being the smallest of the remaining five, yet one of the strongest operators, stands out as a logical acquisition target.

As the PGM prices begin to recover, M&A will look increasingly attractive and a merger could unlock real value.

What’s the Play?

For investors, this isn’t about chasing hype. It’s about following the capital - or rather, recognizing where it’s been missing.

The PGM sector has been starved of investment for over a decade. Company valuations are scraping the bottom, reflecting a bleak and possibly outdated view of the future. Yet the fundamentals are beginning to shift.

For contrarian investors willing to dig below the surface, this sector offers something rare: real assets, real scarcity, and real value - just waiting for the market to wake up.

Wow, how do you find this stuff? I think I love you.