Who Was Phil Carret?

Most people, even those in the investment community, will be unfamiliar with the late Philip Carret. However, Warren Buffett considered Carret to be one of his investing heroes, and said of him that he had ‘the best long term investment record of anyone I know.’ So what can we learn from this great man?

Born in 1896, Carret's investing career spanned nearly eight decades, from the 1920s until his death in 1998 at the age of 101. During that incredible career, he founded one of the first mutual funds in the United States, the Pioneer Fund, in 1928, which he managed successfully through the Great Depression and beyond.

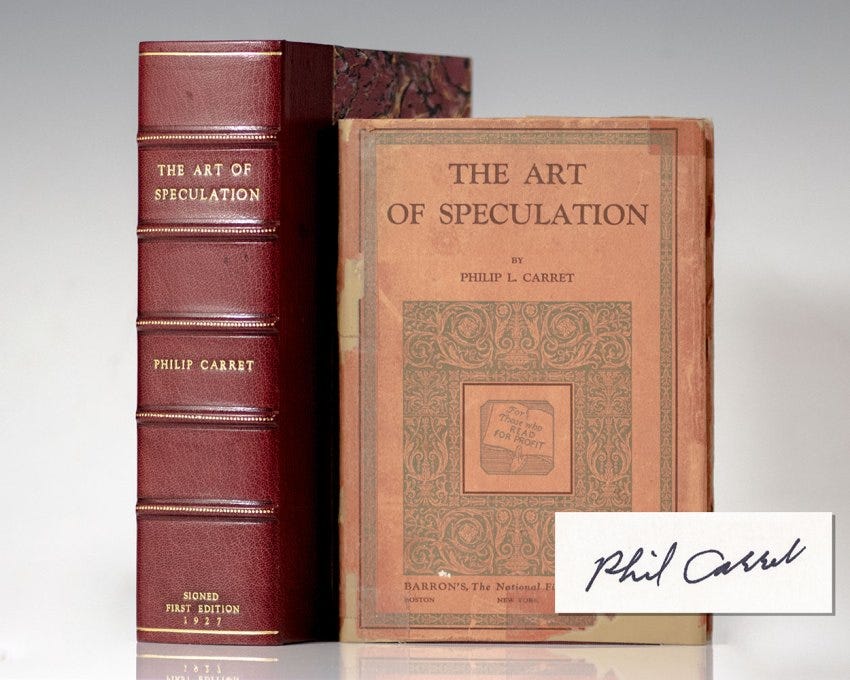

His investment principles are outlined in his 1930 book which was oddly named "The Art of Speculation." The title is peculiar given that Carret adopted a conservative approach, being focused on long-term intelligent investing, which sits at the opposite end of the spectrum to any form of speculation.

Throughout his 55 year investing career managing the Pioneer fund (which subsequently became the Fidelity Mutual Trust), and during a time when companies were tangible asset heavy and so grew slowly, he achieved an impressive average annual return of 14%, significantly outperforming the broader market.

Carret was renowned for his ability to identify undervalued companies with strong fundamentals and for holding onto these investments for extended periods, often decades. He firmly believed that true wealth is built through patience over time, rather than through frequent trading. Sound familiar? Isn’t that exactly what Buffett does?

When taking long-term positions, it becomes crucial to gain a deep understanding of the business and the mindset of its management. Carret, therefore, placed great emphasis on visiting companies, assessing management quality, and focusing on businesses with strong competitive advantages.

“Good management is rare at best, it is difficult to appraise and it is understandably the single most important factor in security analysis.”

Phil Carret

Carret opined that quality management is the single most important factor when investing, yet it receives very little focus from most analysts and investors today. Why? Because it is far easier to take corporate data from a 10-Q or 10-K that is readily available online and enter it into a spreadsheet. It’s just lazy analysis and misses the essence of a good business.

Why Is Management The Single Most Important Factor?

Sam Walton opened his first store in Newport, Arkansas, where his innovative approach to retail - offering exceptional value and always putting the customer first - quickly made it the most successful retailer in the state. However, Walton made a crucial mistake: he failed to include a rent renewal clause in the lease for his store. When the lease expired, his greedy landlord, having seen the success of Walton's business, refused to renew it. Instead, the landlord took possession of the store, handed it over to his son, and Walton lost five years of hard work.

The important takeaway here is that Walton, despite this setback, picked himself up and started over in a new location. This marked the beginning of what would eventually become Walmart. Walton’s new store was just as successful as the first, leading him to open more stores, one after another.

Walton went on to build Walmart into the world's largest and most successful brick-and-mortar retailer, with over 10,500 stores worldwide.

Now, consider that original Newport store. It was hugely successful when Walton managed it, with all the elements of his winning formula and a head start over Walton who had to start from nothing once again. But that original Newport store, under different management, came to absolutely nothing.

Same business, same customers, same location—the only difference was the management, and the outcome couldn’t have been more different.

At the point that ownership changed from Walton to the landlord’s son, analysts could have looked at the financial results of the Newport store from the previous five years. They could have plugged numbers and assumptions into their spreadsheets and discounted cash flow models, but they would have reached entirely the wrong conclusion because no quantitative analysis accounts for the quality of the management.

At that time they would have been best advised to invest in Sam Walton, rather than in the business that he was no longer involved in.

There are countless other examples. McDonald’s, for instance, would not be the global giant it is today without Ray Kroc. Had the business remained solely in the hands of its founders, Dick and Mac McDonald, it would likely still be a single diner in San Bernardino, California. It wasn’t the brilliance of the McDonald’s concept alone that turned it into a worldwide phenomenon and introduced fast food into our lives; it was Ray Kroc’s relentless efforts that made it happen.

Now, consider a commoditized industry like the passenger airline business, where the offerings of each company are so similar that it’s hard to tell them apart. In an industry that has consumed more capital than it has ever created, most airlines fluctuate between profit and loss year after year. Several consecutive years of losses can lead to a cash squeeze and eventual bankruptcy, which is why more airlines have failed over the years than have succeeded. To illustrate, United Airlines has only managed to achieve three consecutive years of profitability before posting a loss. American Airlines and Delta Airlines have fared slightly better, with seven and ten consecutive profitable years, respectively, before encountering a down year. The industry has been so poor for investors, that Buffett once quipped, ‘The way to become a millionaire is to start with a billion in the bank and then buy an airline!’

Against this backdrop, it might surprise you to learn that Southwest Airlines achieved 47 years of uninterrupted profitability from 1973 until 2020, a streak only broken by the COVID-19 pandemic, which grounded all airlines and made it impossible for anyone to profit.

So how did Southwest accomplish this remarkable feat? The answer is Herb Kelleher, its founder and CEO. Once again, it wasn’t just the business itself, but the person behind it, that made all the difference.

Finally, let's consider Apple. Founded by Steve Jobs, who was on a mission to "democratize technology by creating accessible, user-friendly digital tools that could change the world." However, Jobs lacked business management experience. To address this, he wisely brought in John Sculley, a seasoned executive from PepsiCo. The problem was that Sculley’s experience was rooted in a commodity business—a soda called Pepsi—and he was ill-equipped to navigate the rapidly evolving, complex tech world in which Apple operated.

Sculley clashed with Jobs and ultimately fired him, setting off a series of poor management decisions. Nearly 15 years later, Apple was on the brink of bankruptcy, with only 90 days of cash remaining. In a desperate move, Sculley was ousted, Jobs was brought back, and the rest is history. Jobs not only rescued Apple from the jaws of insolvency, but he also transformed it into one of the most successful companies on the planet, now worth over $2 trillion USD.

Once again, it was the same company, with the same products and target market—the only difference was the person in charge, and that made all the difference.

Just to hammer the point home, after being fired from Apple, Jobs founded the software company NeXT, which eventually became the Apple iOS operating system. He was also instrumental in the success of the animation studio Pixar. When Pixar was acquired by Disney, Jobs became its largest individual shareholder, joined the board, and played a pivotal role in its strategy, including the appointment of the legendary Bob Iger as CEO.

In short, whatever Jobs touched turned to gold. If you had been able to invest in everything that Steve Jobs did in his career, you would have done very well.

It’s about finding the right man for the job. While John Sculley was a successful executive, he ought to have remained in his own swim lane. Technology was not his area of expertise.

The same holds true for Lou Gerstner. He had been successful at RJR Nabisco, a biscuit company, but his tenure at IBM was disastrous. His tenure was more about financial engineering than computer engineering. He allowed debt to balloon, impaired the balance sheet, and stripped the business of its core assets. His primary concern seemed to be inflating the share price in the short term to secure bonuses, rather than doing what was best for the company and its shareholders over the long term. A business that Thomas Watson and his son had painstakingly built over 70 years to become the most valuable company in the world was systematically dismantled by Gerstner in just eight years.

Same company, different management, completely different outcome. Once again, it’s not the company but the person at the helm that makes all the difference.

Bill Gates illustrated this point well at the Allen & Company Sun Valley Conference in the summer of 1997. During a panel with Warren Buffett and Roberto Goizueta, then CEO of Coca-Cola, what was expected to be a congenial discussion took an unexpected turn. Gates contrasted the complexity of running Microsoft—a high-tech software company requiring constant innovation and a highly talented workforce—with running Coca-Cola, a commoditized soda business where the product never changes and practically sells itself. He remarked that managing Coca-Cola was so straightforward that "a ham sandwich could do it." Goizueta, very much offended, never spoke to Gates again after that day, but the point was well made.

It would have been entirely inappropriate for someone like Goizueta to have been appointed to take over from Gates at Microsoft. In such a counter factual situation, it would have likely ended as poorly as Gerstner's tenure at IBM and Sculley's at Apple. These leaders simply lacked the requisite talent. Moreover, their egos often get in the way, and when they prioritize their own interests over those of the business, their integrity is certainly called into question.

‘The single most important decision in evaluating a business is the management. I look for people with talent, with character, and with a high degree of integrity. If you have those three things, you can have a tremendous business.’

Warren Buffett

The smartest investors understand this, but most aren't truly intelligent investors. Even major investment funds often prioritize building teams of 'quants' (quantitative analysts) to create increasingly complex mathematical models, rather than hiring people to do the hard work of qualitative analysis.

Berkshire Hathaway doesn't fall into this trap. At a 1996 shareholders' meeting, Charlie Munger joked about the overreliance on DCF (discounted cash flow) models by modern investors, referring to their approach as a "fingers and toes" style of valuation. He added that while Buffett often mentions discounted cash flows, in all their years of working together, he had never actually seen Buffett calculate one. Buffett humorously responded that some things are best done in private!

To be clear, the author of this article has plenty of models and spreadsheets, but they are never the starting point. The first priority is to assess the quality of a business and its management before even beginning to analyze the numbers.

In reality, most investors buy into a narrative. Take the dot-com boom, for example. Every tech company was considered golden, and few investors scrutinized the CEO's ability to deliver on their promises. It's backward, upside-down thinking. Why do people speculate this way? They arguably deserved to lose money when the bubble eventually burst.

We see parallels today with AI companies. Any business associated with artificial intelligence is trading at a huge premium because speculators are buying into a narrative rather than asking the tough questions they should be asking.

Consider this: Xerox PARC (Palo Alto Research Center) was established by Xerox Corporation in 1970 and was responsible for pioneering many groundbreaking computer technologies. These innovations included the graphical user interface (GUI), the computer mouse, Ethernet networking, laser printing, and the first personal computer, known as the Alto.

Imagine the excitement surrounding Xerox at the time. The narrative was compelling: a gathering of some of the brightest minds in technology, creating revolutionary inventions. Who wouldn’t want to invest in that story?

Yet, Xerox failed to capitalize on its own inventions.

Take the GUI, for example. Despite its potential, Xerox did nothing to bring it to market. Instead, Steve Jobs, inspired by the work being done at Xerox PARC, borrowed its ideas. He developed the first commercial GUI for Apple’s LISA computer in the early 1980s. While Jobs didn’t invent the GUI, he made it commercially available. However, he was focused on hardware sales rather the developing a software business, so his GUI was exclusively available on Apple machines, a move aimed to propel the sale of his computers.

This approach left an opening for Bill Gates, who recognized the power of the Apple GUI and developed Windows 1.0, launching it in 1985. Unlike Jobs, Gates focused on software and made his GUI accessible to anyone, regardless of the computer they were using. This strategy led to the widespread adoption of Microsoft’s operating system, which by 1994 held more than a 90% market share.

The GUI became the launchpad for both Apple and Microsoft to become two of the most successful companies in the world. However, neither company invented it. The innovator, Xerox, did nothing with its creation, and as a result, its fortunes declined. Once a member of the esteemed Nifty Fifty, Xerox is now a shadow of its former self.

‘A good idea in the hands of a mediocre team is like giving a bottle of champagne to a child. They don’t appreciate it and don’t know what to do with it. But give a mediocre idea to a brilliant team, they’ll either fix it, or throw it away and come up with something better.’

Ed Catmull

At the risk of repeating myself, it’s not the company, the idea, the revolutionary innovation, or the target addressable market that matters most. It’s all about the quality of management having the foresight and ability to commercialize the opportunity. In other words, invest in the management.

Finding Exceptional Management

Great CEOs are born, not made. They possess distinct character traits that set them apart.

One key personality trait that exceptional leaders share is the courage to be unconventional. They understand that to outperform others, they must take a different approach from the rest.

They all embrace a decentralized approach to management, avoiding hierarchical bureaucracy creeping in as their business scales up. They also nurture talent by focusing on promotion from within which they find is preferable to rolling the dice with external hires. They encourage employees to think like owners and to engage in helping it to evolve.

Frugality, is another common trait among exceptional leaders, often leading to superior corporate cost control. This principle dates back to Benjamin Franklin’s adage, "A penny saved is a penny earned," and is evident in the practices of modern entrepreneurs.

Take Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon. His commitment to cost consciousness was clear from the outset, requiring employees to construct their own ‘door desks’ by attaching four table legs to a simple wooden door. Bezos is always looking for ways to cut costs, encouraging employees to contribute ideas. One such idea was to remove light bulbs from vending machines in Amazon offices, resulting in an annual electricity savings of $20,000 - truly, a penny saved is a penny earned.

Herb Kelleher’s remarkable 47 years of uninterrupted profitability in the airline industry also highlights the power of frugality. While other airlines offered elaborate meals, Kelleher kept costs down by serving just a drink and a pack of peanuts, which sufficed for most travelers. Instead of expensive tailored uniforms for his crew, he opted for simple polo shirts. Once again, a penny saved is a penny earned.

Another crucial trait of a great CEO is the ability to think long-term. This concept is well illustrated by an anecdote from investor Anthony Deden. During a visit to an Arab date farm, Deden observed the 60-year-old farmer zealously planting sapling date trees, knowing it would take four decades for them to bear commercially valuable fruit. Despite the fact that he would not see the yield in his lifetime, the farmer was committed to investing his time and resources for the benefit of future generations.

The stark contrast between the mindset of this Arab farmer and a conventional Western corporate leader was not lost on Deden. The average tenure of a public company CEO in the U.S. is little over four years and their incentives are benchmarked against short-term financial metrics. Against this backdrop, do you think that they are motivated to do what’s best for the company and its shareholders for decades to come? Or do you think that it’s more likely that they are focused on doing whatever’s necessary to hit short term remuneration targets to enrich themselves?

‘Show me the incentives and I’ll tell you the outcome’.

Charlie Munger

The fundamental difference was that this Arab farmer was thinking only long-term. He had reaped the benefit of sapling trees that had been planted by his predecessors which were now bearing fruit, and so stewardship of the farm for the benefit of future generations was his goal. His role was not to enrich himself, but to protect, preserve and enhance the farm that he had been trusted to manage so that he could pass it on stronger than when he received it.

A steward of a business is essentially a trustee of assets owned largely by others, the beneficiaries - whether they are partners, shareholders, family members or any other kind of stakeholder. A trustee’s duty is discharged by acting in the best interests of the beneficiaries – that’s the mission.

This mission is precisely what Jeff Bezos outlined in his inaugural shareholder letter, published around the time of Amazon’s 1997 IPO. Bezos stated clearly, "We believe that a fundamental measure of our success will be the value we create over the long term… we make decisions and weigh trade-offs differently than other companies. We make investment decisions in light of long-term market leadership considerations rather than short-term Wall Street reactions." Bezos was not interested in catering to short-term investor demands; he understood that building a successful company is a long-term endeavor requiring an entirely different mindset.

Bezos distinguished himself from other businesses from the outset, and so all the clues were present at a very early stage in respect of Amazon’s leadership. Had an astute investor spotted this, and invested a mere $10,000 at the time of the IPO, that investment would be worth well over $20 million today.

Prem Watsa, Founder, Chairman and CEO of Fairfax Financial Holdings is another exceptional leader. In his 2023 Shareholder letter he writes, ‘Since we began in 1985, 38 years ago, our book value per share has compounded by 18.9% per year (including dividends) while our common stock price has compounded at 18.2% (including dividends) annually. Our success throughout our history, and again in 2023, has come under a decentralized structure with outstanding management… We continue to focus on how Fairfax can survive for the next 100 years, long after I have gone!’

You should begin to see how these golden threads present themselves time and again when analyzing great businesses. The clues are all there, as an investor you simply need to know what you are looking for.

This approach of selecting investments based on the quality of management has been used to great success, not only by Phil Casset, but by many others over the years. For instance, Henry Singleton, an exceptional CEO in his own right, was an early investor in Apple. This was a time when the personal computer industry was in its infancy, with hundreds of start-ups entering the market, most of which failed. When asked how he chose to invest in Apple, Singleton simply said he was impressed by Steve Jobs, who appeared to be a man on a mission, fully committed to achieving his long-term goals. For Singleton, Steve Jobs' passion and vision distinguished him from others in the industry - accordingly, he invested based on evidence of the management traits required to achieve results, rather than investing in the business itself.

Steve Jobs later distinguished CEOs on the basis of a select few being missionaries, while most he considered to be nothing more than mercenaries. Does this not confirm all that has been discussed in this post?

Once again, we see that people are more important than the company. The lesson for you and me is that we should only invest in missionaries with the correct personality traits. Avoid the mercenaries and those not up to the job.

This brief overview only scratches the surface of how investors can identify exceptional CEOs. There is so much more to discover. If you enjoyed this post, you’ll love the author’s book, which delves into over 50 chapters exploring the golden threads woven through the fabric of well-run businesses and their exemplary CEOs:

Conclusion

Running a business is more art than science. Unfortunately, most CEOs lack the requisite artistic ability and so instead adopt a scientific mindset. Their approach to management is to follow a conventional formula. Rather than adapting to evolving circumstances and assessing all available options as they arise, they rigidly adhere to a predefined playbook. This significantly impairs the ability of the company to achieve its full potential, transforming it into a management bureaucracy.

For instance, capital allocation decisions should be guided by careful consideration of opportunity costs, yet most CEOs default to distributing capital according to a rigid progressive dividend policy, regardless of circumstances. Buffett and Bezos, who practice what they preach, have both argued that paying a dividend is often the wrong choice, yet many CEOs blindly follow their playbook without thinking critically. They replace the need for management to exercise discretion, with a codified approach that avoids the need to make difficult decisions. Do you want someone like that running a company in which you are invested?

Frankly, the way in which the average CEO manages a business is like trying to create a work of art using a 'paint-by-numbers' method, revealing their lack of genuine mastery in the art of business. Continuing the metaphor, while anyone can hold a paintbrush and apply color to a canvas, few can create a masterpiece. This is why 95% of companies are mediocre at best.

Our job as investors is to discover the true artists. As investors, we’re not looking for the next Apple; we’re looking for the next Steve Jobs. We’re not interested in a retailer with a stellar five-year historic record, which means nothing if management changes; we’re searching for the next Sam Walton.

I like people who make me think and your article did just that. I will check out Alpha Group. I hope I can further add to the discussion as well. Have to think more about it. Some CEO’s who originally may look good turn out to be disasters. They are few and far between. Thanks.

Great article. Phil Carret also wrote another book “Money Mind at 90,” which also very good.

Anyone care to name any up and coming CEO who may be not in the spotlight but could be the next Steve Jobs?