S&P500 Passive Investing | Blind Money

The 2022 Market Crash Was A Pivotal Moment For Passive Investors

Anyone can successfully walk in a straight line with their eyes closed for a short while. But push your luck too far and sooner or later you are liable to step under a train or in front of a car. This is a perfect metaphor for passive investing.

When the S&P500 compounds at 16.6% CAGR for a decade, as it did from 2011 to 2021, then passive investing works. But the coincidence of circumstances that brought about that outstanding return have now come to an end as I shall explain. If passive investors expect a repeat of the past decade then I fear that they are in for a rude awakening.

The biblical Joseph effect is apt: 7 years of bountiful harvests were followed by 7 years of famine. 2022 marked the beginning of a painful period for passive investors.

Why Did Passive Investing Work Previously?

1. Riding the Bull

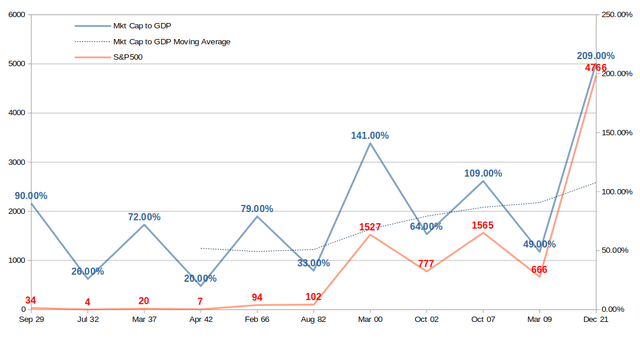

The chart shows the secular peaks and troughs in the stock market over the past century going back to the great depression of 1929 to 1932.

The red line shows the S&P 500 (and equivalent going back in history). Since 1982 it is easy to see the peaks and troughs but due to the scale used it is more difficult to see the early dates. Yes, I should have used a logarithmic scale, I know that, but instead I have added the values of the index in red to enable you to see how the index oscillated up and down at that time.

The blue line is the market cap to GDP ratio for the index (this is one of Warren Buffett's favourite macro-economic metrics).

Note how the peaks and the troughs align perfectly. Also note how over priced the market was at the close of 2021 (a 209% market cap to GDP ratio was unprecedented).

This article reveals what drove the market to being so vastly over priced and, more importantly, why the investment community should not expect it to return to such lofty heights anytime soon.

When a bull market runs away with itself in this way, it is almost impossible not to make money.

In fact, money was so easy to make over the decade to the end of 2021 that every monkey thought he was a financial expert. Dumb money flowed into passive funds in record quantities. Very few of the primates in the market stopped to consider whether this was sustainable. Still fewer possessed the skill or expertise to understand what was happening.

2. Why Did The Bull Run Rampant?

As an investor you must understand that your returns will depend on a few inter-related factors. These are:

growth in sales (S&P500, 2011-21, CAGR +3.4%)

changes in profit margins (S&P500, 2011-21, CAGR +3.8%)

price multiple that the market is paying for those margins (S&P500, 2011-21, CAGR +5.8%)

dilution or accretion from changes in the share count (S&P500, 2011-21, CAGR +0.7%)

dividend yield (S&P500, 2011-21, 2.3% average per annum)

In combination, over the decade to December 2021, these factors resulted in a total return for investors of 362.6% (16.6% CAGR) as the index climbed from 1,257.6 on 31st December 2011 to 4,766.18 ten years later.

Now you can see why the monkey’s all made good money. The question that you will want answered is, ‘why did each factor behave in this way and are we likely to see it repeated going forward?’

Let’s deal with each in turn.

i. Sales Growth

During the decade to 2021, S&P500 sales growth was 3.4% CAGR so nothing spectacular or unusual there, although it was stronger than the average GDP growth rate over the same period (see chart below - ignore the anomalous spike at the end which is the Covid19 hit and subsequent release of pent up demand). The difference in sales growth to GDP is largely accounted for by expansion in overseas earnings generated primarily by the US tech sector.

Going forward what are we to expect in terms of sales growth?

First, we should note that Global GDP is expected to contract significantly due to the anticipated 2023 recession. Central banks were very wrong about inflation being transitory and their delay in tightening fiscal policy proved costly. To make matters worse, the Russian invasion of Ukraine impacted global commodity markets and pushed inflation to 40 year highs. Central bankers finally woke up and the rate curve steepened very rapidly at the short end. The repercussions are yet to be felt but recession is almost inevitable.

In the short term, inflation means higher prices which translates into higher revenues in dollar terms, even if the quantity of goods and services remain unchanged or even falls. As such, the negative impact on the top line takes a time to feed through the numbers and will be masked by an initial improvement in the first instance. This was born out in fact during 2022 when S&P500 sales in Dollar terms rocketed 11.4% due to the inflation price effect. Now we need to brace for the contraction as the inflationary price effect drops out of the numbers.

Long story short, top line growth at 3.4% as seen in the decade until 2021 is unlikely to be repeated in the next few years. We should expect a top line growth dip and perhaps even a contraction in the near term.

ii. Profit Margins and Price Multiples

Over the past 70 years average net profit margin of the S&P500 constituents has been around 6.5% as the chart below demonstrates.

However, by the end of 2021, look how profit margins shot up to an unprecedented 13.4%. We’ll examine why this happened, and is unlikely to be repeated, shortly.

The chart also shows the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio (commonly known as CAPE, Shiller P/E, or P/E 10 ratio) which is price divided by the average of ten years of earnings, adjusted for inflation. Using CAPE paints a more accurate picture when analyzing a century worth of data. This number was also very elevated at 40, second only to the 44 reading at the peak of the dotcom bubble.

Much of the net margin expansion in recent years can be attributed to the tax cuts introduced by President Trump (TCJA) in 2017. When these cuts occurred every company in the US received a boost of 21.5% to their bottom line (profit after tax increased from 65c to 79c in every Dollar as corporation tax was slashed from 35% to 21%). It was a political stunt which caused the market to rally and will not be repeated.

The margin expansion was further exacerbated by central bank generosity (ZIRP policy). From 2009 until 2022 money supply expanded rapidly through quantitative easing and cash was available at close to zero cost. When financing costs are negligible, net profit gets a boost.

The problem now is that the TCJA tax cuts may be undone by the Biden administration in order to finance public debt which is out of control. This would have the opposite effect on corporate profit margins.

Then, as noted in the previous section, we have the issue of raging inflation and higher interest rates, both of which will increase funding costs and so adversely impact margins. The Fed is not done hiking rates and the pain of recent rate hikes is still to be felt in the economy (there is always a lag until fixed term debt matures and needs to be refinanced). That will eat into profit margins and curtails growth.

By the end of 2022, the S&P500 profit margin fell from its peak 13.4% to 11.3% (that’s a 15.7% contraction) and it is still well above long term trend. Anticipate single digit margins in the years ahead, we have further to fall from here.

iii. Multiples

The index was capitalized at 13x earnings at the end of 2011, a number that had ballooned to 23x earnings by the end of 2021. This was the biggest contributor to shareholder returns over the decade.

Admittedly, having the index capitalized at 13x earnings in 2011 was well below average. Companies were recovering from the credit crisis of 2008. As such, from a low base, multiple expansion was to be expected. But the historic average multiple is somewhere closer to 18.0x and so the market overshot reasonable valuation levels. I will explain what drove multiples to expand so aggressively in section (iv) below.

By the end of 2022 margin contraction had occurred and the S&P500 was now trading at 19x earnings (still well above the long term average). Please bear in mind that the premium that investors are prepared to pay to be invested is entirely dependent upon anticipated future returns. As already discussed, top line growth prospects don’t look good and margins are contracting with further to go. Against this backdrop do you think that price premiums are likely to expand or contract further?

iv. Changes in Share Count

This is a fascinating area on so many levels and helps to explain how price multiples, discussed in the last section, became so over inflated.

I have borrowed from an article that I recently published on stock based compensation abuse which is very relevant here.

Deutsche Bank Global Research revealed that one of the key drivers of the stock market rally since the financial crisis of 2008 was stock buy-backs.

The chart below demonstrates who has been buying equities in the US and it is clear to see that “Non-Financial Corporations” (read companies buying back their own stock) is the driver.

Over the 10 year period 2009 to 2019 corporate buy-backs totalled $4 trillion USD. Share repurchases accelerated over the period, as can be seen from the chart. By 2022, for the first time in a single year, S&P500 constituents consumed $1 trillion USD of earnings in buying back their own stock.

As a side note, be aware that a trillion dollars of repurchased equity amounted to 2.8% of the $36 trillion average market capitalization of the S&P500 during the year. The number of shares outstanding only declined by 1.1%. So what happened to the remaining 1.7%? That’s the dilution that comes with the abhorrent behaviour of corporate executives who advise shareholders to ignore Stock Based Compensation (SBC) because it’s not a cash expense.

Aside from the dilution, which is damaging enough, much of this repurchasing happened at over inflated prices which is generally a sign of executive level incompetence. Paying the wrong price for repurchases destroys shareholder equity (the math is beyond the scope of this article) which is why Warren Buffett only repurchases Berkshire stock when it falls below what he perceives to be intrinsic value (if you want to better understand the economics of buy-backs, please click here).

Know this, if you buy shares in the market that are capitalized at 30x earnings then you will achieve a 3.3% earnings yield, simple math. That doesn’t meet the hurdle rate of any intelligent investor when the risk-free 10 year treasury yields 4% and inflation is eroding the value of money at over 6%. When a company repurchases its shares at 30x earnings it is allocating shareholder capital at the same paltry 3.3% earnings yield! Not only is this destroying shareholder equity due to an over-payment for the securities but it also dilutes down the return on capital that the company is able to achieve via its core business activity. Why use corporate capital to achieve a 3.3% yield when your return on capital invested in the business itself is a double digit number? This is exactly what Apple, Meta and others have been doing year after year in what I refer to as “pumping air into the bubble”.

Stock repurchases are often dressed up as returning capital to shareholders, but they are rarely anything of the kind. In recent times they are used to offset dilution due to SBC in order to enrich the insiders at the expense of the shareholders. Don’t be fooled (to understand more about the dangers of SBC, please click here).

This is relevant to the bull run of the past decade because, to a very large extent, it was fueled by artificial demand for stock, at over inflated prices, as a result of nefarious SBC activity.

If corporations are spending 65% of earnings repurchasing stock regardless of price, is it any wonder that the earnings multiple kept climbing and climbing over the past decade? The fact is, this aspect of modern corporate finance distorted the market enormously. This is why a refer to it as “pumping air into the bubble”, allow me to explain:

The S&P500 calculates weightings based on the market cap of constituents. So over-priced corporate buy-backs inflate the market cap and result in a larger index weighting. Passive funds emulate the index by mirroring weightings, so they allocate more dumb money to those companies engaged in over-priced buy backs. This disproportionately inflates the market cap of those companies still further. Then the company repurchases more of its own stock, regardless of price, and the cycle repeats. Now you know how, at their peak, the FAANG stocks ( META 0.00%↑ GOOG 0.00%↑ NFLX 0.00%↑ AAPL 0.00%↑ AMZN 0.00%↑ ) had a weighting that accounted for over 27% of the S&P500 despite being only 5 companies out of the 500 in the index.

What this meant was that 27% of all money flowing into S&P500 passive funds was being pumped into these five companies. So these were the companies in which passive investors were most exposed to. As explained, passive investing amplified the market distortions that were occurring. Times were good from 2011 to 2021 as the FAANG stocks accounted for 29.3% of all S&P500 gains, but when the bubble burst in 2022 these five companies accounted for 46.3% of the index loss and the passive monkeys got burned badly.

Three points are worth making here:

First, US corporations introduced $1 trillion of ‘artificial’ share purchasing demand to the market in 2022 through buy backs and the index still fell 19%. How much further it would have fallen without this market distortion?

Second, with sales and margins contracting as discussed above, profits will be negatively impacted. Overlay a recession on this fact set and profits are likely to be squeezed further. If this ‘artificial’ demand that has existed in the market for the past decade dries up (or significantly contracts) because companies have less profit to squander on repurchases, how will the supply/demand equilibrium be impacted and where might that take the S&P500?

In his recent State of the Union speech, President Biden announced a quadrupling of the 1% tax on stock buybacks that took effect in January 2023 in an effort to encourage businesses to allocate capital to investing in growth. As such, buy-backs will be significantly curtailed in future and so this “pumping air into the bubble” effect will not drive index gains in future as it did over the last decade.

v. Dividend Yield

There is nothing remarkable to say about dividend yields which averaged 2.3% over the decade to December 2021. Dividends remained very stable over the period and are unlikely to have a dramatic impact one way or another on changes to shareholder returns going forward. In a recession dividends are often cut back and so a small negative effect ought to be anticipated.

Conclusion - where next?

Let us assume that the top line growth and share count accretion revert to the average of the decade to December 2021 at 3.4% and 0.7% respectively (optimistic). Let us also assume that margins stabilize at 11.3% (optimistic) and that the index capitalization remains at 19.2x earnings (optimistic). With funding costs way higher than in recent years and input costs well up due to inflation, let us assume that dividend yields are shaved to 2%. Under these circumstances the investor will achieve 6.1% compound returns. It would put the S&P500 at 4225 next year. In the near term, this is probably the best that an investor could hope for. However, with the risk-free rate at 4% on the 10y Treasury, equity risk premium hovering around 5% and inflation well over 6%, does this meet the hurdle rate for an intelligent investor? It is certainly well below the 16.6% CAGR enjoyed by index investors in the period 2011 to 2021.

Another scenario may be that top line growth slows to 2.5%, share count remains unchanged, profit margins contract to 8% (29.2% decline from 11.3%) and the index is capitalized at 15x earnings (21.9% decline on 19.2) due to the slow down and resulting recession. At the same time dividend yields drop to 1.8% as they did in 2022. If this situation plays out then an index investor will be looking at a total return loss of 29.1% (after dividends) from today’s levels. That puts the S&P500 at 2823.

So we have a range for the S&P500 in the next 12 months from 2823 to 4225, from today’s level of 3982. This suggests an asymmetric skew to the downside. In other words, for a passive investor, the odds are not favourable and even the best case scenario is far from good.

Passive investing exploded in popularity over the decade to December 2021, becoming more dominant than active investing for the first time. This was the result of the fly-wheel effect which I have explained above which is highly unlikely to be repeated.

Now is the time to invest wisely. In my humble opinion active investment is the only way to navigate the choppy waters ahead.

While blindly investing in the market as a whole worked previously, for reasons given it is unlikely to work well in coming years. Now is the time to cherry pick value stocks.