The Fallacy of Price-Centric Investing

Schrödinger's Cat in Finance: A Stock Can Be Both Expensive & Cheap

Traditional value investors, influenced by the teachings of Benjamin Graham, have long prioritized purchasing stocks at a discount to their intrinsic value, attempting to capitalize on market inefficiencies. The theory, which is fundamentally sound, involves an arbitrage trade between a security's price and the underlying value of the business. Over time, the price and intrinsic value are expected to converge—ideally through an increase in the share price rather than a decline in intrinsic value. In essence, if a business performs well, its stock will eventually reflect that success.

Even when applied correctly, this theory is inherently challenging as markets have a tendency to remain irrational for extended periods of time. Contrarian investing, after all, involves seeing things differently from the majority, which creates the opportunity to buy the shares at a discount to fair value. This approach often requires patience, as it can take time to confirm whether your analysis was correct and for the market to align with your perspective.

“Investing is a business where you can look very silly for a long period of time before you are proven right.”

Bill Ackman

A share that is down 90% from its peak, is a share that was previously down 80% and then halved in value again! In other words, if something seems too good to be true, it often is. Just because a stock appears cheap doesn't mean it will recover. Even if a company’s stock is down 99%, you can still lose 100% of your investment if the business's value continues to decline toward zero.

Benjamin Graham's 'cigar butt' approach to investing involved finding stocks so cheap that they're like a discarded cigar butt with one last puff left - not great quality, but possessing marginally more value than the market ascribes to them. Graham aimed to profit from the small upside when the market eventually recognized the stock's true value. Rather than being a ‘buy and hold’ strategy, it involved moving capital from one cigar butt to another, trying to extract a little value from each along the way.

“Far more money has been lost by investors preparing for corrections, or trying to anticipate corrections, than has been lost in corrections themselves.”

Peter Lynch

As John Maynard Keynes observed, true investing is about forecasting the yield over the life of an asset, while speculation centers on predicting market psychology. Graham’s value investing approach, particularly his ‘cigar butt’ style, blurred the boundaries between the two.

Charlie Munger ardently disliked speculative trading that relied on the changing sentiment of a largely irrational investor base, so he persuaded Warren Buffett to move away from Graham’s methodology. The focus of Berkshire Hathaway shifted to prioritizing quality over price and aiming to remain invested for the long term, in exactly the same way that one would if taking a stake in a private enterprise.

Although Berkshire Hathaway acknowledges the academic validity of Keynes’s views on true investing, its approach does not involve assigning a precise value to a business using discounted cash flow models. As Buffett has remarked, “Intrinsic value is the present value of the stream of cash that’s going to be generated by any financial asset between now and doomsday. That’s easy to say and impossible to figure.”

Buffett and Munger have always suggested that there is no magic formula, model, or spreadsheet that can definitively determine a company’s worth because value is not an objective measure. A business is only worth what someone else is willing to pay, making it entirely subjective and subject to constant change. In other words, investing is an art, not a science.

Munger captured this idea well when he remarked that if you see an overweight man walking toward you, it's not necessary to weigh him to know he is overweight. Similarly, it's often easy to distinguish between a good and a bad investment. With practice and experience, an investor can quickly recognize the qualities of each type.

A Company Can Be Both Expensive & Cheap

Companies like Amazon and TCI have often appeared overvalued when assessed using traditional earnings metrics. However, those with deeper insight recognize that in both cases, visionary CEOs deliberately sacrificed short-term earnings, making these companies seem more expensive than they actually were.

Jeff Bezos, for example, took inspiration from John Malone at TCI. Malone understood that high earnings would lead to substantial corporate tax liabilities. He intuitively recognized that a better approach was to suppress earnings by investing in growth. By optimizing strategic OPEX and CAPEX spending, Malone was able to accelerate compounded growth on capital that would otherwise have been lost to the tax man (explore John Malone's approach in more detail).

Quarterly and other short term numbers are certainly not the ideal way to evaluate a business like Amazon. The key metrics to focus on are customer acquisition and retention. As stated above, the value of a business is the discounted value of future cash flows, so the focus is not on current earnings but on optimizing future earnings. Each new customer significantly increases future cash flows, which compounds over time. When you calculate the net present value of those future cash flows, you see a company that is consistently growing in value, regardless of recent quarterly earnings, which may be depressed due to investment in acquiring more customers. It’s all about the lifetime value of the average customer multiplied by the number of customers!

When valuing a company based on earnings multiples, if the denominator (earnings) is artificially low due to heavy investments in growth, the metric will be misleading. The key is to separate growth investments from the spending necessary to maintain operations. This reveals the true earnings power of the business, which is the adjusted figure that should be used as the denominator for valuation purposes. This is why Malone invented the concept of EBITDA, and Buffett uses his own adjusted profit number which he calls ‘owner earnings’ (defined in his 1986 shareholder letter for those interested in further reading).

For years, while the media and equity analysts criticized Amazon for being too expensive based on an apparent earnings multiple exceeding 70x, it was never truly trading at that level. Savvy investors recognized this, invested, and enjoyed substantial returns.

This illustrates how companies like TCI and Amazon can simultaneously appear expensive yet, in reality, be fairly valued or even cheap. In the words of Hamilton Helmer, a great business is one having, “a set of conditions creating the potential for persistent differential returns”. Said differently it’s all about taking the long-term view.

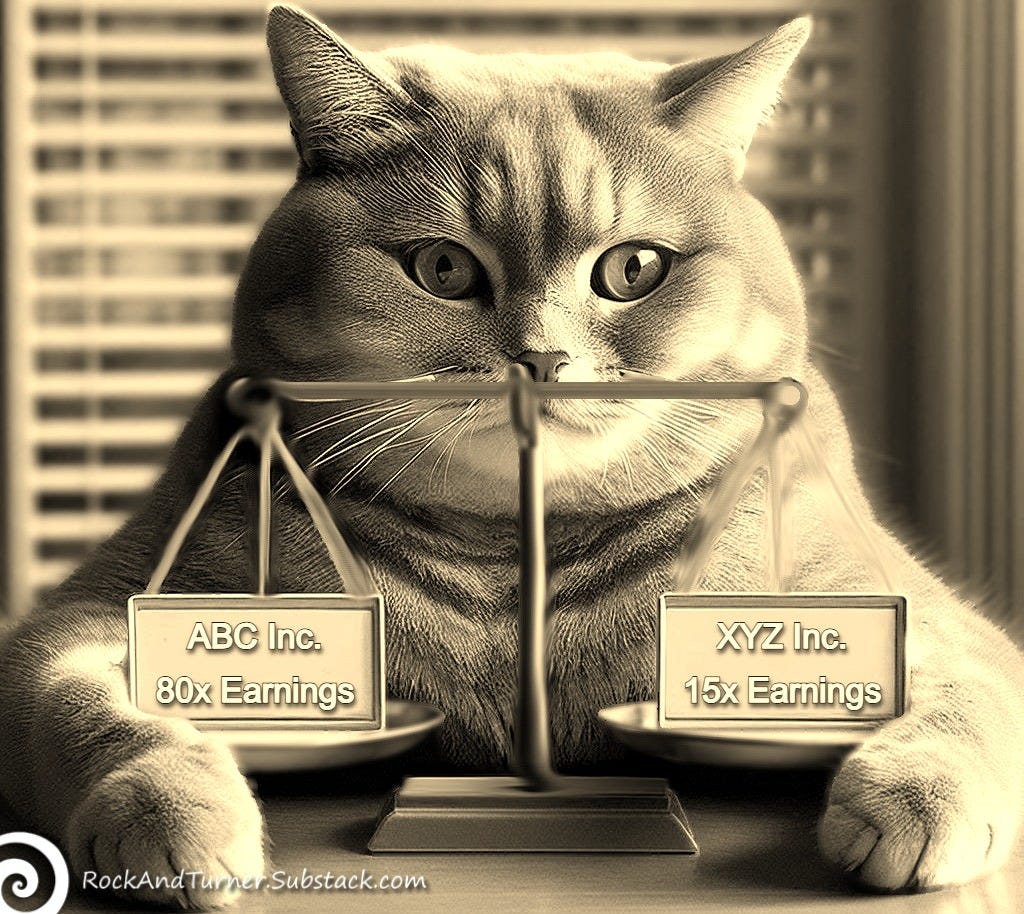

However, some companies do genuinely have high earnings multiples and may seem expensive at first glance. But are they really?

Paying a seemingly high price for a high-quality business can be a wise decision if a high quality business continues to execute its growth strategy effectively.

The Nifty Fifty of the 1960s and 1970s further illustrate this point. These were a group of high-growth, high-quality companies regarded as "buy and hold forever" stocks. During that era, investors were surprisingly willing to pay prices equivalent to 50x, 80x, or even 100x earnings.

Yet if an investor had constructed an equally weighted portfolio of all the Nifty Fifty companies and purchased them at their peak earnings multiples in 1972, holding them for a quarter of a century until 1998, that portfolio would still have generated an annual shareholder return of nearly 12.5%. With such a healthy return over a sustained period, can anyone claim that these companies, with eye-watering earnings multiples in 1972, were overpriced?

Many of these companies, such as Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, Walt Disney, and Johnson & Johnson, continue to thrive today (for more detail on the Nifty Fifty see here).

To further illustrate this point, Ash Park and Refinitiv Datastream (a Reuters company) conducted an insightful analysis. Between 1st January 1973 and 30th September 2019, the MSCI World Index delivered a compound annual growth rate of 6.2%. The study focused on a selection of well-known companies that operated throughout this 46-year period. By examining their current share prices, the researchers calculated the earnings multiple an investor could have paid for each company in January 1973 to achieve a 7% CAGR, thereby outperforming the MSCI Index. The following chart displays their findings.

Although L’Oreal never actually traded at such a high valuation, an investor could have paid 281x earnings and still outperformed the market with an annualized 7% return. Similarly, an investor could have paid 230x for Lindt, 126x for Colgate and 100x for Pepsi and each would have delivered the same 7% average return over the 46-year period.

The issue, quite simply, is that earnings metrics are backward-looking: all of our knowledge is based on the past, while all our investment decisions are about the future - a significant challenge for investors.

This illustrates that valuations based on a single moment in time are often unreliable without considering the many other factors that drive investment returns. As Buffett notes, “Value investing and growth investing are one and the same. Growth is part of value. Part of the same equation. Returns on incremental capital are the key.”

Some readers might argue that 46 years is an unusually long period, potentially skewing the results. So, let’s compress the time frame to just five years to demonstrate the same principle.

Take Netflix, for example. In 2015, it was generating earnings per share of only 9 cents, with a staggering valuation of 554x earnings. Despite this incredible valuation, an astute investor may have recognized its rapid growth and considered its future earnings potential. By 2020, Netflix's earnings per share had soared to $5.93 which, if taken against the 2015 share price, would have implied a five-year forward earnings multiple of just 8x - a true bargain!

In contrast, British retailer Marks & Spencer generated 31 pence per share in 2015 and was valued at a seemingly modest 15x earnings, which many would have considered cheap compared to the broader market. However, mediocre management and declining business led to a sharp drop in earnings. By 2020, Marks & Spencer was earning just 1.2 pence per share, revealing that its 2015 five-year forward earnings multiple had actually been a staggering 380x - a classic value trap!

The Magic Ingredient: Time

From Amazon to Coca-Cola and L’Oreal to Netflix, it seems that a company can be both expensive and cheap simultaneously. We've also seen how a company that appears cheap, like Marks & Spencer, can turn out to be incredibly expensive. This phenomenon is the economic equivalent of Schrödinger's cat - except, instead of opening a box to determine whether a company is cheap or expensive, only time will reveal the answer.

“Time is the friend of the wonderful company, the enemy of the mediocre.”

Warren Buffett

Time therefore becomes the magic ingredient for an investor for three primary reasons.

First, as time passes, inflation drives prices higher, which, all else being equal, boosts both the top and bottom lines of the income statement. Even if the unit economics of the business remain unchanged, this will cause forward multiples to trend lower over time. Additionally, inflation causes certain real assets to appreciate in value while debt is effectively devalued, thereby strengthening the balance sheet and enhancing the valuation of the business.

Second, unlike other assets, an equity stake in a business has the unique ability to compound in value over time if the company is able to reinvest earnings at accretive rates of return. (For a full understanding of the power of exponential growth and the folly of interrupting compounding, including a mathematical proof, see here in the context of extracting capital to pay dividends.)

Third, there is a common misconception that paying a high multiple permanently impairs investment returns, as any multiple contraction is believed to negate economic gains. However, let’s examine this mathematically using book value multiples. For investors, the effective earnings yield is the Return on Equity (RoE) divided by the price-to-book (P/B) multiple paid for the investment. However, as a company allocates capital to growth, retained earnings are reinvested by a company at book value. Consider a hypothetical scenario: you pay 4x book value to invest in a growth company achieving a 20% RoE. For the sake of simplicity, assume that this company doubles its book value annually. In the first year, the shareholder earns an effective yield of 5% (20% ÷ 4). By the second year, the book value per share has doubled. While 4x was initially paid for half the total book value, the other half has been added at book value, reducing the average premium to 2.5x. So in the second year the earnings yield increases to 8% (20% ÷ 2.5). Over time, the premium initially paid continues to dilute as book value grows, tending towards one (zero premium). As a result, the investor’s earnings yield will tend towards the company’s RoE, eventually nearing 20%. This demonstrates how the impact of paying an initial high multiple diminishes with longer holding periods.

In combination these three factors (time, inflation, compounding and the dilution of premiums paid) work together to produce an outstanding investment result.

“Time in the market beats timing the market.”

Ken Fisher

None of this was lost on the intellectually astute Charlie Munger. In his 1994 ‘The Art of Stock Picking’ speech, he declared that, “Over the long term, it's hard for a stock to earn a much better return than the business which underlies it earns. If the business earns 6% on capital over 40 years and you hold it for that 40 years, you’re not going to make much different than a 6% return, even if you originally buy it at a huge discount. Conversely, if a business earns 18% on capital over 20 or 30 years, even if you pay an expensive looking price, you’ll end up with a fine result.”

The mathematical reasoning behind this is straightforward. When an investor buys a fractional share in a great company, it often trades at high multiples of both earnings and book value. However, when a company reinvests its earnings back into the business, it does so at book value. Now, consider a company that compounds its growth at an annual rate of 18%. Such a company will double in value roughly every four years. After four years, each dollar invested in the company will be worth two dollars. The initial dollar was invested at a multiple of book value, while the second was invested at book value. This dilutes the premium paid on the equity held by a factor of two. After another four years, the company doubles again, and now each dollar initially invested is worth four, with three of those invested at book value. Now the premium paid on the equity held is diluted by a factor of four. It's easy to see that after twenty or thirty years of holding the position, the premium initially paid becomes almost insignificant.

These benefits of compounded growth are optimized only when all earnings are reinvested at similar marginal rates of return to that being achieved on existing capital. Companies that distribute earnings as dividends or use them to repurchase stock - especially to offset dilution from stock-based compensation - significantly impair the compounding potential of the business (see Value Investors Are Barking Up The Wrong Tree). Allocation of capital is a matter that should always be determined by assessing opportunity cost and, in the case of a quality company, reinvestment of earnings is usually always the best choice.

This is why Munger convinced Buffett to deviate from his Ben Graham approach to value investing. Under the influence of Munger, the modus operandi of Berkshire Hathaway shifted to buying quality and holding for the long term to enjoy the benefits of compounding. Buffett has owned American Express stock since 1965 and still holds it today. He has held Coca-Cola stock since 1988. Morgan Housel points out that this pivot, and the need for time to work its magic, is why 97% of Warren Buffett’s net worth was generated after his 65th birthday.

Terry Smith, the successful British fund manager has three rules of investing:

Invest in Good Companies (the quality element)

Don’t Overpay (the price element)

Hold and Sit on your Hands (the time element)

It is no coincidence that all great investors seem to settle on the a very similar approach!

One further advantage of the 'buy and hold for the long term' strategy is that it naturally steers investors away from cyclical industries, short-term trends, and companies that depend on constant innovation for survival, like those in the pharmaceutical sector. With a bias towards stability, this approach reduces the need to frequently switch investments, minimizing the pressure to chase the next big trend or discovery. As an added benefit, it avoids the frictional costs associated with trading!

This explains why Warren Buffett has generally avoided tech businesses and instead invested in consumer staples like Coca-Cola, Gillette, and See's Candy. These resilient businesses generate strong returns even in challenging economic conditions. Apple has been the exception, although Buffett was not an investor during the tenure of Jobs which was the period of revolutionary product innovation. Instead he invested well into Tim Cook’s tenure as CEO by which time Apple had largely pivoted away from relying on product innovation and sought to generate much of its income from a more stable ‘rent extraction’ model.

Does Quality Always Trump Price?

Twenty-four years ago, in March 2000, Cisco Systems was the most valuable company in the world, boasting a market capitalization of $546 billion. This valued it at more than the rest of the Canadian stock market combined. Nearly twenty-five years later and its market capitalization today is only $199 billion.

So, what went wrong for Cisco? The surprising answer is nothing. During this period, Cisco’s annual revenue grew from $12.5 billion to $57 billion, and it turned a loss of nearly $1 billion into a profit exceeding $13 billion. In other words, the decline in the share price was not caused by a deterioration in the unit economics of the business. The company is stronger today than ever. The issue was that investors in 2000 paid irrationally high prices for Cisco shares, prices that were unsustainable given the company's fundamentals, both then and now.

Because Cisco was not profitable in 2000, earnings multiples are unhelpful, so let’s focus on sales multiples. In April 2000, Cisco reached an enterprise value-to-sales (EV/Sales) multiple of 27x, compared to a historical average of 6x and today's ratio closer to 3x. This means that despite a fivefold increase in revenue, margin expansion, and a significant reduction in share count due to buybacks, the value created was reduced by 89% due to multiple contraction.

Put differently, Cisco shares may have been worth closer to $8.70 in 2000, the same level they traded at two years earlier in 1998. Investing at that price would have generated an annualized return of 7.8% against today’s share price of $49, a reasonable yet not exceptional result. But during dot-com mania, irrational exuberance led investors to pay $79 for a share effectively worth $8.70. Those who sold at that peak locked in more than a quarter-century's worth of returns in advance, while those who bought at those inflated prices are still feeling the effects of that premium. For every winner, there's a loser!

A similar scenario unfolded with Microsoft around the same time, and more recently, we’ve seen history repeat with companies like Tesla and NVIDIA.

This phenomenon isn’t confined to tech companies. Walmart experienced something similar, where irrational exuberance drove its share price up rapidly, and it took more than 13 years for the intrinsic value of the business to catch up (see below).

In short, price does matter. Overpaying for a business may eventually be corrected over time, but the opportunity cost during that waiting period can be enormous.

Conclusion

Phil Fisher wisely noted, "the stock market is filled with individuals who know the price of everything, but the value of nothing." His point is that focusing too much on finding cheap stocks can lead investors to overlook the importance of quality.

However, when seeking out quality investments, you are likely to come across analysis claiming that these companies are too expensive, either relative to their peers or against historical earnings multiples. Yet we have seen how an ostensibly expensive investment may turn out to have been a veritable bargain.

Don’t be influenced by the white noise emanating from Wall Street either about ‘over bought’ or ‘over sold’ companies. Remember that sell-side equity analysts are products of a commercial system, trained on text-book theory rather than real world experience, and paid to produce research that drives investment activity, not to ensure accuracy. If sell-side analysts truly understood the market, they would be buying stocks themselves rather than selling advice!

As the findings in this post show, investing in stocks simply because they have low valuations is not a formula for success. A stock may have a low valuation but an even lower intrinsic value. Similarly, buying a quality business without considering valuation is also a mistake as paying too high a price results in much of the future upside being given away in the purchase price. It is important to find a quality company at the right price.

To sum it up, Munger famously said that it's better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price. But I prefer Buffett’s interpretation: "You can have a wonderful business without it being a wonderful stock. But it's quite another story to have a wonderful stock without having a wonderful business."

At the end of the day, it’s rather simple. If you invest at a price lower than the present value of future cash flows, you are bound to eventually earn a return exceeding your discount rate. But the further out those cash flows are, the less certain they are, which means paying for a decade or more of continued growth usually goes awry. There will always be exceptions, but it’s survivorship bias to look at microsoft, amazon, nvidia and others with the most exceptional records - and say look, investing at a very high multiple works.

To know what truly works, we have to look at what has worked. There are several answers to that - deep value being one of them, when done well - but as far as I know, no investor was ever greatly successful over multiple decades, holding a significant number of different stocks over that period (to eliminate statistical outliers who just held one or two stocks) without being pretty price-sensitive.

Even Buffett, Mr “great business at a fair price” has rarely ever bought at more than 15x underlying earnings. Indeed Todd Combs says the first of several questions they ask when they sit down together is “which businesses in the S&P 500 are trading at less than 15x normalised earnings.”