The Next 10 Years: S&P500, Gold, Bitcoin?

Where Will You Put Your Money? Why? Does Your Strategy Need To Change?

Two years of extraordinarily strong gains in the U.S. stock market have been followed by chaos, uncertainty and confusion.

"If you're not a little confused by what's going on, you're not paying attention."

Warren Buffett

As investors, what are we to do? Let’s look under the surface and see if we can reveal any clues.

We’ll begin with a fresh look at the S&P 500, but not in the usual way. Instead of measuring it in dollars, we’ll view it through a different lens to gain a better understanding of whether its returns are no more than an illusion.

From there, we’ll zoom out and examine the broader economic backdrop: rising debt, the fraying fabric of globalization, and the silent erosion of fiat currencies. What do these trends suggest about the future of key asset classes?

Most importantly, what does it all mean for you and me, looking ahead over the next 5 to 10 years? Should we be holding cash, bonds, stocks, real estate, gold, or crypto? Stick with me - I think you’ll find the conclusions both surprising and thought-provoking.

Is S&P Growth Simply An Illusion?

At first glance, the S&P 500 appears to be an incredible growth story. In 1970, the index hovered around 92. Fast forward to 2025, and it's reached roughly 5,900 - a remarkable 64-fold increase over 55 years. On paper, that's exponential. But remember, that's in U.S. dollar terms. And dollars, as we know, don't hold their value over time the way gold does.

So what happens when we adjust for the purchasing power of the dollar using gold as our benchmark?

Imagine this: in 1970, you decided to invest $1 into every point of the S&P 500. With the index at 92, you put in $92.

At the time, $92 was equivalent to 2.31 ounces of gold.

Fast forward to 2025, and your S&P500 investment would have grown to $5,900. However, in gold terms, that’s equivalent to only 1.81 ounces at today’s prices.

So while your S&P500 investment makes you feel wealthier in dollar terms, your purchasing power in gold - the universal constant - has actually declined. You now hold less gold than you started with.

The chart below shows on the left axis the value of the S&P500 in dollar terms - the blue line - against its value in ounces of gold on the right axis - the gold line.

This contrast tells a compelling story.

When you view the S&P 500 through a gold-denominated lens, much of what looks like growth turns out to be nominal rather than real.

The chart reveals that there are clear cyclical patterns when we measure equities against gold - Equities dramatically outpaced gold during the tech boom of the late 1990s and early 2000s, but most of the time gold proved to be the superior store of value.

This dual perspective is essential when thinking about long-term wealth. It highlights how monetary policy, inflation, and economic cycles can distort the appearance of growth. Nominal returns are one thing—but preserving real purchasing power is something else entirely.

Let’s look at gold’s own price history:

The chart reveals several distinct eras:

1970-1980: The Great Bull Market - Gold exploded from $35 to $615 (17.5x increase) following Nixon's abandonment of the gold standard in 1971 and the subsequent inflation crises of the 1970s.

1980-2000: The Long Bear Market - Gold declined from $615 to $279 (55% drop) during the Volcker interest rate shock, strong dollar period, and general disinflationary environment.

2000-2012: The Second Bull Market - Gold rose from $279 to $1,669 (6x increase) driven by the dot-com crash, 9/11, financial crisis, and massive monetary stimulus.

2013-2019: Consolidation - Gold traded mostly sideways between $1,160-$1,400 as the Fed began normalizing policy.

2020-2025: New All-Time Highs - Gold has surged from $1,773 to $3,300 (86% increase) amid pandemic stimulus, geopolitical tensions, and renewed inflation concerns.

Now consider this: if, in 1970, you had chosen to simply buy 2.3 ounces of gold with your $92 and held onto it all these years, that gold would be worth around $7,623 today - significantly outperforming the $5,900 you would have gained from investing in the S&P 500.

In the end, the story of the S&P 500 is a tale of two realities - one told in dollars, the other in gold. While the index has soared over the decades in nominal terms, much of that growth has been driven by the declining value of the dollar rather than true increases in purchasing power. When measured against gold, the benchmark reveals a far more modest, and at times even negative, return.

This perspective doesn’t diminish the role of equities in building wealth, but it does highlight the importance of context. Creating wealth isn't a matter of watching numbers climb on a screen, because while portfolio values may rise in dollar terms, the true test is whether those dollars still hold the same power. And over time, that distinction becomes critical.

All fiat currencies are weakening relative to real assets - inflation does that, but so too does a global lack of fiscal discipline. For over 15 years, many governments spent freely while interest rates hovered near zero. That era is over. And for those expecting a swift return to low rates, the outlook may be sobering.

While rates haven’t been this high for the best part of 15 years, they may not be this low again anytime soon.

No matter what policymakers might hope for, the market has the final say - the bond market, in particular, will set the direction for interest rates. As public deficits grow, governments will need to issue more debt. To attract more buyers, bond prices must fall, driving yields higher. It’s straightforward economics.

While central banks can influence the cost of borrowing through monetary policy, this only impacts short-term rates. Corporate investment is typically financed with long-term debt which is pegged to the free floating bond market that is being pushed higher as I shall explain below. Perhaps this dynamic ought to lead us to expect a steepening of the yield curve which will shape our investment decisions.

The U.S. Dollar, Global Flows and Market Distortions

In a globalized economy where the U.S. dollar serves as the world’s reserve currency, every other country finds itself in a peculiar position. They sell goods and services in exchange for dollars and need to hold those dollars to pay for imports. But here’s the twist: ever since the dollar was unpegged from gold, the U.S. has had the freedom to print as much of it as it wants (we’ll come back to this shortly).

Effectively, America's largest net export became paper dollars with no intrinsic value. To keep the global financial system stocked with these dollars, the U.S. had to run persistent trade deficits - by importing more than it sold.

But ask yourself this: why should foreign businesses and governments accept endlessly printable paper, with no intrinsic value, from the U.S. government? It is a risky proposition. So, quite rationally, they’ve converted that paper into dollar denominated hard assets - typically stocks and Treasury bonds. That flood of foreign capital flowed straight back into U.S. markets.

The result? A very skewed market with arguably over inflated valuations. Today, the U.S. stock market valuation represents over 70% of the MSCI World Index, even though its economy makes up only 26% of global GDP. No other country in history has ever commanded such a massive share of global market capitalization.

But that dominance may not last. Today, President Trump’s tariffs and a broader shift toward economic nationalism, the tide of globalization is starting to recede. Less trade means fewer dollars circulating globally - and less need for foreign nations to hold vast reserves of them.

So what happens if overseas investors begin to pull their money out of U.S. assets? If the U.S. stock market deflates from its current 70% share of global value, what happens to the valuations of individual companies - especially those high-fliers that have soaked up the lion’s share of foreign capital? (Yes, some of the Magnificent Seven, I’m talking about you.)

It brings to mind Japan in 1989, when its stock market accounted for half the world’s total. Today, it’s just 5.2%. So yes, there is precedent for large-scale corrections.

And yet, despite all of this, there’s a counterargument—a strong one—that the S&P 500 could still climb significantly higher from here.

As treasury inventories are reduced by foreign players, selling those bonds exerts more downward pressure on bond prices - driving interest rates still higher.

Meanwhile, U.S. National Debt stands at $37 trillion, which is an eye-watering, unprecedented 123% of GDP. It is the result of lax monetary policy since the GFC, exacerbated by the pandemic. The U.S. is running a budget deficit of $2.1 trillion or 7.3% of GDP, with interest expenses of $1.1 trillion - yes, you read that correctly, the U.S. pays away over one trillion dollars in interest annually. This exceeds total defense spending. It also exceeds the GDP of countries including Saudi Arabia, Switzerland, Poland and Argentina. This has never happened before and as rates creep higher, so too does the cost of that debt which becomes increasingly difficult to fund.

This explains why the U.S. has lost its triple-A credit rating from all three major rating agencies.

Spending cuts and a period of austerity might be the best medicine, but the current U.S. administration is moving in the opposite direction. Donald Trump’s “Big Beautiful Bill” will increase spending while concurrently cutting taxes - neither is helpful in resolving the current situation.

What about D.O.G.E.? It doesn’t even move the needle. It is on target to make a $0.5 trillion saving over the next four years, so $0.125 trillion per year against a national debt that looks like climbing from $37 to $40 trillion.

So the pressure is building in the system and something has to give. When the pressure becomes too great and debt default is not an option, the only lever left for currency-issuing governments is to expand the money supply.

In 2011 interview on NBC’s Meet the Press, former Fed Chair Alan Greenspan stated: “The United States can pay any debt it has because we can always print money to do that. So, there is zero probability of default.”

This looks like being the Trump plan. Printing money devalues the currency - great for those with high levels of debt, but it fuels inflation. It’s a playbook as old as fiat itself - and one investors ignore at their peril.

High inflation results in the bond market demanding higher returns on the debt it supplies - another reason to anticipate higher rates in future.

So while governments can promise to repay their debts, what they can’t promise is the purchasing power of the currency they use to do it. And that distinction matters -because getting your money back isn't the same as getting your value back.

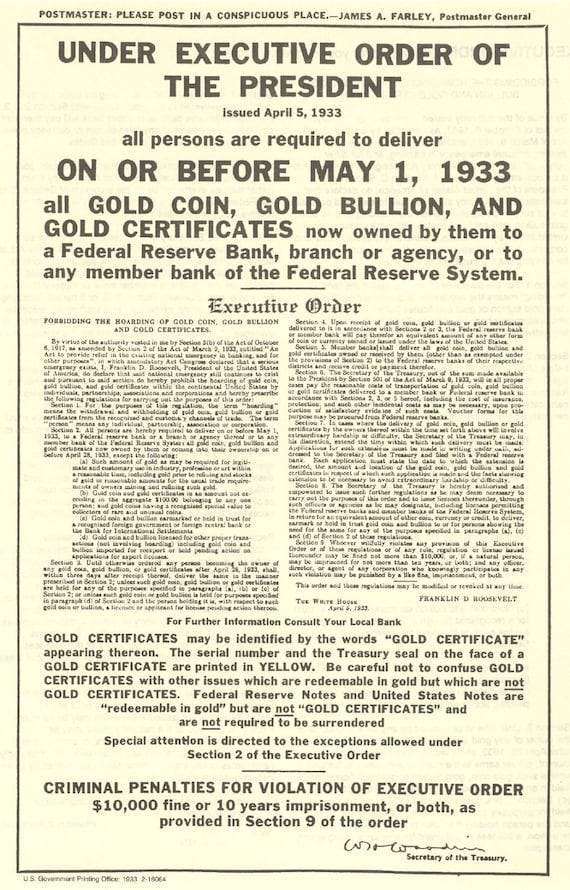

This certainly rhymes with something that happened back in 1933, which has a bearing on the value of gold today. Let’s delve deeper.

The Golden Dollar Story

In 1933, facing economic turmoil during the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt took the United States off the gold standard domestically and made private gold ownership illegal. Citizens were required to hand over their gold to the government in exchange for paper dollars, while the official gold price was revalued upward from $20 to $35 per ounce - gold's price in dollar terms increased by about 70% and the dollar’s purchasing power in gold terms dropped by 41%.

Consider that for a moment.

Ask yourself, ‘What is a dollar bill?’

At its core, money is simply a credit note - an earned promise you can use to buy goods and services with a central bank guarantee.

So imagine how Americans must have felt when they were forced to hand over their gold in exchange for these credit notes, only to later discover that those same notes would buy back just a fraction of the gold they had surrendered. In almost any other setting, this kind of exchange would be seen as blatantly fraudulent. U.S. Presidents using Executive Orders to engage in morally questionable behaviour is nothing new.

So why did Roosevelt do it?

This move allowed the government to expand the money supply and stimulate the economy, while simultaneously building up vast gold reserves. By the late 1940s, U.S. gold holdings had surged to over 22,000 tonnes, much of it acquired not just domestically but also from European nations seeking safe storage during World War II.

These immense reserves formed the foundation of the Bretton Woods system established in 1944, where 44 Allied nations agreed to a monetary framework that pegged all major currencies to the U.S. dollar, which in turn was convertible to gold at $35 per ounce. In effect, the dollar became the world’s reserve currency, and gold the anchor behind it.

This arrangement granted the U.S. extraordinary financial influence but also created a structural imbalance: while the rest of the world needed dollars to participate in global trade, only the U.S. could issue them. As America’s post-war spending soared - on foreign aid, welfare programs, and military ventures - doubts grew about whether it could truly back all those dollars with gold.

The imbalance intensified throughout the 1960s, with inflation rising, causing U.S. gold reserves to steadily shrink as countries began redeeming their dollars for gold.

The system reached a breaking point when French President Charles de Gaulle openly challenged U.S. dominance by demanding gold in exchange for France’s dollar holdings - going so far as to send battleships to New York to collect it. De Gaulle saw the dollar’s privileged role as unsustainable, calling it an “exorbitant privilege.”

Other nations followed suit, and gold hemorrhaged from U.S. vaults. In fact, figures like Peter Beter alleged Fort Knox had been emptied.

By 1971, the strain became untenable. President Richard Nixon suspended the dollar’s convertibility into gold, effectively ending the Bretton Woods system. This marked the beginning of the modern era of fiat currency - money backed not by metal but by trust. It was a turning point that reshaped global finance. It also explains why gold has an enduring role as a hedge against monetary instability and inflation.

As to the allegation about Fort Knox being emptied, and the United States possessing far less gold than the officially stated 8,133 tonnes - no one knows the truth. Today, the U.S. claims its gold sits safely in Fort Knox, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and a few mint facilities. But there hasn’t been a comprehensive, independent audit since 1953. Recent internal checks are opaque at best, and doubts linger - about both the quantity and the quality of the gold. If it's mostly 1930s-era "coinmelt" bars, much of it may not meet modern purity standards. Officials like Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent insist it’s all accounted for, but until there’s a full, transparent audit, suspicion will remain. Trump and Musk have floated the idea of a livestreamed audit - perhaps even jokingly - but the fact that it’s even being discussed seriously signals something has shifted. A proper audit would clear the air - or set off a shockwave. Either way, the time for speculation is running out.

Markets, for now, seem calm, with central banks, particularly in Asia, quietly hoarding more gold. China certainly owns far more gold than it publicly claims. However, without knowing the true extent of global gold reserves, pricing it becomes inherently tricky.

What Does This Mean For Investors?

Simply holding cash is a losing proposition, as inflation steadily chips away at its purchasing power.

Putting that cash into bonds doesn’t offer much relief either - rising interest rates mean falling bond prices, which is a double edged sword - you are either locking your money into a sub-optimal interest rate for a term or else you could sell the devalued bonds and suffer capital losses.

That leaves hard assets like gold, which have historically provided a hedge against inflation. However, as explained, gold is difficult to properly value in addition to which, while gold protects purchasing power, it doesn’t generate income or compound wealth. To make real gains on non-productive assets you need to buy them when they are cheap and given gold’s recent rally, that window may have already closed.

There are other corners of the commodity market worth exploring. Just last week, I highlighted an opportunity in the platinum group metals - an area with strong fundamentals and an asymmetric upside skew.

Some readers will be screaming ‘Bitcoin!’ - but hold that thought for a moment and I’ll come back to it shortly.

What About Equities and Bitcoin?

As explained at the outset of this post, investing in companies is another great hedge against inflation. As costs rise, so too do prices, revenues and earnings. This buoys the value of the business.

This is how to think about it: companies invest in growth with today’s money, but collect revenue with tomorrow’s inflated currency. That boosts returns on investment during inflationary times.

“Whenever you can buy a large amount of future earning power for a low price, you have made a good investment”

Sir John Templeton

Not only that, but economic goodwill doesn’t erode in value - just think about the Coca Cola brand name for example - it requires no maintenance CAPEX and it earns an ever increasing number of tomorrow’s dollars on the sale of its products.

The same is true for companies with real assets that don’t erode in value.

However, this only works for companies with pricing power and wide margins. Why? Narrow margins imply high input costs and if those increase with inflation, then much of the benefit is eroded. Worse, if the company operates in a commoditized industry with little or no pricing power, it may find that its costs rise more quickly than its revenues.

So selecting the right companies becomes more important than ever.

Focus on the balance sheet is equally important. Over leveraged businesses are likely to be hit hard by higher rates in an inflationary environment.

So investing in equities looks like a good bet as inflation will push valuations higher - but investors need to be more selective than ever.

I believe we’re entering a new chapter that requires a different approach. Passive investing is likely to be far less effective in the next 5 years than it was looking backwards.

The market darlings of the past decade - names like Apple and Tesla - may struggle to repeat their outperformance, particularly since their valuations had already run ahead of intrinsic value and their unit economics seem to be deteriorating - a situation that isn’t helped by international trade wars.

Similarly, tech companies that used to prioritize customer acquisition over profitability and so burned through endless amounts of cheap capital will struggle with that strategy as the cost of capital rises. They’ll be forced to adapt or else they’ll falter.

So it appears that we're returning to a more discerning market, one where fundamentals matter again. Stock picking is making a comeback. Investors will need to be more selective, with a renewed focus on quality, resilience, and value. In this environment, active investing may finally reclaim its edge over the passive strategies that have dominated in recent years.

So, what about Bitcoin?

Here’s how I think about it. When I invest, I look for a few key qualities - durability, predictability, resilience, scalability, and an ethical alignment with how I believe capital should function in the world. And when I put Bitcoin through that lens, it just doesn’t stack up - here are my 6 reasons:

First, longevity. I want to own assets that will still be relevant and thriving ten, twenty, even fifty years from now. Take Coca-Cola - it's been around for 150 years and probably has another 150 to go. That’s the Lindy effect: the longer something survives, the longer it’s likely to keep surviving. I also ask myself: what happens if this thing just disappears? Imagine if Microsoft vanished overnight. No Windows, no Office. It would cause chaos. Businesses around the world would grind to a halt. That’s what staying power looks like.

But what if Bitcoin vanished tomorrow? A few speculators might lose money, but beyond that… life would go on unchanged and nobody would notice.

Next is predictability. I want assets that generate reliable, measurable returns. A business with growing profitability or a property collecting rent - this gives the asset intrinsic value.

Bitcoin doesn’t generate returns and any notion of a “Bitcoin yield” is pure fiction - snake oil for the digital age (see ‘the fiction of Bitcoin yield’ here).

Then there’s resilience. The kind that lets an asset withstand recessions, downturns, and shocks to the system. Strong companies pivot, tighten spending and are able to tap in to diverse revenue streams. That’s how they protect investor capital.

Bitcoin? It behaves more like an active volcano - dormant one minute, explosive the next. The highs can be spectacular, but the drops are just as severe. It’s a thrilling ride, not a long-term wealth engine.

I also look for economic sustainability and scalability. The best businesses throw off so much free cash flow they can grow organically without raising new capital. They fuel their own fly-wheel. You don’t need to watch a share price to know they’re getting stronger. If revenue grows 9% a year, the company doubles in size in about six years and with operating leverage, earnings may grow even faster. That’s compounding in action

Even if the market shut down for a decade, I’d be fine. Earnings from good businesses will increase, rent on real estate will increase and my investments would quietly gain value even in an absence of buying or selling.

Bitcoin, though, is a different story. It has no organic growth engine. It doesn’t create any value - no earnings, no rent, no output. Its value is entirely based on what someone else is willing to pay. If the market says $100,000, then that’s the price. If enthusiasm sends it to $1 million - which I accept may happen - then that becomes its new price tag for the time being. If people stop ascribing value to it, it becomes worthless. It is all about flows of money propping up the price - as long as the money continues to flow, it has a value. So unlike equities or real estate, without buyers to assign it a price, its value completely disappears.

But to me, anything that exists only because there’s a market for it is just a fantasy. It’s not value creation, it’s just an illusion. A zero-sum game where wealth is simply transferred, not built. That’s why it’s so unstable. It’s not just volatile, it’s inherently volatile. The price is sentiment-driven. And when confidence evaporates, so does liquidity. Bitcoin has already crashed by over 50% more than four times. Real wealth doesn’t behave like that.

Then there’s the ideology. Bitcoin has developed a kind of cult following, driven by a libertarian dream of "opting out" of the mainstream financial system. It’s rooted in a belief that Bitcoin offers freedom from government control, censorship, and centralized authority. It is especially popular among those who distrust governments and believe large financial institutions have too much power. This sentiment is often reflected in crypto culture, where terms like "HODL" and "diamond hands" signal a commitment to holding on through volatility as a form of resistance.

While this narrative began with a small rebellious and possibly disenfranchised group, it has slowly gained in popularity as Bitcoin ownership has increased - even among traditional capitalists. It raises an interesting question: do they really believe the hype, or do they simply espouse it in the hope of pumping the value of their Bitcoin holding? I’ll leave you to decide!

The Bitcoin cult seems to ignore the inconvenient truth that its extreme ‘value’ volatility prevents it from becoming a reliable medium of exchange or a stable store of value. It can’t be used in business contracts, for paying wages or for taking out loans. This means that it is entirely dependent on fiat currency as a measure of its value from time to time - kind of ironic - so much for displacing fiat currency!

More particularly, the appeal of Bitcoin seems to be rooted in its volatility - just like a lottery ticket, it may land its owner a huge windfall. So the Bitcoin cult would probably disappear if ever it stabilized in value creating something of a paradox. For now it is nothing more than a zero-sum game: wealth transfer driven by speculation - that’s not a game I’m interested in playing.

Last, but by no means least, there’s also an ethical dimension. Capitalism, at its best, directs capital toward its most productive uses. It enables innovation (Schumpeter’s creative destruction), specialization (Smithian economics), and progress. It has undoubtedly lifted living standards and driven prosperity.

The crypto currency market doesn’t do that. It locks away $3.5 trillions dollars in idle speculation. That’s trillions of dollars sitting idle - producing nothing, building nothing, helping no one. Imagine if that capital were redirected into businesses that innovate, infrastructure that serves society, or even debt that helps fund governments in need. The economic boost would be enormous.

Even worse, it creates societal vulnerabilities. It’s been linked to tax evasion, terrorist financing, drug trafficking, ransomware, and helping rogue states sidestep sanctions. Why would I want to support that?

So it’s not just about where we’re putting our money, but what that money is doing while it’s there. Something worth thinking about for anyone holding crypto.

I know some of you will disagree with me, and I respect that. But as for me - I’ll stick with the stock market.

What do you think? Post your comments below.

Thanks James - I enjoyed the article. You summed up my thoughts on Bitcoin better than anything I've read. Regarding the S&P comparison to gold, I think if you factor in reinvested dividends the outcome changes quite significantly. Assuming a 2% annual dividend reinvested over the 55 years the S&P index might be around 17,000. Anyway, thanks again.

This article seems to align with my sentiments https://open.substack.com/pub/renesellmann/p/free-everything-you-thought-was-safe?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=1owuoe

It's well worth a read. When many thinkers seem to be calling out the same thing, it certainly adds weight to the argument.